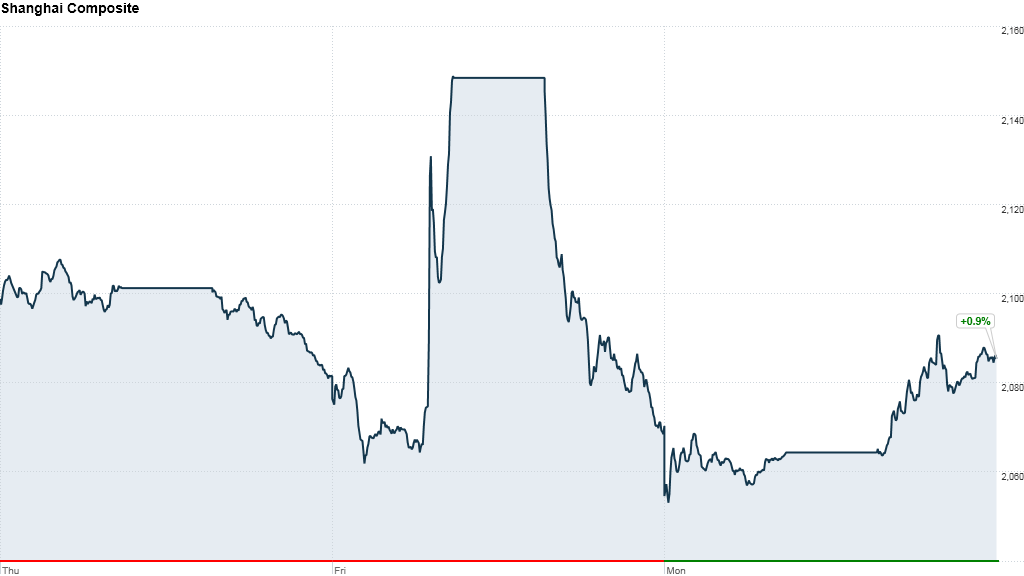

China's top stock market has been shaken in recent days by a series of fat-finger trades that have damaged investor confidence and raised questions over how the market is regulated.

The trades, which included more than 23 billion yuan in mistaken buy orders, have been traced to state-backed brokerage firm China Everbright Securities.

The company's president resigned on Thursday, regulators have opened an investigation and the firm has been barred from trading on its own account.

Other markets have suffered similar flash moves. But government regulators have described the Everbright trades, which quickly created and then erased billions in value, as the biggest snafu in the market's history. The investigation has now been expanded to include other companies that use high-frequency trading platforms.

While the Everbright trades may prove to be an isolated incident, the episode underscores what analysts say is a need for more effective regulation and greater transparency in Shanghai. Even while China's economy has raced ahead in recent years, retail investors have taken their money out of stocks and the market has lagged its international rivals.

Wendy Liu, Nomura's head of China equity research, said that at the moment, the Shanghai market is "a very muddy pool of water." Retail investors, she said, simply "don't want to go there."

Data show that individual investors have abandoned stocks in droves and are instead seeking out higher returns in alternative investments.

In 2005, retail investors held about 70% of the mainland's total market cap with large financial institutions holding the rest. But that breakdown steadily reversed, and individuals' investments represented only 27% of the market by 2011, according to Nomura's compilation of government data.

Among the top alternatives are physical property, wealth management and trust products that tend to offer more lucrative returns. Anecdotal evidence suggests retail investors are also diverting funds to underground lending outlets and foreign real estate.

The flight of retail investors has taken a toll on the benchmark Shanghai Composite Index, which is down 9% so far this year and 14% since 2008.

"You want this to be an asset that Main Street -- not just Wall Street -- is more enthusiastic about getting involved in," Liu said.

Related story: China's underdog market surges

Liu said that better regulation starts with more stringent requirements for public companies. For example, troubled companies are hardly ever taken off the market in Shanghai, and firms use all kinds of schemes to stay listed.

Nomura data shows the China market has de-listed only 4% of companies since 2003, compared to 60% in the U.S. and 15% in Hong Kong over the same time period.

If progress is to be made, regulators must be more strict, Liu said.

Modernizing the Shanghai market will also mean diversifying financial product offerings, said Z-Ben Advisors analyst Winnie Deng.

Regulators have made some progress on this front, encouraging the creation of alternative investment options such as exchange-traded funds, mutual funds or other bundled securities.

Related story: Dream companies for Asia's grads

At the same time, Liu warned that creating increasingly risky financial instruments could spell trouble for the relatively young and inexperienced industry.

"They're coming out of the same pool," she said. "If the bunch is bad, there are only so many ways you can cut it."

Yet it may not remain all doom and gloom for mainland stocks.

The Shanghai Composite has been on an upswing, and if the world's second-largest economy is able to reach its own target of 7.5% full year GDP growth, stocks may extend their winning streak.