Lawmakers are tied up in knots over increasing the debt ceiling this fall. But they eventually will. The only question is how messy the process will be.

Why assume they'll raise it? Because they have no real choice if they want to avoid a U.S. default. A default would hurt the economy and markets, and most lawmakers know this. That's why they regularly raise the debt ceiling before it comes to that.

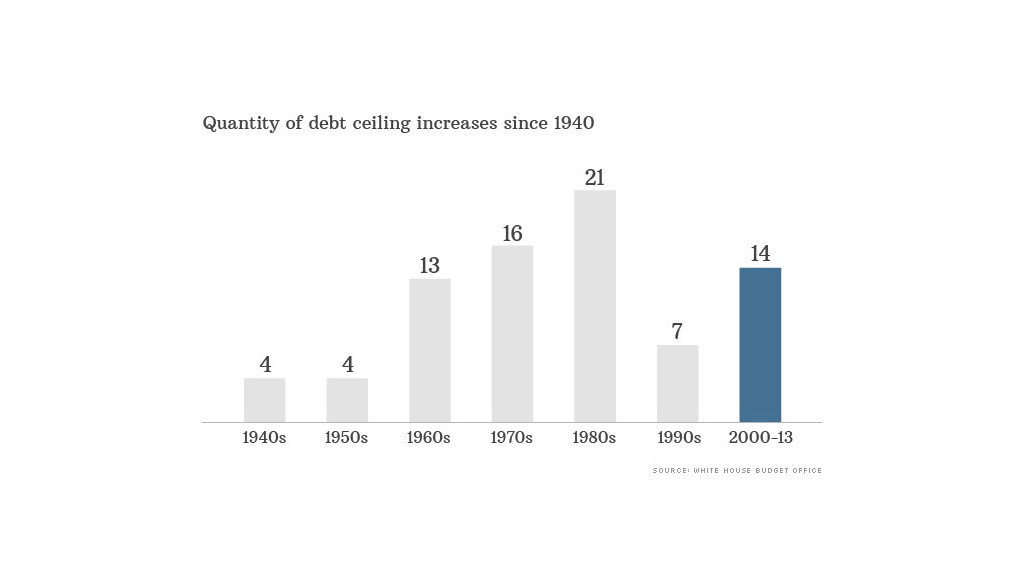

In fact, since 1940, Congress has effectively approved 79 increases to the debt ceiling. That's an average of more than one a year.

How do they raise it? Sometimes lawmakers have raised it by small amounts, other times by large amounts. And sometimes they've raised it "temporarily" with provisions for a "snap-back" to a lower level.

Since it's a politically tough vote, they occasionally devise clever ways to tacitly approve increases without ever having to publicly record a "yes" vote.

For example, as part of the deal to resolve the 2011 debt ceiling war, Congress approved a plan that let President Obama raise the debt limit three times unless both the House and Senate passed a "joint resolution of disapproval." Such a measure never materialized. And even if it had, the president could have vetoed it.

Then this past February, lawmakers decided to temporarily "suspend" the debt ceiling.

Under this scheme, Treasury was able to continue borrowing to pay the country's bills until May 19. At that point, the debt limit automatically reset to the old cap plus whatever Treasury borrowed during the suspension period.

Related: Debt ceiling 'X' date could hit Oct. 18

What does raising the debt ceiling accomplish? Despite some politicians' incorrect assertions, raising the debt ceiling does not give the government a "license to spend more."

It simply lets Treasury borrow the money it needs to pay all U.S. bills in full and on time. Those bills are for services already performed and entitlement benefits already approved by Congress. In other words, it's a license to pay the bills the country incurs as a result of past decisions made by lawmakers from both parties over the years.

Refusing to raise the debt ceiling is "not like cutting up your credit cards. It's like cutting up your credit card bills," said historian Joseph Thorndike, who has written about past debt crises.

How high is it today? The debt ceiling was reset at $16.699 trillion on May 19, up from the $16.394 trillion where it was before the suspension.

Since then, Treasury has been forced to use "extraordinary measures" to keep the country from breaching the limit.

Treasury Secretary Jack Lew said those measures will be exhausted by mid-October, after which he will only have $50 billion on hand, plus incoming revenue to pay what's owed. Sounds like a lot, but it won't last long.

How long will it last? An analysis by the Bipartisan Policy Center estimates that the Treasury will no longer be able to pay all bills in full and on time at some point between Oct. 18 and Nov. 5.

So, you're saying they only have a few weeks to work this out? Yup.

House Republicans say they will demand spending cuts and fiscal reforms in exchange for their support of a debt ceiling increase. The White House, meanwhile, has said it won't negotiate quid pro quos.

The question is when will Republicans or the White House -- or both - bend in the standoff? If recent history is any guide it likely will be just in the nick of time.

And there's no telling how creative the deal they cut will be.

But any bad blood created along the way almost certainly would poison other budget negotiations.