Experts agree: A federal government shutdown would be a dumb way to go.

Yet the risk of a shutdown on Oct. 1 is now a distinct possibility. And federal agencies have been instructed to make plans for one just in case.

The House on Friday will vote on a short-term government funding bill that will include a provision to defund Obamacare. That provision is a no-go for Senate Democrats and President Obama.

If they can't work out a compromise, many functions of the federal government will be shut down indefinitely on Oct. 1.

Besides causing inconvenience and delays, a shutdown could have larger consequences.

A long, broad shutdown could weaken an already modest economic recovery, Congressional Budget Office Director Douglas Elmendorf said Wednesday.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, meanwhile, noted that "a government shutdown and, perhaps even more so, a failure to raise the debt limit could have very serious consequences for the financial markets and for the economy."

To say nothing of the fact that a shutdown wouldn't come cheap. Federal agencies have to use up time, energy and resources to plan for one. Shutting down, and then reopening the government, also costs money. Two shutdowns in the mid-1990s cost an estimated $1.4 billion, according to the Congressional Research Service.

There's no telling exactly what a shutdown this October would look like because the White House has some discretion in terms of what's hit and what's not. But based on the shutdowns in the mid-1990s, the following is a pretty good bet.

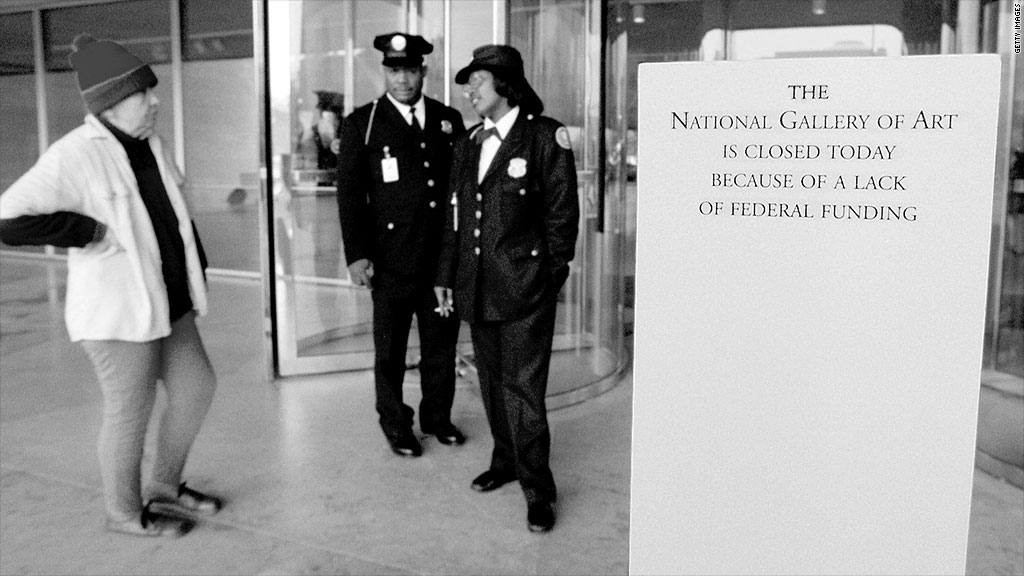

What will be closed for business: Many, if not most, federal government offices, programs, museums and parks would be shuttered.

So if the shutdown lasts awhile, the travel industry could take a hit as vacations and business trips are scuttled -- whether because people can't get a visa or passport or because they have to cancel their plans to visit Yosemite.

For federal contractors, projects may be delayed because the agencies they work for can't issue the paperwork needed to move forward.

And Americans who need something from a federal office affected by the shutdown may be out of luck.

What will be open for business: Parts of the government that provide what the White House budget office deems critical would still operate.

Critical services, broadly speaking, protect human life and property. Typically that has included air traffic control, national security, the handling of hazardous waste, food inspections, border protection, maintenance of the power grid and disaster assistance.

In addition, taxes likely would still be collected, and U.S. bonds issued. Anything else deemed essential to the preservation of the country's banking system would likely carry on as well.

Related: Pessimism deepens over budget standoff

Who will come to work and who won't: Hundreds of thousands of federal workers would be furloughed without pay. Historically that pay has been restored when the shutdown ends, but there's no guarantee of that in law.

Many federal employees, however, would be exempted from furloughs. President Obama and his presidential appointees, as well as members of Congress, fall into that category.

Also expected to work through a shutdown are federal employees needed to preserve key parts of the money and banking systems.

Anyone authorized to work during a shutdown would be paid, although in most instances they will not get their checks until after the shutdown ends.

How mail would be affected: The mail would still be delivered.

How justice will be served: The federal judiciary estimated that if a shutdown had occurred this year, the court system could have functioned for roughly 10 working days on the basis of fees and funds from prior appropriations, according to CRS.

Related: Budget follies: 3 crazy years and counting

When that funding runs out, the judiciary would allow "essential work" to be performed, including the resolution of cases.

Federal court staff and officers who work through the shutdown would not be paid during the shutdown. But Supreme Court justices and federal judges appointed under Article III of the Constitution would.

If you're called for federal jury duty, you won't get paid for it on time.

What happens to Social Security and other benefits: Funding for entitlement benefits is considered mandatory, meaning it's not subject to the annual appropriations process.

So the money will be there to pay the benefits. The only question is whether the federal workers who process them will be.

Social Security checks did go out during the last shutdown, and the White House should be able to ensure the same thing happens again if need be.

During the mid-1990s shutdowns, the Social Security Administration initially retained nearly 5,000 employees to send benefits to those already enrolled in the program. But during the second, longer shutdown, it realized it would need closer to 50,000 employees to process applications for new claims or Social Security cards, address changes and other benefit-related tasks.

How Obamacare will fare: Those who would threaten to shut the government down are those who most want to see Obamacare delayed and defunded.

But an analysis by the CRS concludes that the implementation of Obamacare is likely to continue in the event of a shutdown.