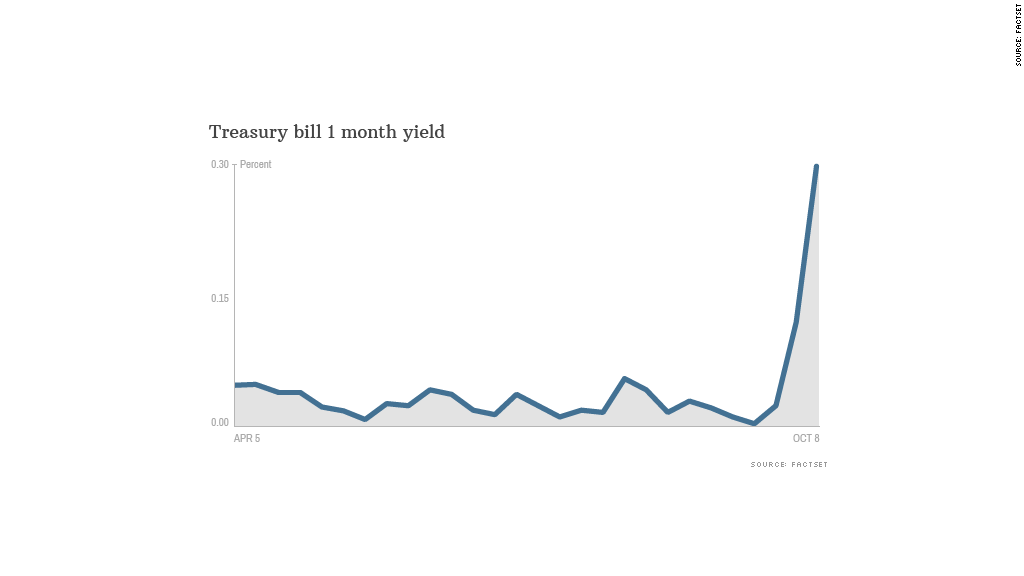

Fears of a debt ceiling breach surfaced Tuesday in the market for U.S. debt, with the yield on one-month Treasury bills surging to its highest level since the financial crisis.

Investors aren't concerned about the country's long-term ability to pay its debts -- the yield on 10-year bonds has actually fallen in the past few weeks. But the question of whether a debt-ceiling breach will hold up repayments in just a few weeks' time is another matter.

At an auction Tuesday, the government sold $30 billion worth of T-bills maturing Nov. 7 at a rate of 0.355%, nearly triple the rate of the auction a week prior. Yields move inversely with the price of the debt.

T-bills are typically used by buyers such as money market funds as a risk-free means of stashing cash for short periods of time. Those funds need to make sure they've got cash on hand if investors want to make withdrawals.

"Even though we all believe that this default won't happen, as we get closer and closer without any progress, we have to wonder," said David Coard, head of fixed-income trading at Williams Capital Group.

"What you're seeing with some money funds is concern about redemptions, and when that develops, it generally means that they're going to build up their cash," Coard said. "What that does is make the short-term funding markets more challenged."