Food prices are on the rise. You're likely paying more for products like beans, wheat bread, tomatoes and mayonnaise.

You won't hear that in the government inflation report, which was delayed because of the government shutdown.

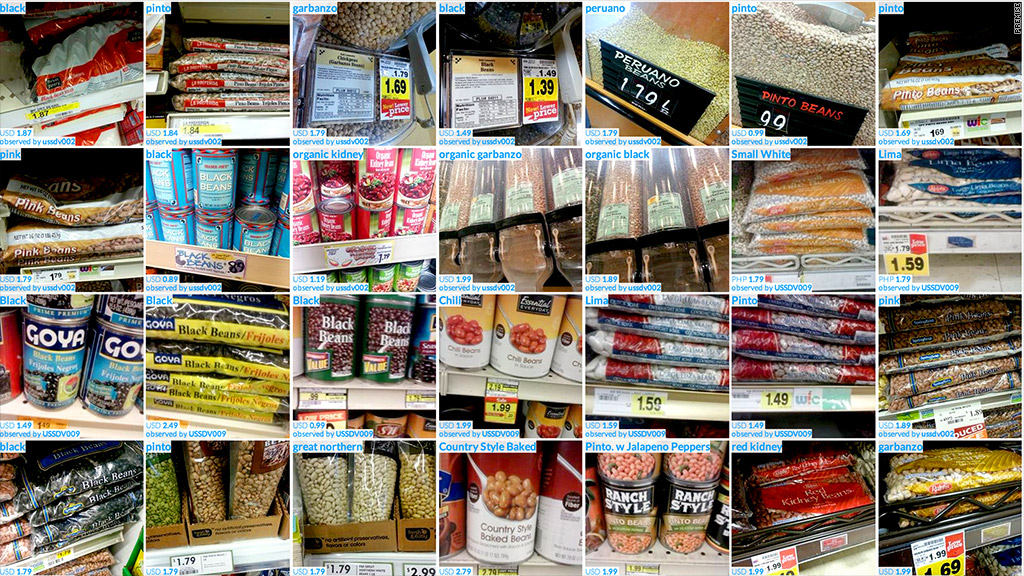

But an alternative index released Tuesday from San Francisco-based start up, Premise, uses image snapshots to build an even more comprehensive set of data to track prices.

The company aims to provide up-to-the-minute price information on thousands of food and other consumer products worldwide, using images captured from online retailers, and individual cell phone cameras of store shelves, to gather real-time data on prices.

The site strives to combine Big Data analytics with mobile technology to fill a crucial void -- the time between now and a month ago, when most survey-based data -- such as the U.S. government's Consumer Price Index -- is from.

While consumers may not be planning their weekly shopping list around it, anyone from governments making monetary policy decisions to traders looking to get ahead of such moves may be interested in real-time inflation data.

"If you're relying on the old infrastructure, you're literally months late," said David Soloff, the company's co-founder and CEO. "We can capture data at a much greater scale, much more quickly and cheaply."

The company has some big name backers, including Google and Andreessen Horowitz. And they've brought on well-known advisers like Google (GOOG) Chief Economist Hal Varian and former White House economist Alan Krueger.

Related: Seniors to get small Social Security increase in 2014

Premise's numbers show food prices in the U.S. rising -- 0.2% in September verses 0.1% the month prior.

For its U.S. food index, Premise relied on 240,000 different data points, compared to the 5,000 or so typically used for the government's CPI report.

Most of the company's U.S. numbers currently come from scouring the web sites of online retailers. In the developing world, where there's less e-commerce available, Premise has a team of 700 contractors that go from store to store in 25 countries, snapping photos of products and prices on smart phones and sending it back to the company for analysis. The going pay is between 12 and 25 cents a shot.

Premise plans on using more mobile phone collection in the United States as well, as its customers are also interested in seeing the quality and availability of the products.

Premise's founders hope the real-time inflation data could become a game changer in the world economy.

One example: food riots in India. Over the summer the price of onions in India -- a crucial cooking ingredient -- rose 300%, sparking riots across the country. Soloff said Premise researchers picked up on the price rise some three weeks before the rioting broke out.

Peter Klenow, a Stanford economist who studies inflation, said the usefulness of real-time data collection largely depends on how wide of a net a company casts when pricing products. Also, there's some question as to whether online prices are the ones paid by typical consumers.

Still, Klenow said the data could be especially useful to government policy makers trying to get a handle on what's happening in the economy.

"They are always looking for leading indicators," he said. "And a lack of data is a big constraint."