Just because we spend a lot of time in school doesn't mean we're smart.

American adult proficiency in literacy, numeracy and problem solving ranks as some of the lowest among developed countries, despite a relatively high level of education, according to a recent survey.

In literacy, the United States came in 9th out of 13 industrialized countries surveyed, according to a report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

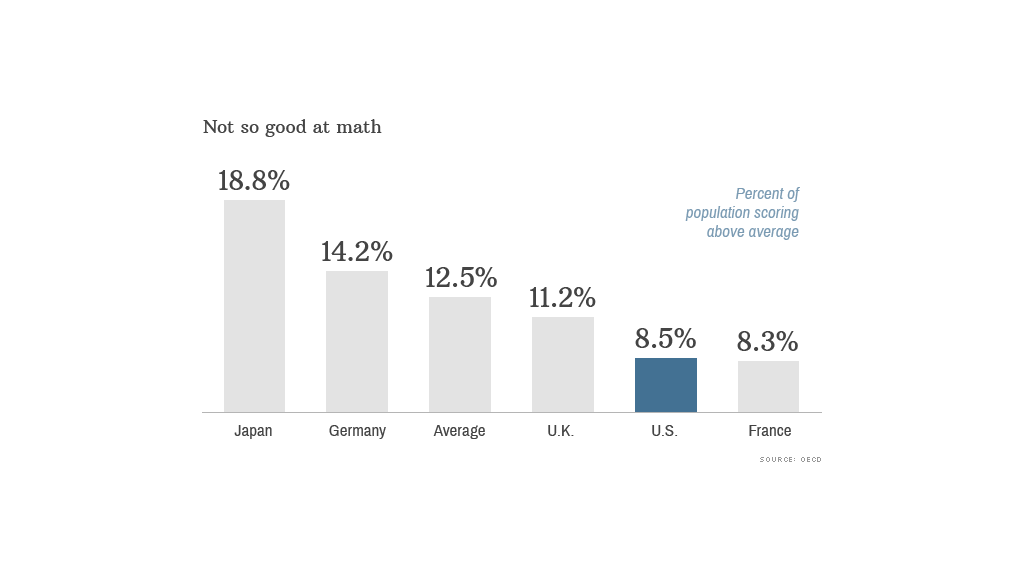

In problem solving America ranked 8th, right below average. And Americans are particularly bad at math, coming in third from last in the numeracy rankings.

"It's distressing to see we are not performing well," said Mary Alice McCarthy, a senior policy analyst at the New America Foundation. "Young people are moving into adulthood and they do not have the necessary skills."

This comes despite the fact that the number of years Americans are expected to spend in school -- 17.1 -- is just below the OECD average of 17.5 years, and above the 16.6 years expected in the U.K. and the 16.2 years in Japan.

Related: Why young people are saying 'no' to the workforce

McCarthy said one thing that was particularly problematic is that young people in the United States are not showing a much higher level of skill than older people, despite the fact that the jobs of tomorrow will require a greater degree of knowledge.

The report attempted to measure the reading, math and problem solving skills in real world situations of over 5,000 Americans between the ages of 16 and 65.

It noted that a lack of these skills translated into real life hardships, and they were especially pronounced in America. In the United States, the odds of being in poor health are four times greater for low-skilled adults than for those with the highest proficiency -- double the average of other countries in the study.

One of the reasons America may not have scored so high is immigration, said William Thorn, a senior analyst in the education division at OECD. Immigrants tend to have fewer skills, and can bring down the average.

As with income inequality, the skills disparity was also high in the United States, said Thorn, with a big discrepancy between the good and poor performers.

Yet having a high skill set doesn't necessarily translate into a more productive economy or greater economic output. After all, Japan topped the list in both reading and math yet hardly has a red hot economy.

"The skills of a population are not entirely summarized by literacy, numbers and problem solving," said Thorn.

Still, if we want to right the situation, grades K-12 seem to be the place to start -- American college students tended to have skills more on par with their international peers.

There's no shortage of ideas on how to make America's schools better. Sandra Stotsky, a retired education professor at the University of Arkansas' Department of Education Reform, thinks students need to be held more accountable. There needs to be less testing throughout the year, but more high-stakes testing at crucial times. If students don't pass the test, they don't move on to the next grade.

Stotsky also thinks students need more options to go into the trades in high school instead of a relentless focus on sending kids to college, especially when they are not prepared.

Finally, a greater cultural emphasis on reading would do wonders, Stotsky said.

"Our students spend an enormous amount of time watching TV and playing video games," she said. "How can we expect high levels of literacy from people who don't read?"

Other ways to boost the U.S. skill set include greater access to early childhood education and more adult education programs targeting low-skilled workers, said New America's McCarthy.