Alarm bells are ringing again over the health of the European economy, after a surprising fall in inflation last month.

With eurozone unemployment stuck at record levels above 12% and the economy failing to generate momentum after emerging from recession earlier this year, some analysts are warning that the region is at risk of sinking into a Japanese-style era of deflation and stagnation.

Such talk has led to calls for the European Central Bank to cut interest rates to a new record low when it meets Thursday, or at the latest in December, to inject new impetus into the weak recovery and take some of the heat out of a rally in the euro.

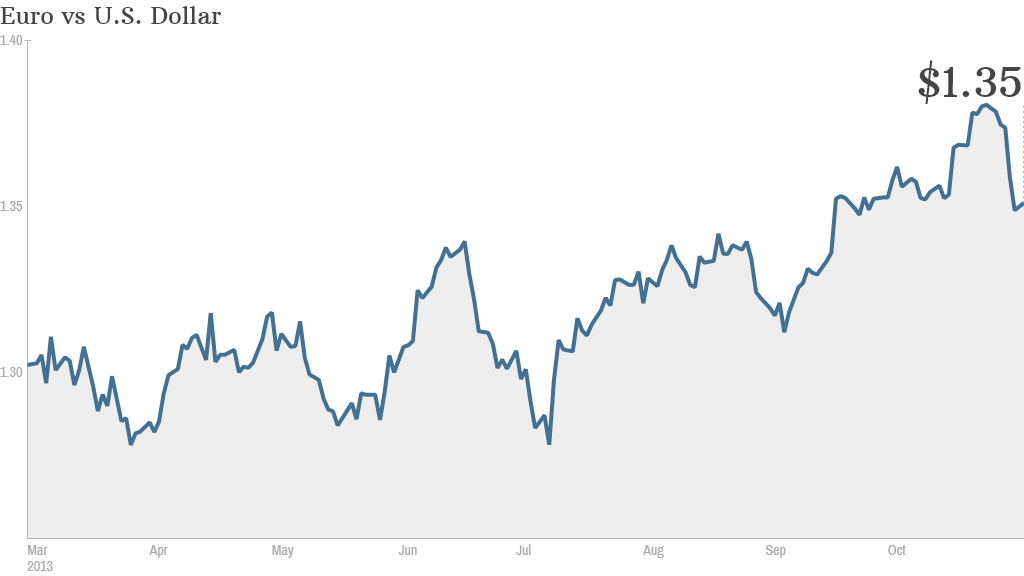

The currency hit a two-year high of $1.38 last week before falling back after the October inflation numbers.

But it's still up 5% since March -- boosted by the return to growth and expectations that the Fed will delay any tightening of U.S. monetary policy until 2014 -- and that makes it harder for struggling euro zone states such Italy, Spain and Portugal to export their way out of trouble.

Related: How sick are Europe's banks? Wait and see

Eurozone inflation fell to 0.7% in October, from 1.1% in September, with food prices and the cost of services coming under the most pressure. Over 19 million people are out of work in the euro zone, keeping a firm lid on wages and depressing domestic demand.

ECB President Mario Draghi said last month the bank stood ready to cut rates again to shore up the weak recovery. And the growing risk that inflation will undershoot the ECB's target of "below but close to 2%" by a wide margin for years to come could stir the bank into action this week.

"We believe that the October [inflation] reading of 0.7%, the rather broad-based nature of disinflation, and the firm euro will force the ECB... to shift towards a rate cut," wrote UBS economist Reinhard Cluse in a note, predicting a cut in the key ECB rate to 0.25%.

Related: Spain joins bumpy European recovery

Most economists, however, expect the ECB to use Thursday's meeting only to signal a rate cut in December, when it will have third quarter eurozone GDP data and its own updated growth and inflation forecasts for 2014 and 2015 to consider.

The U.S. criticized Germany last week for pursuing policies that resulted in a "deflationary bias" for the eurozone and wider global economy. In a semi-annual report, the Treasury Department called on Europe's largest economy to rely less on export growth and boost domestic demand.

Germany rejects any suggestion that its policies are damaging its neighbors.

Germany's trade surplus with its eurozone partners has fallen sharply over the past five years, and is now smaller than the surplus it generates with the rest of the world.