It's a very small deal. It's a bipartisan deal.

And it's a deal that -- if passed by the House and Senate -- will avert budget brinksmanship for the next year and a half and let lawmakers focus on other things for a change.

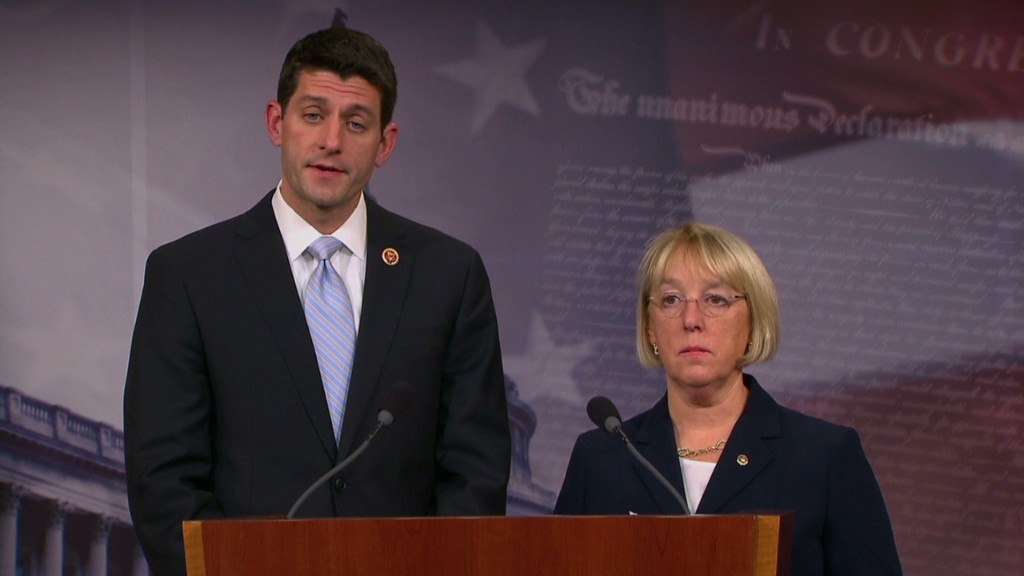

The budget deal announced by Senate Budget Chairman Patty Murray and House Budget Chairman Paul Ryan Tuesday evening would set federal spending on domestic and defense programs at a little more than $1 trillion for both this fiscal year and next.

It also would replace about $63 billion of the automatic budget cuts scheduled for 2014 and 2015, with the majority of the relief coming in the next 10 months. To match the savings from those cuts, the deal would raise new non-tax revenue through a host of measures, including higher airline passenger security fees and increased federal worker contributions to their pensions.

But here's what the deal doesn't do:

1. The sequester: It doesn't replace the so-called sequester for much of the rest of the decade. In fact, it actually leaves all of it in place for both defense and nondefense programs for 2016 through 2021 and even extends it for another two years after that for certain mandatory spending, including on Medicare.

2. Unemployment benefits: It doesn't extend emergency unemployment benefits for long-term jobless Americans. An estimated 1.3 million unemployed people will be cut off from federal jobless benefits by the end of the year. And another 850,000 could fall off the rolls within the first three months of 2014, according to the National Employment Law Project.

3. Medicare doctor payments: The deal doesn't address what both parties say they want to do: Figure out a way to prevent a big cut to Medicare physician pay. Come January 1, reimbursements to doctors who see Medicare patients are slated to be slashed by more than 24%. Unless, that is, Congress chooses to renew the so-called "doc fix," which averts scheduled cuts in doctor pay.

4. The long-term debt: It doesn't really move the needle much on the country's long-term debt trajectory. That's because Ryan and Murray opted for pragmatism, explicitly ruling out wrestling over entitlement and tax reform in this round of negotiations.

5. The debt ceiling: The deal would help Congress avert budget brinksmanship for awhile. But it does nothing to prevent another bruising battle over the debt ceiling, which lawmakers must address in just a few months.

The bargain lawmakers struck in October to end the federal government shutdown included a provision to suspend the nation's borrowing limit for a few months. It lets the Treasury Department continue borrowing new money through February 7 without regard to the debt limit. Then, on February 8, the debt limit will automatically reset to a higher level that reflects how much Treasury borrowed during the nearly 4-month suspension period.

At that point, if Congress hasn't agreed to raise the ceiling, Treasury can use "extraordinary measures," the special accounting maneuvers that let it keep paying the country's bills without going over the debt limit and risking default on the nation's obligations.

But those measures are expected to run out sometime between March and June, although Treasury Secretary Jack Lew has warned that based on where things stand now they are not likely to last more than about a month.