If there's one point Ben Bernanke wanted to hammer home on Wednesday, it's this: The Federal Reserve is still trying to stimulate the economy, even if that stimulus flows at a slightly slower pace.

"We're certainly not giving up," Bernanke said, minutes after the Fed announced it would start reducing the amount of bonds it buys each month -- a process Wall Street had called "tapering."

"While we are slowing asset purchases a bit, we expect the total balance sheet to be quite large and maintained at a large level for a long time," Bernanke added later.

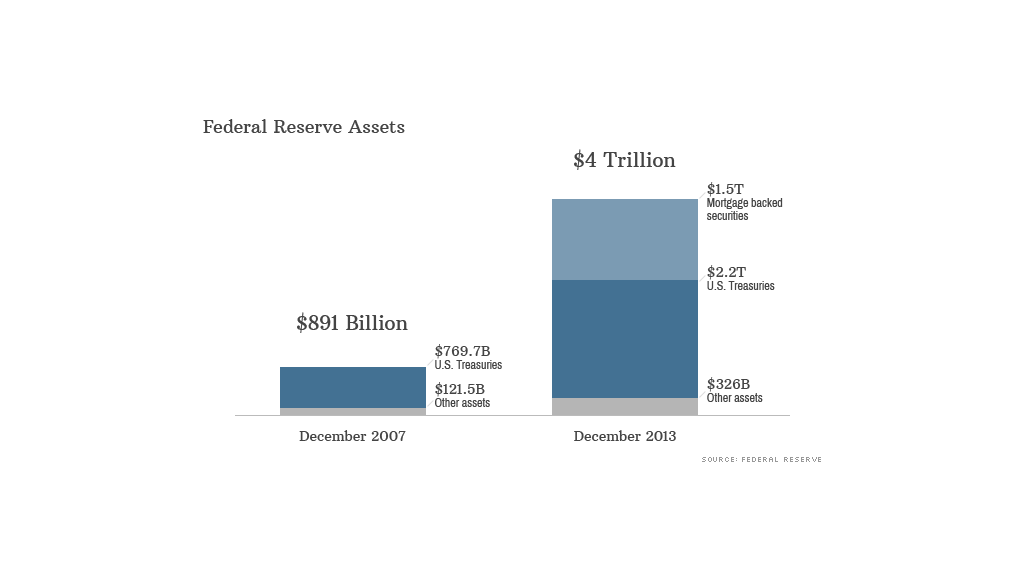

Tapering doesn't begin until January, and meanwhile the bond-buying continues at full strength. Just this week, the program pushed the Fed's portfolio over the $4 trillion mark.

To be more exact, the Fed's assets now total $4,008,062,000,000 -- a new record high, according to a weekly report released by the central bank on Thursday afternoon. And it's going to keep climbing.

Starting next month, the Fed plans to buy $75 billion in bonds, down from the $85 billion it has been buying every month since September of last year. If the economy progresses as hoped, they plan to continue gradually reducing the bond buys.

CNBC's Steve Liesman calculates that if the Fed makes a similar $10 billion cut at each of its meetings next year, the Fed's assets will climb to $4.6 trillion a year from now.

These numbers aren't remarkable for any other reason than they're just plain huge.

But if anything, the sheer magnitude of the figure is just one more sign of how deeply the economic crisis hurt the U.S. economy.

"The broader takeaway is, this is an illustration of how much monetary accommodation was needed to cushion the bursting of the housing and credit bubble," said Goldman Sachs Chief Economist Jan Hatzius. "It was a very painful and costly event -- and monetary policy has responded to that."

Related: Fed finally tapers its stimulus

Why did the Fed do this? After slashing its key interest rate to near zero in 2008, the Fed needed to find another way to stimulate the economy. It decided to buy massive amounts of bonds in the form of U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.

By doing so, the Fed could effectively push down longer-term interest rates, affecting everything from mortgages to business loans. Suddenly, it became cheaper to buy a house, purchase a car or fund a business.

In one regard, the policy worked. Interest rates did fall to record lows. In May 2013, it was possible to get a 30-year mortgage at a 3.4% interest rate -- the lowest in history. Consumers could take out a 48-month loan for a new car, and pay just a 4.1%, also a historic low.

But there was a catch. Only borrowers with pristine credit could qualify for those low rates. Following the financial crisis, credit standards remain tight. Take for example, what it takes to get a mortgage these days: The average application now totals around 500 pages, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

So the Fed is pumping money into the economy, but it's not all being lent out.

Where is it all going? Much of the money still sits on on the sidelines, in bank reserves.

How did the Fed pay for this? That's the unique and mysterious thing about the Fed. It can essentially create money out of thin air.

Does the Fed need to sell all those assets? Not necessarily. When (or if) the economy eventually picks up steam, Federal Reserve officials have indicated they may allow many of the bonds to simply mature.

So how will they eventually rein in all that money so the economy doesn't overheat? The Fed is testing a new tool that would allow it to pay banks and money market funds a higher interest rate to hold their money at the Fed overnight, rather than lending it out.

Through this tool -- called an overnight fixed-rate full allotment reverse repo facility (we know, it's a tongue twister) -- the Fed can prevent excess money from sloshing around in the economy, without actually having to sell its bonds. (Read more about how reverse repos work)