Millennials are starting to get restless for change.

Stuck in low-wage or part-time jobs with mountains of student loans to pay off, the generation that came of age in the new millennium finds itself in a hopeless situation. Despite being better educated than previous generations, many young people are shut out of the middle class with no road map of how to get there.

So many of them are joining protests, showing up at rallies, or forming unions to improve their situation.

In the past year, millennials turned up the heat against low wages at Victoria's Secret, Wal-Mart (WMT), McDonald's (MCD), Wendy's (WEN), KFC (YUM) and others like Kaplan (GHC), which runs tutoring centers.

Some achieved a measure of success. Debbra Alexis, a 27-year-old Victoria's Secret employee with a bachelor's degree in health sciences, gathered more than 800 signatures in support of her campaign for higher pay at her New York City store. The store, part of L Brands (LB), ended up giving across-the-board raises of about $1 to $2 per hour to all workers in the Herald Square store.

A group of Kaplan tutors in New York City also formed a union to bargain for higher pay.

Some fast food workers wrangled wage increases or better hours. But union-organized rallies are calling for broad-based change and minimum wages of $15. Wal-Mart workers nationwide have also protested, calling for higher pay and more hours.

Related: The real budget of McDonald's workers

Janah Bailey has participated in several strikes in Chicago, where union-backed groups Fast Food Forward and Fight for 15 have been calling for $15 an hour pay.

Bailey, 21, is studying to be a cosmetologist and works two jobs -- 40 hours at Wendy's (WEN) and 12 to 16 hours a week at McDonald's (MCD). Her weekly paycheck is usually about $400, or about $20,000 a year.

Bailey is the primary caregiver of her family of two younger siblings and mom. She pays $750 a month for rent, $50 for heat and $300 for groceries. Her checking account has $5 and her savings account is empty.

Related: Worker wages: Wendy's vs. Wal-Mart vs. Costco

Bailey worries about her future and whether her education will land her a better job.

"We see a lot of people who get degrees and they're still struggling to find better paying jobs," she said. "I'm speaking out because my plan may not land me where I want to go."

Bailey's concerns are not unfounded. The number of minimum wage workers with associates degrees, or in occupational programs like she is, more than doubled to 223,000 from 2007, according to the U.S. Labor Department.

The number of college graduates in minimum wage jobs also doubled during the recession to 284,000 in 2012 from 2007.

"They're coming out of college with huge debts and having to take low-wage jobs. [So they're] trying to fight back," said Bill O'Meara, president of the Newspaper Guild of New York, which represents a group of Kaplan tutors in New York City who unionized hoping to bargain higher pay.

Middle class jobs have lost ground just as millennials have entered the workforce. Some 58% of the jobs created during the recent economic recovery have been low-wage positions like retail and food prep workers, according to a 2012 report by the National Employment Law Project. These low-wage jobs had a median hourly wage of $13.83 or less.

Median household income has also dropped by more than $4,000 since 2000, according to the Census Bureau.

Heidi Shierholz, an economist at the Economic Policy Institute, said more young people are joining protests now because the unions' demands resonate with them. Raising the minimum wage and securing better hours, or speaking up for better working conditions, are a big part of the public discourse of the times.

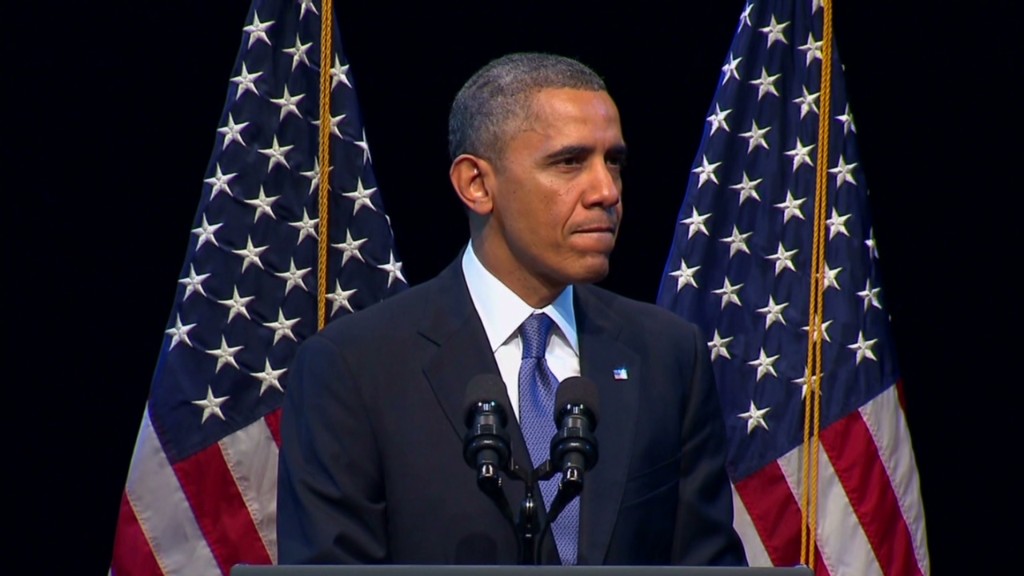

President Obama has lately talked about rising inequality and called for a higher minimum wage.

In a speech earlier this month, Obama said, "We know that there are airport workers and fast food workers and and nurse assistants and retail sales workers who work their tails off and are still living at or barely above poverty. And that's why it's well past the time to raise a minimum wage."

Bailey, the Chicago fast food worker, said such political backing gives her hope that things can change.

"Every time I think of the campaign, I think ... it would be a victory," she said. "It would mean financial freedom."