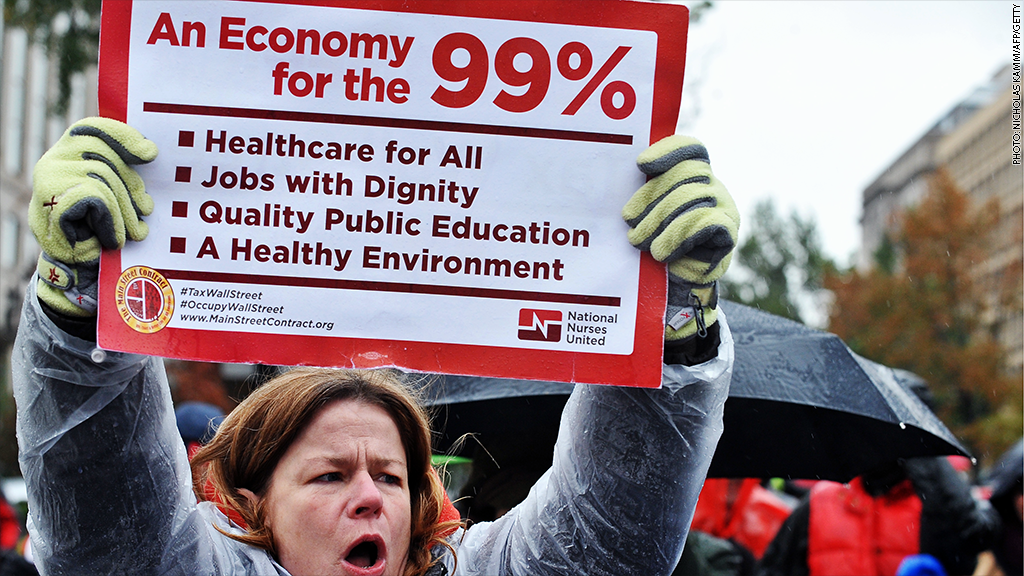

With long-term unemployment historically high and economic insecurity still pervasive in the wake of the Great Recession, it's understandable that many Americans have grown more concerned about the nation's levels of inequality.

Too many families struggle in poverty, too many workers have given up looking for work, and too many young adults have graduated into a weak economy that will lower their lifetime earnings.

|

| Scott Winship is the Walter B. Wriston Fellow at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. |

If the economy were stronger, there is reason to believe inequality would not be such a concern. For instance, inequality was high and rising during the late 1990s, but because the growing economy was largely benefiting everyone, few people were worried about income concentration at the top.

What's more, living standards have improved over time for the poor and middle class even as income inequality has grown. For that matter, the growth in inequality has been exaggerated. And contrary to claims that rising income inequality has hurt their economic opportunity, evidence of a link between the two is weak.

Average income in the middle fifth of households rose 66% between 1969 and 2007 and it grew 55% in the bottom fifth. This growth was much slower than it was in the 1950s and '60s. But the slowdown actually began in the 1970s, before income concentration at the top started to take off.

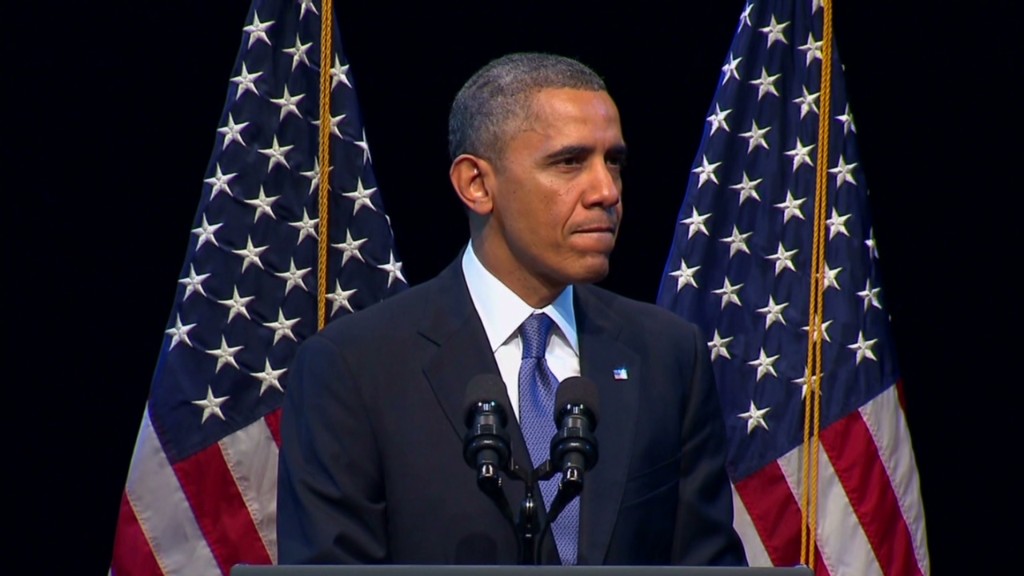

Opposing view: Why growth in income inequality does matter

Economic mobility hasn't changed much either. No research shows a sizable increase in mobility since the mid-20th century. And the most common change found in many studies is so modest (up or down) as to be statistically insignificant.

In the face of this unsupportive research, proponents of the view that inequality has hurt mobility have turned to cross-national research, notably the "Great Gatsby Curve." This chart shows a strong statistical relationship between countries' inequality levels and the mobility their citizens enjoy.

But it's problematic as evidence for several reasons. The most damning: it uses a measure that automatically assigns a country a lower mobility value when its growth in inequality is greater than in other countries.

New research by the creator of the Great Gatsby Curve, which does not automatically adjust mobility downward when there are differences in inequality between nations, suggests that there may be no cross-national relationship between high inequality and low mobility.

While there's reason to believe mobility has not diminished much if at all over time, it has been stuck at unacceptably low levels for decades.

If past patterns hold, 70% of poor children today will fail to make it to the middle class as adults. Four in 10 will be mired in poverty themselves in midlife.

Related: How to be rich and believe in equality

These are not the kind of odds those of us solidly in the middle class would accept for our children. The American Dream is in poor health if children who grow up in the bottom can aspire only to fill the same sorts of jobs as their parents hold.

The challenge is to identify real solutions to the problem of limited mobility. Fifty years after Lyndon Johnson's declaration of war on poverty, we should establish a second front against immobility.

Attacking inequality, however, is unlikely to mitigate either problem.