Wozniak and Jobs. Gates and Allen. Page and Brin.

Many of today's iconic companies were founded by pairs, but cofounders' relationships are seldom so harmonious.

In fact, 65% of high-potential startups fail as a result of conflict among co-founders, according to Noam Wasserman, a professor at Harvard Business School who studied 10,000 founders for his book "The Founder's Dilemma." Pairs and groups bring a variety of skills, but there is also more potential for conflict -- over leadership, money, strategy, credit and blame.

"The fact of the matter is that co-founders spend most of their time fighting," says Los Angeles venture capitalist Mark Suster. "But no one talks about it."

Still, investors increasingly prefer to invest in teams. To hedge their bets against relationships going bad, investors scrutinize the dynamic between co-founders just as much as a startup's idea. A business plan and customer base can change, but a founding team doesn't.

Related: 9 hot startup accelerators

Investors look for clues in body language, eye contact, tone and whether the team genuinely enjoys each other.

Any hint of discord can kill a deal. Seattle angel investor Jon Sposato walked away from one startup after a co-founder shifted uncomfortably the entire time his partner presented and then jumped in to correct every mistake he'd perceived.

David Kidder, founder of a New York City early-stage investment fund, cut a breakfast meeting short after seeing two co-founders continually interrupt each another. Six months later, the relationship fell apart. "I would have been investing in a broken relationship right out of the gate," says Kidder.

Not surprisingly, the most successful teams tend to be people who worked together in the past, according to Wasserman's research. More surprising, businesses with married couples, family members and friends failed most often because they avoided tough conversations to save hurt feelings, he says.

Suster says entrepreneurs should start companies alone, and then hire top executives with generous equity stakes.

But he's in the minority, especially in the nation's tech hotbeds, where investors tend to look askance at entrepreneurs who make their pitches alone. In fact, only 16% of the 10,000 companies Wasserman surveyed had single founders. The demand for co-founders has even given rise to online "matchmaking" services that pair co-founders by skill, personality and entrepreneurial pursuits.

Related: Get $100,000, give up 6% of your pay

Starting a company can just be too much for one person -- between writing code, crafting strategy, chasing leads and pitching investors, says David Cohen, founder and CEO of TechStars. The Boulder-based accelerator rarely invites individual entrepreneurs to join its program.

Paul English, an angel investor who co-founded Kayak.com, said he made 12 investments in the past two years -- none of them with a solo entrepreneur. English likes the diversity of skills that a team provides and having more than one founder acts as a kind of insurance policy. "Plus," English says, "if one gets hit by a bus, someone else can run the company."

But he won't invest in just any team. English has nixed investments after perceiving shaky relationships between partners, and says a positive dynamic is just as important.

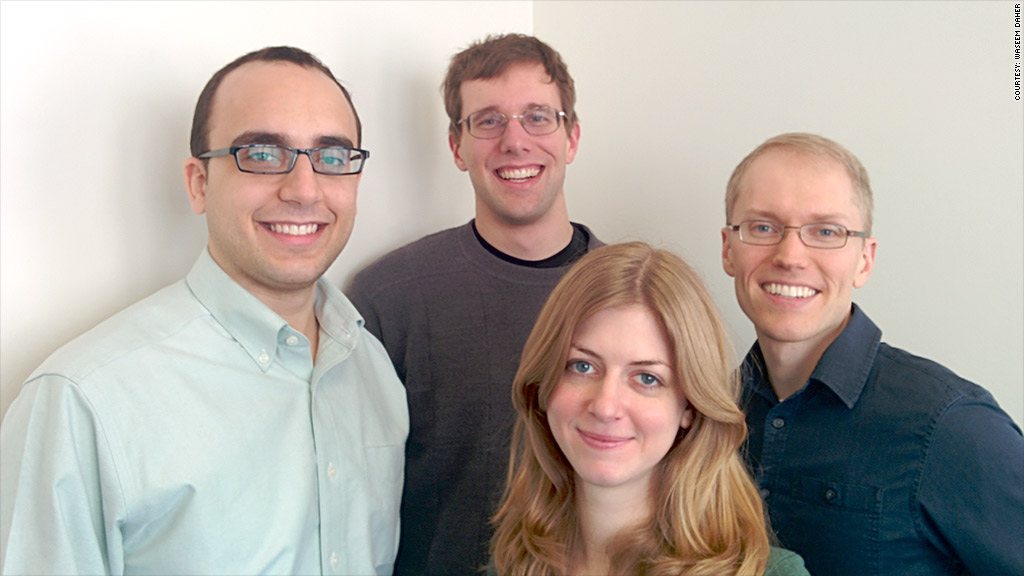

He funded a foursome from MIT even though he didn't like their idea at all. During the presentation, they encouraged their team members to share stories and laughed with one another.

"Their dynamic was so powerful that I would almost invest in whatever they do," English says. He's now working with them on a new project.