What we commonly call the Web is really just the surface. Beneath that is a vast, mostly uncharted ocean called the Deep Web.

By its very nature, the size of the Deep Web is difficult to calculate. But top university researchers say the Web you know -- Facebook (FB), Wikipedia, news -- makes up less than 1% of the entire World Wide Web.

When you surf the Web, you really are just floating at the surface. Dive below and there are tens of trillions of pages -- an unfathomable number -- that most people have never seen. They include everything from boring statistics to human body parts for sale (illegally).

Related story: Shodan, the scariest search engine on the Internet

Though the Deep Web is little understood, the concept is quite simple. Think about it in terms of search engines. To give you results, Google (GOOG), Yahoo (YHOO) and Microsoft's (MSFT) Bing constantly index pages. They do that by following the links between sites, crawling the Web's threads like a spider. But that only lets them gather static pages, like the one you're on right now.

What they don't capture are dynamic pages, like the ones that get generated when you ask an online database a question. Consider the results from a query on the Census Bureau site.

"When the web crawler arrives at a [database], it typically cannot follow links into the deeper content behind the search box," said Nigel Hamilton, who ran Turbo10, a now-defunct search engine that explored the Deep Web.

Google and others also don't capture pages behind private networks or standalone pages that connect to nothing at all. These are all part of the Deep Web.

So, what's down there? It depends on where you look.

Infographic: What is the Deep Web

The vast majority of the Deep Web holds pages with valuable information. A report in 2001 -- the best to date -- estimates 54% of websites are databases. Among the world's largest are the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NASA, the Patent and Trademark Office and the Securities and Exchange Commission's EDGAR search system -- all of which are public. The next batch has pages kept private by companies that charge a fee to see them, like the government documents on LexisNexis and Westlaw or the academic journals on Elsevier.

Another 13% of pages lie hidden because they're only found on an Intranet. These internal networks -- say, at corporations or universities -- have access to message boards, personnel files or industrial control panels that can flip a light switch or shut down a power plant.

Then there's Tor, the darkest corner of the Internet. It's a collection of secret websites (ending in .onion) that require special software to access them. People use Tor so that their Web activity can't be traced -- it runs on a relay system that bounces signals among different Tor-enabled computers around the world.

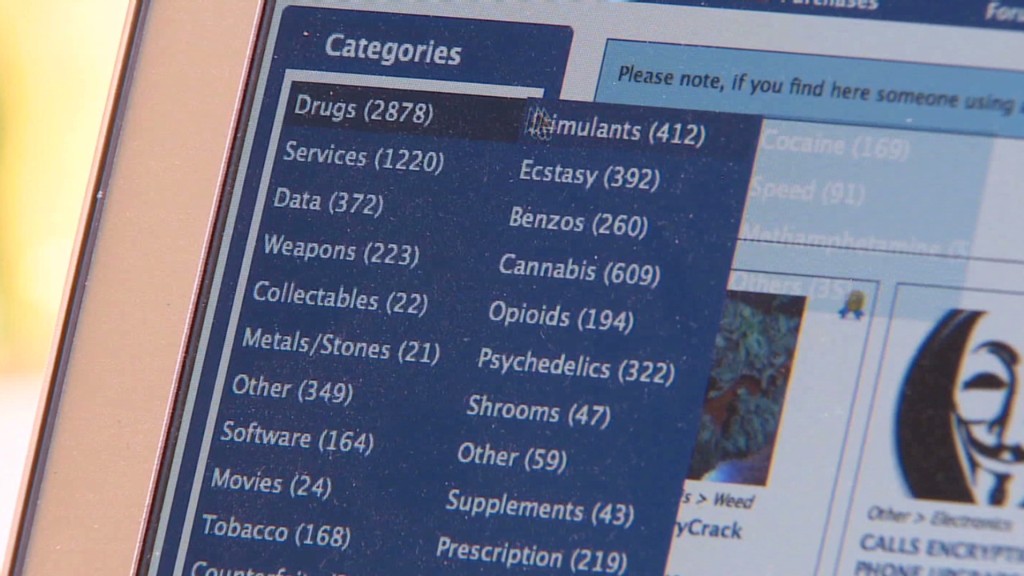

It first debuted as The Onion Routing project in 2002, made by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory as a method for communicating online anonymously. Some use it for sensitive communications, including political dissent. But in the last decade, it's also become a hub for black markets that sell or distribute drugs (think Silk Road), stolen credit cards, illegal pornography, pirated media and more. You can even hire assassins.

Related story: NSA has its eye on Tor

While the Deep Web stays mostly hidden from public view, it is growing in economic importance. Whatever search engine can accurately and quickly comb the full Web could be useful for Big Data collection -- particularly for researchers of climate, finance or government records.

Stanford, for example, has built a prototype engine called the Hidden Web Exposer, HiWE. Others that are publicly accessible are Infoplease, PubMed and the University of California's Infomine.

And if you're really brave, download the Tor browser bundle. But surf responsibly.