The rich are on the hunt for secure, tax-free places to stash their fine art and luxury items, fueling a surge in demand for top-end warehouses known as freeports.

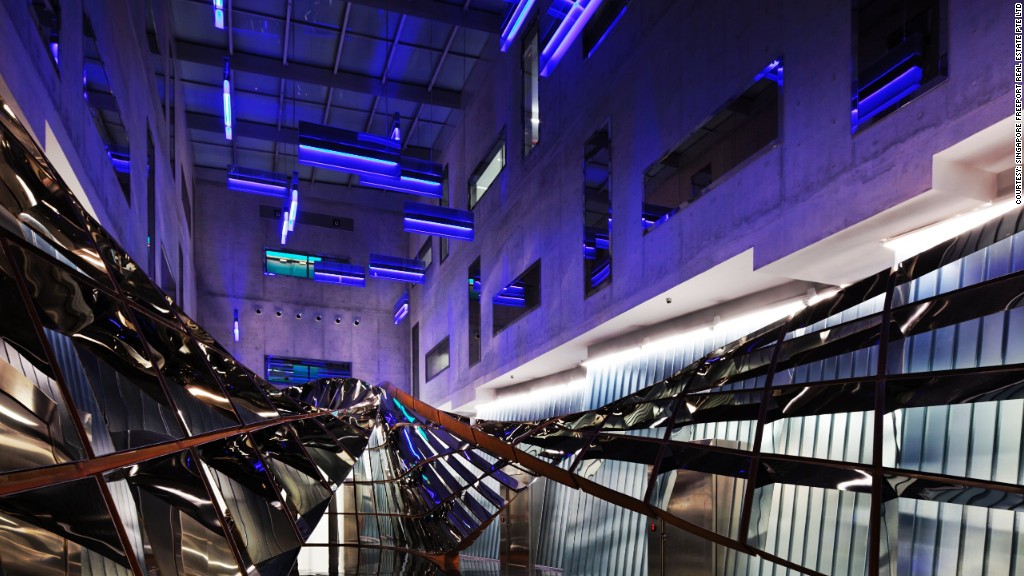

These gigantic storehouses are a far cry from roadside self-service lock ups. The sleek buildings look like Fort Knox from the outside, with security features worthy of a James Bond movie -- invisible laser sensors, body scanners, digital locks, motion detectors, secret door codes, biometric identification, and armed guards.

They scream high-end on the inside too, holding piles of treasure worth billions -- from Picasso paintings to diamonds, gold, fine wines, vintage cars, and more.

Fancy freeports are well established in places such as Switzerland, Singapore and Monaco, with many more opening for business in Luxembourg and China.

The boom in freeport construction has followed an explosion in the global art market. International art sales tripled to more than $66 billion over the past dozen years or so, as the global elite lost confidence in traditional assets and looked for alternative investments.

"As the value of these assets grow, the services of freeports are needed to protect these assets," said Anders Petterson, managing director of art market analysis firm ArtTactic.

Related story: Chinese snap up fine art for use in laundering schemes

The first freeports opened in Switzerland in the late 1880s. They were built to hold bulk commodities in transit, allowing sellers to line up buyers before having to shell out for taxes, such as import duties.

They've undergone a makeover in recent years to cater to the very rich. But the tax-free perk remains, along with a guarantee of privacy -- much like offshore tax havens -- which is luring wealthy art collectors, dealers, corporations, and banks. Demand is so strong that many freeports are full, and those yet to open have already pre-sold much of their space.

Storage costs a few thousand dollars a month, with additional fees depending on the value of the goods. Some freeports also offer related services such as art restoration and framing. And they're often located next to airports, making it easy to ship items.

Freeports are so highly frequented by the wealthy that major auction houses such as Christie's have even set up inside to facilitate direct sales. And the icing on the cake? Transactions within the freeports typically don't incur taxes.

Related story: Sold! An American revamps Christie's

While taxes are due once the item exits the freeport -- for example, import taxes at the final destination -- pieces can change hands countless times without ever leaving the tax-free zones.

Many goods never see the light of day. Some freeport users are more interested in parking their wealth tax-free, or in turning a profit, than in having something nice to decorate their homes.

For the art investor who does resell at a profit inside the freeport, it's even possible to defer U.S. capital gains tax by buying a second item within a certain timeframe, said Diana Wierbicki, who specializes in art law at Withers. The tax liability is then shifted to the newly purchased artwork, she said.

Sparse records exist, as confidentiality is considered an extra layer of security. "While the painting is stored at the freeport, it has no value, no ownership, no inventory list -- everything is confidential," said Lynda Albertson, CEO of the Association for Research into Crimes against Art.

Freeport operators such as private Swiss firm Euroasia say their role is to manage the buildings and provide security, not to keep records.

"That's not our job; our job is to offer the space," said Tony Reynard, chairman of Singapore Freeport, owned by Euroasia.

Related story: The world's most expensive whisky

While customs registration is required at least in Singapore, tenants only "have to list 'one painting,' not 'one painting by Van Gogh,'" Albertson said.

And forget about getting inside one of these for a peek -- the Geneva Freeport said access is strictly limited to its users and declined to comment. Christie's also declined to comment.

Some experts say freeports are fast-becoming a one-stop shop for the art world, and provide a crucial service for a growing market. Others argue that freeports only make the secretive art trade more opaque, attracting criminals and providing cover for corrupt activity -- counterfeiting, tax evasion, money laundering and terrorist financing.

Yet the prospect of creating jobs and attracting big spenders seems to outweigh those concerns for many governments. The planned Beijing freeport is a joint venture between a Chinese state-owned company and Euroasia, and the government owns roughly 80% of the Geneva freeport.