Indian markets are riding high as investors bet that an election and new administration will cure some of the country's economic ills.

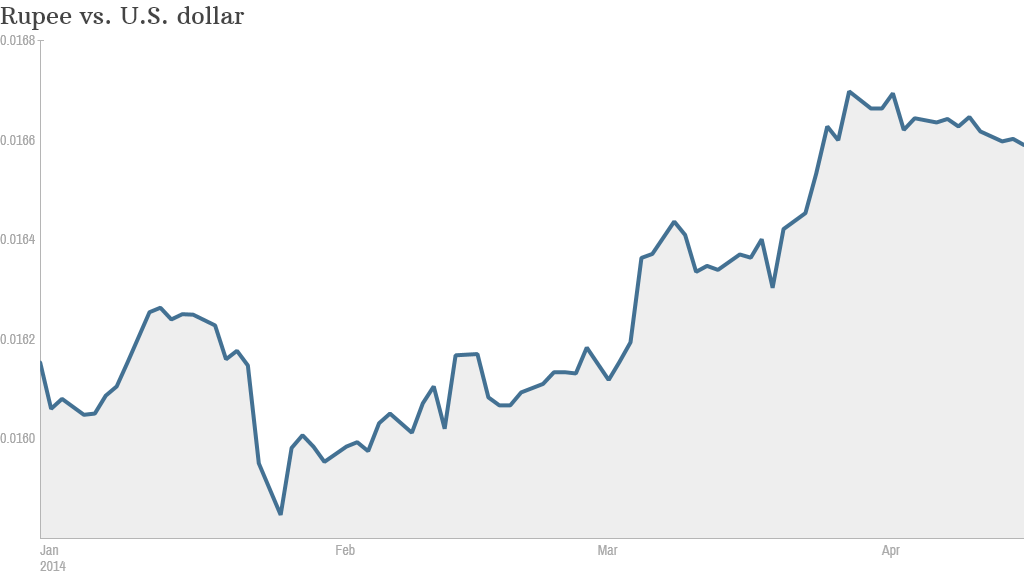

Mumbai's benchmark Sensex index has trounced its Asian peers in recent months, hitting a record high last week and gaining 7% since the start of the year. The rupee has strengthened too, clawing its way back from a dismal performance in 2013.

Much of the optimism hinges on forecasts that India's 815 million voters will make Bharatiya Janata Party candidate Narendra Modi the next prime minister.

Victory for a Modi-led coalition would end the Congress Party's dominance, and create an opening for a new government to implement economic reforms.

Analysts say India would benefit greatly from changes to its tax code, a reduction in excessive bureaucracy and more efficient agricultural policies. Momentum on these long-promised reforms stalled under the leadership of the Congress Party.

India's potential for growth was once mentioned in the same breath as that of China. But the world's second most populous nation and biggest democracy has failed to deliver and its economy is just a fifth the size of its Asian rival.

Economic growth has fallen below 5% in recent quarters, some of the lowest levels in years. The currency has lost more than a third of its value since 2011.

Observers don't expect much improvement this year, a troubling sign for one of the world's top 10 economies.

Modi has presented himself as a candidate in the mold of a CEO, campaigning on his economic record as head of Gujarat state. Investors are hoping that he will be able to conjure some of the same magic on a bigger stage.

Related story: Trial by fire for India's new central banker

But there are plenty of arguments for taking a more cautious view before the election concludes in the middle of May.

India's mammoth exercise in democracy is notoriously difficult to forecast, and polling data is thin. Even if the BJP does well in the vote tally, the party's ability to govern could be hamstrung by its eventual coalition partners.

In addition, the BJP may prove to be less enthusiastic about economic reforms than some observers imagine.

Eurasia Group analysts wrote recently that they expect only "piecemeal improvements," noting that the BJP is not resolutely free-market oriented. Instead, they said, the BJP should be characterized primarily as a nationalist party.

The election will also do little to change India's fractious legislative process, which can even trip up parties with plenty of political capital to burn.

"We continue to believe that the new government's potential accomplishments will be substantially more modest than current market expectations," the Eurasia Group analysts said.

Related story: Investors dip a toe back in emerging markets

Many observers have also expressed concern over Modi's association with Hindu nationalist causes -- a potentially destabilizing agenda.

Much of the criticism centers on Modi's handling of riots between Muslims and Hindus in 2002 that resulted in the deaths of 2,000 people. Modi was accused of not responding quickly or adequately to the tumult, but he has denied any responsibility.

Some are not convinced. The Economist won't back Modi, saying the candidate has stonewalled and refused to explain his role in the violence.

Should Modi choose to pursue a controversial agenda in office, investor sentiment could sour quickly.