A two-year-long legal battle between the country's biggest broadcasters and a startup called Aereo is about to culminate at the U.S. Supreme Court.

The court's decision, expected sometime this summer, could have far-reaching implications for television and technology companies -- and ultimately on how people watch TV programs.

That's because Aereo brings up crucial questions about copyright law and threatens to disrupt lucrative business models.

The court will hear arguments in the case on Tuesday morning. Legal experts are divided about the most likely outcome. But Aereo is undeniably the underdog, opposed by the owners of virtually all the major media companies in the United States.

"We believe that Aereo's business model, and similar offerings that operate on the same principle, are built on stealing the creative content of others," CBS (CBS) said in a statement, echoing the views of others challenging Aereo.

Related: What the heck is Aereo, anyway?

What Aereo says: The startup argues that its service is legal: It simply mimics what millions of Americans already do at home -- hook their television sets up to antennas and watch free TV.

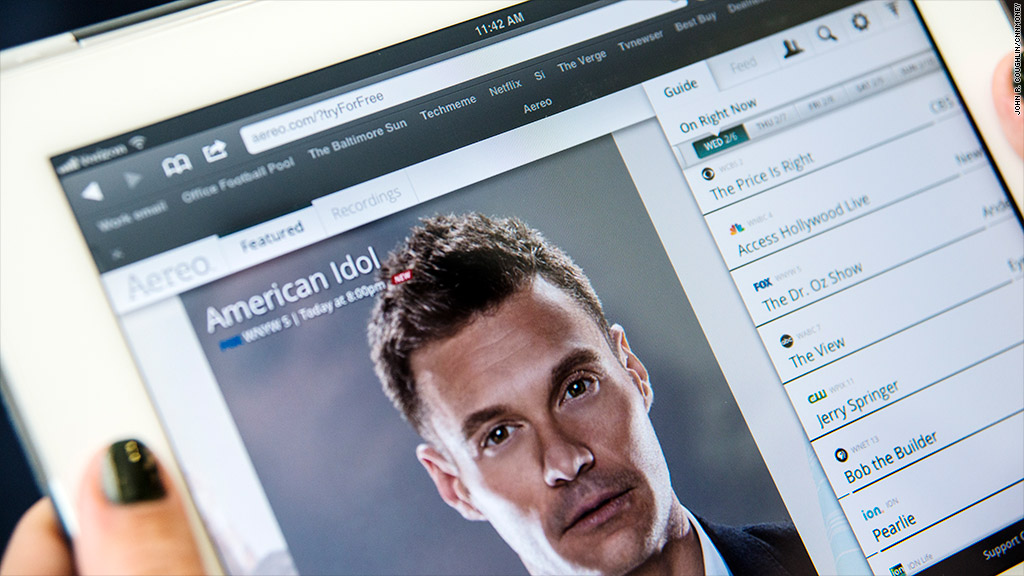

The service scoops up the freely available signals of TV stations using arrays of tiny antennas -- thousands of them, in fact, so that every viewer gets an individual antenna. Then it streams the signals to the phones and tablets of paying subscribers, turning those devices into TV sets without the need for a physical antenna.

"What we're providing is exactly what you can get with an antenna, just done in a way that's modernized, so you're not sitting there tuning your rabbit ears," Chet Kanojia, the founder of Aereo, said in an interview broadcast on CNN's "Reliable Sources" on Sunday.

Aereo also includes a digital video recorder feature that functions via the Internet, or "in the cloud," so subscribers can save shows and watch them later. The service doesn't recreate cable, because it only carries what's available through an antenna. But for a Web-savvy individual who just wants access to a smattering of TV channels, it serves as an alternative to cable.

Some big-name investors, including Barry Diller's IAC (IACI), are backing the venture.

What the broadcasters say: The owners of ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC, Univision and other broadcasters argue that Aereo qualifies as a "public performance" of the TV shows they distribute, something that is prohibited under the Copyright Act.

(Time Warner (TWX), the parent company of CNN and this Web site, is not a plaintiff in the case because it does not own local TV stations. But in a court filing, it sided with the broadcasters and said "the court's intervention is urgently needed now to set this vital area of copyright law back on course.")

The broadcasters first filed suit a few weeks after Aereo was introduced in New York City on Valentine's Day 2012.

The lawsuits were hardly surprising, since local broadcasters say that an Aereo-like arrangement -- antenna arrays and streams to subscribers -- undermines their business.

Stations' signals are given away free over the public airwaves. But most Americans receive them another way, through a pricey cable or satellite company. And those companies, in turn, pay the stations for the right to retransmit them.

Such "retransmission fees" have become a critical revenue stream for broadcasters, offsetting declines in advertising revenue. The broadcasters argue that if Aereo is found to have solid legal standing, then the cable companies might stop paying those fees.

Kanojia disputes that idea. He notes the cable companies are "constrained by what's called retransmission consent," a law that isn't at the crux of the copyright infringement case now before the Supreme Court. He says the broadcasters have tried to "strangle us with lawsuits."

What's at stake: There is also disagreement about whether the Aereo case could effect the emerging industry of cloud-based media storage.

Kanojia and his company's allies have warned that a Supreme Court finding that Aereo is illegal could imperil a vast number of other companies that store songs, videos and other files via the Internet.

The Obama administration, which has sided with the broadcasters at the Supreme Court, says the court should rule more narrowly. It said a ruling against Aereo doesn't have to undermine startups that give consumers "new ways ... to store, hear, and view their own lawfully acquired copies of copyrighted works."

Ultimately, a ruling in Aereo's favor may encourage more alternatives to the traditional cable TV bundle that most Americans currently have. Conversely, a ruling against Aereo may give major media companies a stronger hand.

At the moment, Aereo is more a symbol of disruption than a sturdy business. The company won't say how many subscribers it has, but it is only available in a dozen markets.

If Aereo wins in court, it will try to expand into more local markets right away. And if it loses, the service will most likely go extinct. As Diller has repeatedly said: "There's no plan B."