In high-stakes arguments on Tuesday, the Supreme Court's justices challenged an attorney for Aereo to defend the legality of the television streaming service and explain the logic underpinning it.

The arguments summarized two years of legal tussling between Aereo, which provides streams of local television stations to paying subscribers, and the owners of those stations.

The TV station owners, major media companies like Disney and CBS, say that Aereo is violating copyright by allowing "public performances" of shows. Aereo says it is only enabling private screenings, just like off-the-shelf TV antennas do.

Several of the justices, in their questioning, repeatedly expressed concerns that a broad ruling against Aereo would imperil the nascent cloud computing industry because of how Aereo works. They seemed to search for a way to avoid that outcome.

"This is really hard for me," Justice Sonia Sotomayor remarked early on in the hour-long hearing.

"I'm hearing everybody having the same problem," Justice Stephen Breyer said, as he evoked concern about "somehow catching other things" such as cloud computing in a ruling intended to address only Aereo.

Afterward, representatives of the broadcasters cited the questioning as evidence that they'd come out ahead.

"The justices understood the technology. They understood the stakes in the case," the attorney for the plaintiffs, Paul Clement, said in a statement.

Conversely, the lawyer for Aereo, David Frederick, said the company was "cautiously optimistic" the court would embrace its position.

The justices are expected to issue a ruling by early summer.

Related: What the heck is Aereo, anyway?

The formal issue before the Supreme Court is "whether a company 'publicly performs' a copyrighted television program when it retransmits a broadcast of that program to thousands of paid subscribers over the Internet."

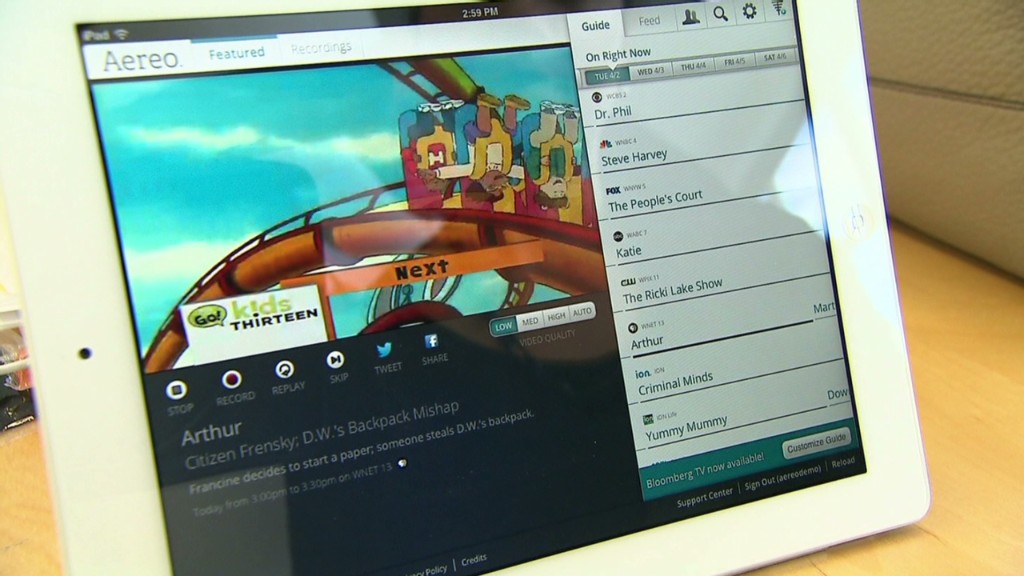

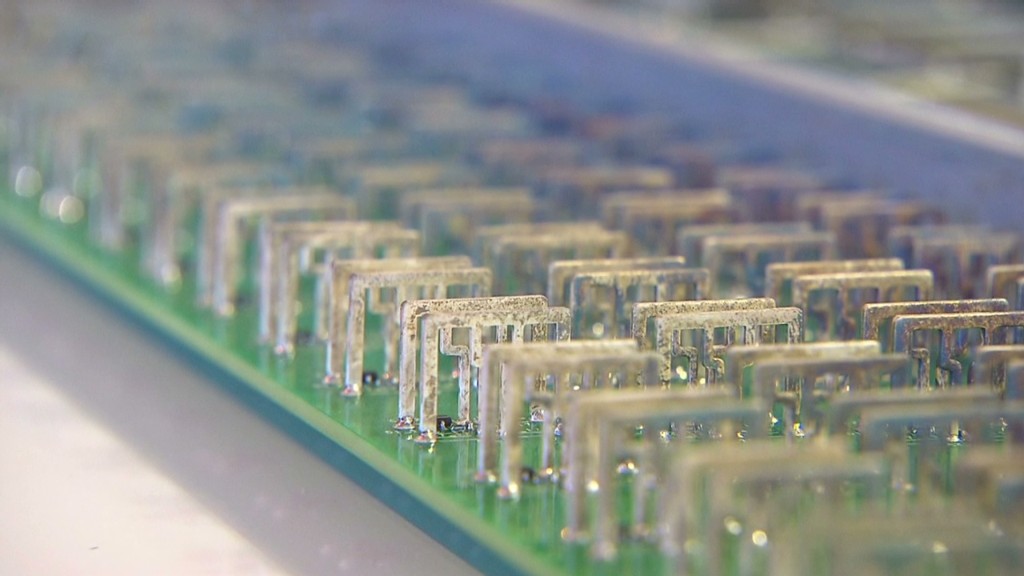

Using thousands of miniature TV antennas, Aereo scoops up the freely available signals of local stations. Then it delivers the signals to smart phones, tablets or computers via the Internet. Subscribers pick what to watch through a traditional on-screen guide. They can also record shows and stream them later.

The owners of ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC, Univision and other broadcasters argue that Aereo qualifies as a "public performance" of the TV shows they distribute. (Time Warner, the parent company of CNN and this Web site, is not a plaintiff in the case, but it is supporting the broadcasters.)

On Tuesday, there was considerable discussion about what constitutes a "public performance" and what does not.

The justices quizzed Frederick, the Aereo attorney, about why the Aereo system is set up the way it is. Some of them implied it was designed to skirt the Copyright Act.

"There's no technological reason for you to have ten thousand dime-sized antennas, other than to get around the copyright law," Chief Justice John Roberts said.

Frederick tried to rebut that by describing the "hassles" of operating one giant antenna: "We wanted to tell consumers, 'You can replicate the experience [of owning a TV antenna] at very small cost.'"

At one point Frederick described Aereo, rather plainly, as an "equipment provider," seeking to analogize it to retailers like Radio Shack that sell antennas.

Clement sought to refute that point, saying Aereo is "not just a passive bystander." He made it sound more like a pirate. In his closing remarks, he called the startup's logic "just crazy."

Watch: Amazon's plan to rule TV

Some of the justices showed proficiency with state-of-the-art technology. Sotomayor mentioned Dropbox and iCloud and said she owned a Roku streaming media box.

Justice Antonin Scalia, on the other hand, seemed not to understand the difference between television networks that are beamed over the public airwaves, like ABC, and those that are only available through cable subscriptions, like HBO.

Scallia's hypothetical question to Frederick -- in the future, "you could take HBO, right?" -- earned him some ribbing on blogs after the court session.

Malcolm Stewart, a deputy solicitor general at the Department of Justice, supported the broadcasters on behalf of the Obama administration. The Justice Department and the United States Copyright Office took a public position against Aereo earlier this year and called it "clearly infringing."

"What Aereo is doing is really the functional equivalent of what Congress in the 1976 [Copyright] Act wanted to define as a public performance," Stewart told the justices on Tuesday.

A number of media heavyweights were in attendance. Among them were Barry Diller, the IAC/InterActiveCorp. (IACI) chairman whose investment helped Aereo launch two years ago, and James Murdoch, the co-chief operating officer of 21st Century Fox, one of the many companies suing Aereo.