The last time the European Central Bank cut interest rates, it took investors by surprise. It will be a shock if the central bank doesn't cut them further Thursday.

Expectations of new action to boost the economy have increased sharply over the past month as evidence mounts that Europe's recovery is stuck in first gear.

Growth this year has been disappointingly weak, and France and Italy in particular are hurting.

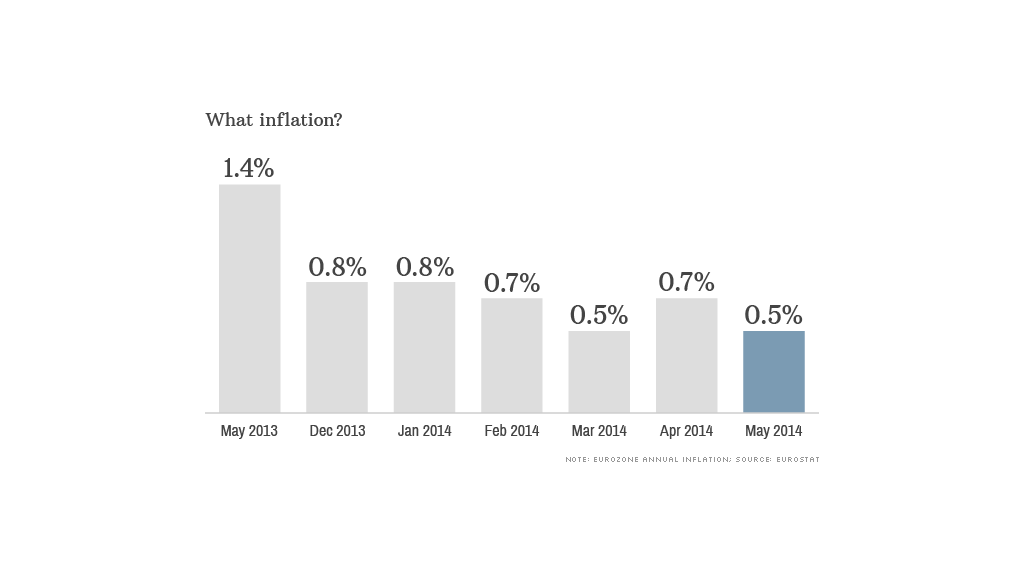

Last month, consumer prices in the eurozone rose just 0.5%, reinforcing fears of stagnation.

Very low inflation can be as damaging to an economy as excessive price increases.

If households and businesses expect inflation to stay depressed for a long period, they may postpone spending and investment, triggering a downward spiral and raising the risk of outright deflation.

It also makes it harder for countries to pay off debts, and forces weak European economies to make real cuts to wages to compete with countries like Germany.

ECB President Mario Draghi dropped the heaviest of hints a month ago that the bank was readying a variety of weapons to counter those risks.

"The governing council is comfortable with acting next time, but before, we want to see the staff projections that come out in early June," he said.

Related: Britain, Italy include drugs and sex in GDP

The ECB will review those updated forecasts for growth and inflation before announcing its policy decisions at 7.45 a.m. ET Thursday.

Draghi said in May the bank stood ready to cut rates or print money through a program of Federal Reserve-style asset purchases if necessary.

The main interest rate has been at a record low of 0.25% since November 2013, the last time rates were cut.

Public remarks by Draghi and other ECB officials since the May meeting have reinforced expectations that action will be forthcoming.

The euro has fallen 2% against the dollar as a result, bringing some relief to exporters and easing the pressure on prices by making imports more expensive.

So what will Draghi do?

Cutting the main interest rate to 0.15% or even 0.10% looks like a done deal. Many economists also expect the central bank to take a step into the unknown by cutting its deposit rate from zero into negative territory.

That would have the effect of charging banks for parking spare cash with the ECB, in theory providing an incentive to lend that money to firms and consumers instead. But there is a risk that the experimental move could backfire.

There's also a good chance the ECB will offer cheap, long term loans to banks, possibly with the explicit aim of boosting lending to the thousands of small businesses that form the backbone of the European economy and lack access to other sources of finance.

Draghi is likely to stop short of launching a full-blown quantitative easing progam, but will keep the option firmly on the table.