The early bird is paying more for his worm these days.

If you're keeping a closer eye on your pocket book, you're feeling a pinch when you go to the grocery store.

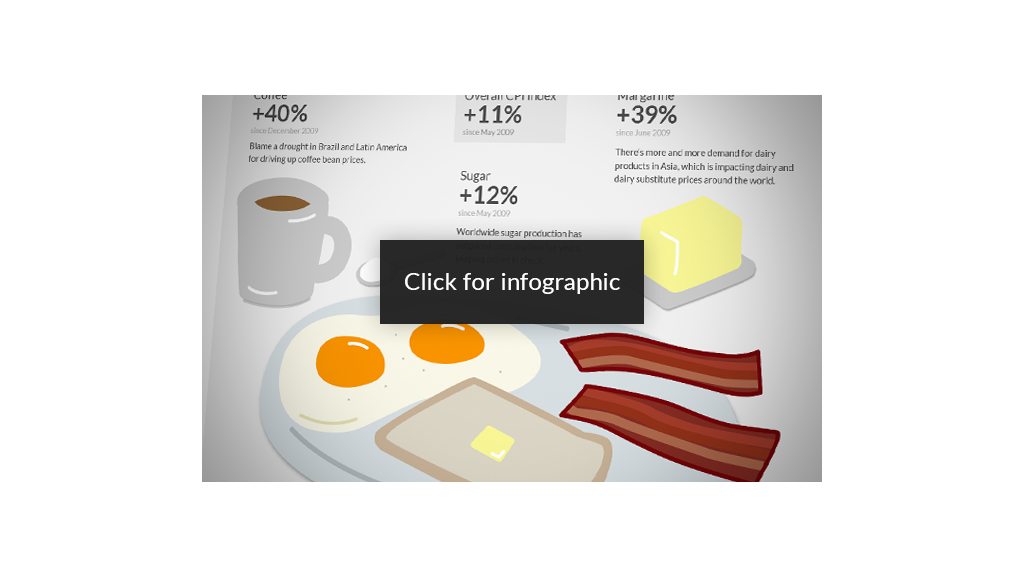

Many popular breakfast items like coffee, bacon and sugar fluctuate in price if something happens to a lot of crops or animals. And lately, there have been a lot of "freak events."

A type of diarrhea killed a lot of pigs, driving up bacon costs, and a drought in Brazil pushed coffee prices higher.

Related: Is Perfect Bacon Bowl the next Snuggie?

How much of a hit these price spikes are causing to your wallet depends on your typical basket of groceries or your favorite breakfast plate.

Luckily, food prices usually don't all go up at the same time. Processed foods, including bread, see less price variation and are easier to store for the long haul.

"The fresh items that [people] would put in their breakfast will be increasing more than box-item cereals," said Annemarie Kuhns, an economist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service.

She said the USDA expects food prices to increase between 2.5% and 3%, in line with the historical averages. Larger increases in fresh items like meat and fruit should be balanced with slower price growth in processed and pre-made goods.

But mother nature acting up isn't the only thing that makes food more expensive.

Macroeconomic shifts, like the growing middle classes of emerging markets in China, impact prices as more people eat more meat and processed foods. There's more demand for these goods, and the supply hasn't entirely caught up with that yet. This year's booming milk market is a prime example.

Related: Growing demand in China has been a boon for milk producers this year

Often, businesses from groceries to restaurants try to hedge against food price increases by paying months in advance to lock in a good price or buying forms of insurance to protect against fluctuations. But that doesn't always pan out.

"Restaurants can generally make internal adjustments to deal with temporary spikes of individual commodities, but it could pose significant challenges if overall wholesale food prices remain elevated for a longer period of time," wrote Annika Stensson, a research spokeswoman for the National Restaurant Association, in an email.

That's what happened with companies like Starbucks (SBUX) and J.M. Smucker (SJM), which have both recently raised consumer prices when coffee beans didn't come down in cost for several months. At some point, companies have to pass those higher prices on to consumers.

Related: Starbucks can't outlast coffee spike, raises prices

Food prices tend to be more volatile than most goods. That's why official inflation data typically excludes food and energy in the calculation. Thus, many investors and Federal Reserve watchers place less weight on food costs as an economic measure. But that doesn't mean they're meaningless.

"Having to spend more on food raises the cost of living as much as having to spend more on anything else," said Larry Ball, a professor a Johns Hopkins University who studies macroeconomics.

People feel it every time they go to the grocery store, especially if they buy a lot of the items that are going up in price.

Still, Ball says we're nowhere near what happened in the 1970s when prices of many items -- even beyond food -- were rising rapidly.