Saket Soni doesn't usually count meetings, but the other day he couldn't help it: 17. "It's not that healthy to have 17 meetings per day," he concedes; 10 to 12 is the limit.

Some begin with a dial-in, some with the tchwap of butcher paper tearing — a fresh sheet for a group strategy session. Others are free-form, like when Soni counseled a woman struggling to organize construction workers. They walked together, did breathing exercises. The ocean sounds in Soni's iTunes library provided backdrop for guided meditation.

"When you're an organizer, nothing is too small," he says.

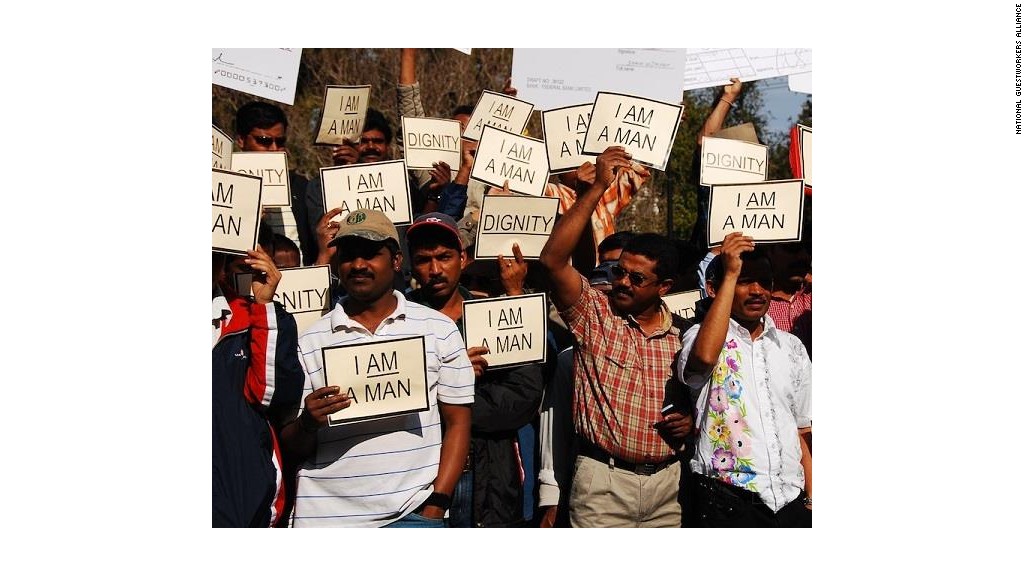

Conference calls can be memorable, too. The labor organizer has conducted them in church stairwells, outside labor camps, inside ICE detention centers. On Easter weekend six years back, Soni joined a conference call while marching with dozens of Indian welders from Montgomery, Alabama, to Atlanta, Georgia. Like many of the people who find their way to Soni, the welders had been screwed. Recruiters had convinced them to pay $20,000 for a green card and the chance to help rebuild post-Katrina New Orleans. Forced labor and squalid trailers awaited them.

More from Ozy: A Surprising Dream Job: Being "Zach Galafinakis"

The organization Soni directs, the National Guestworker Alliance, focuses on immigrants with temporary work visas. Hundreds of thousands come to the United States each year. Despite their numbers, they're difficult to organize: transient, for starters; vulnerable and risk averse, besides. Guest workers don't come here to make trouble. Because their visas bind them to one employer, quitting means deportation, or worse.

Soni has led guest workers to some of the ballsiest collective actions in recent history — the welders, for instance, ended up marching all the way to Washington, D.C., going on a hunger strike and catalyzing an uproar in India and the White House. A strike by Mexican crawfish-peelers — who'd been forced to work 16- to 24-hour shifts and threatened with bodily harm — changed corporate policy at Wal-Mart. Striking student guest workers at a Hershey packing plant led the State Department to rewrite certain visa policies.

More from Ozy: From a Six-Week Course to Six-Figure Salary

More remarkable than all this, maybe, is what Soni thinks the guest workers represent: you.

"The guest workers and low-wage workers that I organize hold a crystal ball into the changing nature of work," he argues. It's part of a theory about the future of work that he's elucidated in lectures at Harvard Law School, Soros-funded forums, on television and, soon probably, in a book. "What's happening to low-wage workers is not just happening to low-wage workers," he says .

What's happening is the rise of contingent labor — temporary, part-time, gig-to-gig — and the lengthening of labor supply chains, like independent contractors and sub-subcontractors. In their wake, even American-born professionals have lost leverage. At universities, adjunct professors are paid per class, hired per semester. Lawyers who used to work at firms now contract for them. Sixty-four thousand Silicon Valley engineers just won a settlement against four tech giants who'd agreed not to solicit one another's employees. To Soni, their plights all resemble guest workers'.

Stories about abused guest workers once elicited sympathy, Soni says. Now they elicit recognition. "There's a real national panic about work that has not been named in our society," he says. "It's a United States of Anxiety."

Of course, it's in Soni's strategic interest to describe a common plight. Many Americans would resist the notion that they share a boat with guest workers; they're more likely to think about guest workers as threats to their own jobs. That's if they think about guest workers at all. Guest workers are just slightly less invisible and marginalized than when Soni started his work.

But within the labor movement, the idea that we are all guest workers now has force.

More from Ozy: What a College Degree is Really Worth

"Saket could well be one of the architects of the next labor movement in the United States," says George Goehl, no organizing slouch himself. Soni's "future of work" analysis packs as much disruptive punch as Al Gore's An Inconvenient Truth, Goehl says, though for years the packaging wasn't fancy. ("There was something charming about seeing him show up at meetings and take that butcher paper out of his backpack," says Goehl.) It's fancier now, enough to sway hundreds of skeptical organizers around the country, including those who work with Goehl.

Despite the seriousness of his work and his immersion in it — even his partner, Marielena Hincapié, is a prominent immigrant advocate — Soni seems boyish: baby face, sweep of dark hair, open demeanor, short stature. Without his goatee and glasses, he'd look younger than his 36 years.

He spent his childhood in Delhi, and his parents, though not particularly political, sent him to a school where Soni felt he was "in a swirl of social forces: You were writing a school play and it was about Nelson Mandela; then you were going out to protest [against] the Indian cricket team going to South Africa; and then you were meeting with Nelson Mandela because he was free.

"And we were told it happened only because of us — and because we were kids, we believed it."

With a sense of protagonism and possibility, Soni went to the University of Chicago on a full scholarship. He studied theater and, after college, worked at a theater company whose scripts were based on the immigrant experience. Rent came from sweeping floors and washing dishes and cars. He overstayed his student visa just in time for the post-9/11 crackdown on foreigners.

That period was a crucible, he says, "being undocumented and entering into a period of low-wage work, and in the meantime trying to continue to work in the arts, and eventually defending more and more people from deportation."

On the other end of it, Soni emerged an organizer. "Just because the political climate was really bad, I would not give in and self-deport," Soni says he told himself. "I would stay and be part of a rebuilding of democracy in this country." That immigrant idealism about America stayed with Soni through the horrors he said he saw in the years after Hurricane Katrina and during his work at the National Guestworkers Alliance.

He retains a sense of the dramatic, too. For Soni, strikes, demonstrations and marches are all forms of public theater — except the stakes are real and high. On the eve of a Mexican strawberry picker walkout in Louisiana, Soni met with the workers and a few others in their trailers, rehearsing and gathering courage. The boss had abused them and confiscated their passports. Everyone was frightened. The workers wrote one word, "Dignidad," on placards.

The next day, at the appointed hour, the workers rose from the strawberry fields, pulled the placards from under their shirts, and began to march toward the boss. They'd eventually get their passports back, but what stays with Soni is the beauty of it: "To see these workers walking toward us, holding these signs — what a gorgeous image," he says.