Low-income consumers struggling to pay their Obamacare premiums may soon be able to get help from their local hospital or United Way.

Some hospitals in New York, Florida and Wisconsin are exploring ways to provide such aid, which would at least partly guarantee the hospitals get paid when the consumers seek care.

But the hospitals' efforts have set up a conflict with insurers, which worry such programs will add too many sick people to their rolls. The premium assistance could drive up costs for everyone and discourage healthier people from buying coverage, insurers wrote recently to the Obama administration.

Some hospital groups are already moving to set up programs through foundations or other non-profit groups, based on applicants' income, not health status, which a recent federal advisory said was allowed.

"We saw the need in our community," said Sarah Listug, spokeswoman for United Way of Dane County, a Wisconsin group that has raised $2 million from a local hospital system. The donations will help more than 650 low-income policyholders pay their premiums. "We have had calls from all over the U.S. asking how to set up partnerships like this."

The South Florida Hospital and Healthcare Association is seeking at least $5 million in donations from member hospitals.

And members of the Healthcare Association of New York State, which represents 500 hospitals and nursing homes, are considering expanding consumer assistance programs.

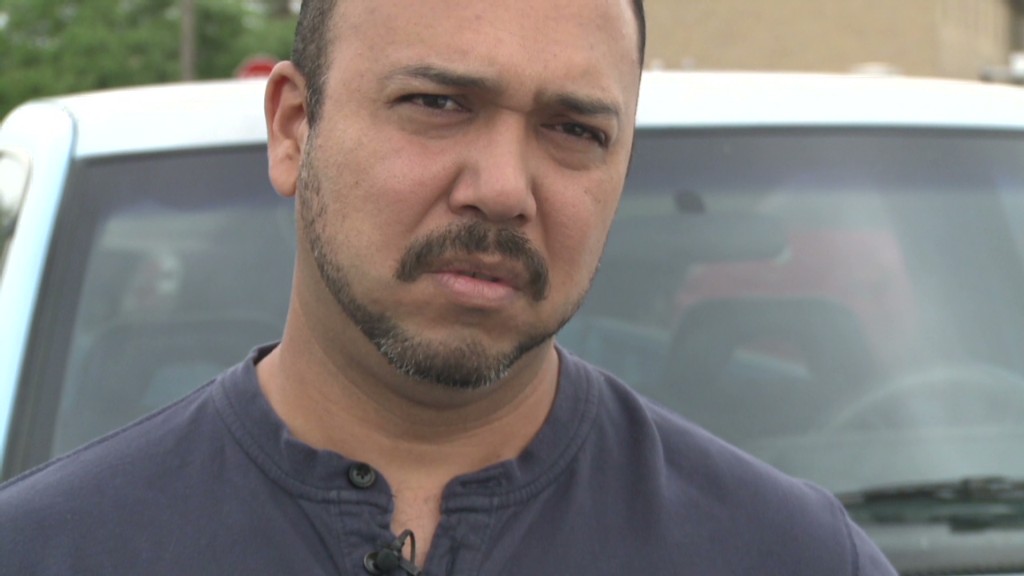

Related: Latinos not signing up for Obamacare

Hospitals or their foundations have long paid premiums for some patients — often those who fell behind after leaving their jobs and footing the entire cost of their coverage under COBRA.

But the issue of these types of payments has taken on new urgency because the federal health law could leave providers on the hook for unpaid bills. The law requires insurers to give subsidy-eligible enrollees who fall behind on premiums a 90-day grace period.

Insurers, in turn, may hold off paying these enrollees' bills for the final 60 days of that grace period -- and ultimately, deny payment if the patient doesn't catch up on premiums. That means doctors and hospitals face the prospect of not getting paid for their services or of having to seek payment from their patients.

That's a big incentive for providers to help pay those premiums.

"It's a situation where patients will be better off and the providers are better off as well if patients are able to maintain coverage," said Mark Rukavina, who consults for the hospital industry on medical debt.

Related: Obamacare help was in high demand

Insurers are urging the federal government to prohibit hospitals from selecting participants based on their health and also from directly paying premiums.

"If third parties provide incentives to gain coverage only once someone is sick, that will -- as the administration has warned -- clearly lead to a less healthy risk pool and put upward pressure on premiums for everyone," said Brendan Buck, a spokesman for the trade group, America's Health Insurance Plans.

But Jeffrey Gold, senior vice president and special counsel at the New York hospital group, says insurers' rates already assume a certain percentage of policyholders will be sicker than average.

"If a couple of people who show up at hospitals or other providers have a premium lapse, I don't understand why someone making them whole [by paying their premiums] would skew the risk pool," he said.

To avoid problems, hospitals are drafting selection criteria tied to income level -- and are paying consumers' premiums for an entire year, rather than simply when they lapse.

In the Wisconsin program, for example, eligible residents must live in Dane County, earn between 100% and 150% of the federal poverty level -- about $11,490 to $17,235 for an individual— and enroll in a subsidized silver plan.

In South Florida, "we're not talking about making premium payments for those who enrolled, then fell behind, but only [for] first-time buyers," said Linda Quick of hospital group, which has not finalized its plans. The association would enlist local United Way chapters to find and enroll eligible residents.

Even so, Quick acknowledges that getting the program off the ground may be difficult because of the cost to hospitals.

"I have a couple of systems where we're talking about half a million dollars" in contributions, she said.

Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.