After eight months of searching for a job, Mary Nelson finally found one. The single mom, who is currently working to finish high school, now sells Harvard-branded sweatshirts, shot glasses and mugs at a mall in Boston.

Nelson, 20, got held back twice when she was younger, which meant she was 16 as a high school freshman. That was the last grade she completed.

She made the decision to get her high school diploma this year and started taking online classes through the Boston Public Schools Re-Engagement Center. The flexibility allows her to work, study and care for Maurice, her nine-month-old son.

"There was an option of getting my GED, and there's nothing wrong with that, but I want my son to see that I tried my best and I did my hardest for him -- and for myself as well," Nelson said.

Nelson is one of the many Boston students taking advantage of the vast number of programs available in the public school system. The city's dropout rate is 4.5%, one of the lowest of any major U.S. city, and it's been dropping for the last eight years.

One way Boston has tackled the dropout rate is to try to reach kids before they hit the point where Nelson once was. The city uses data to identify at-risk students as early as their freshman year, and some are flagged while still in the eighth grade.

"We can tell which students need which support," said Mary Skipper, network superintendent for Boston public high schools.

These students are identified through several factors, including poor grades and attendance, behavioral issues and family troubles. Often, kids just need extra time or more flexibility, and are offered enrollment in a five-year high school program.

It seems to be working. The graduation rate for Boston students taking part in the five-year program has been increasing over the last several years, and crucially, the additional year seems most beneficial to African-American and Hispanic students, who are most at risk.

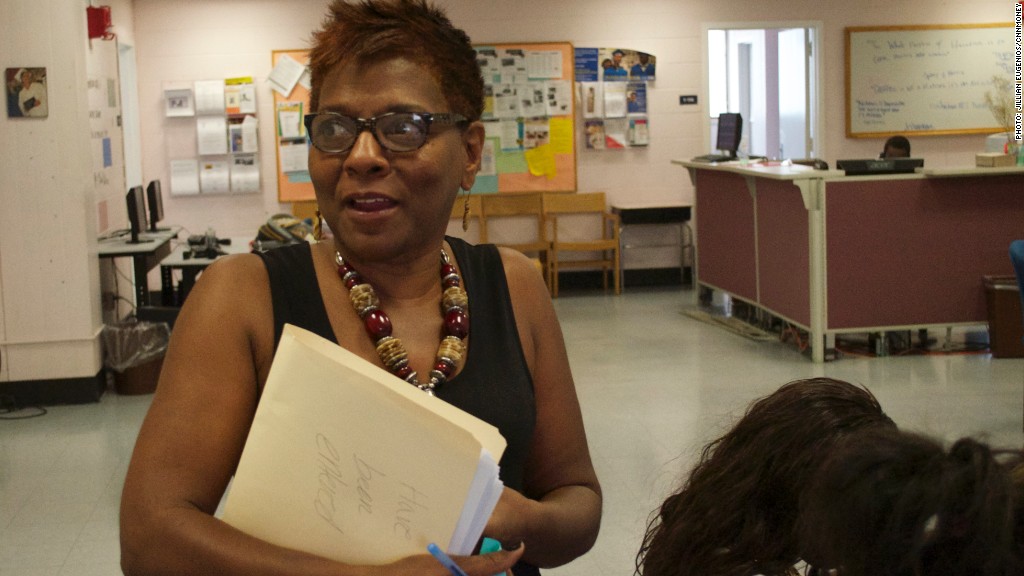

But kids still drop out, and the re-engagement center opened in 2009 to make sure they still have educational opportunities. It was only the second in the country (the first was in Philadelphia), and it identifies the best program for each student, whether it's regular high school classes, online courses or placement at Boston Adult Technical Academy, a public school for high school students ages 19-22.

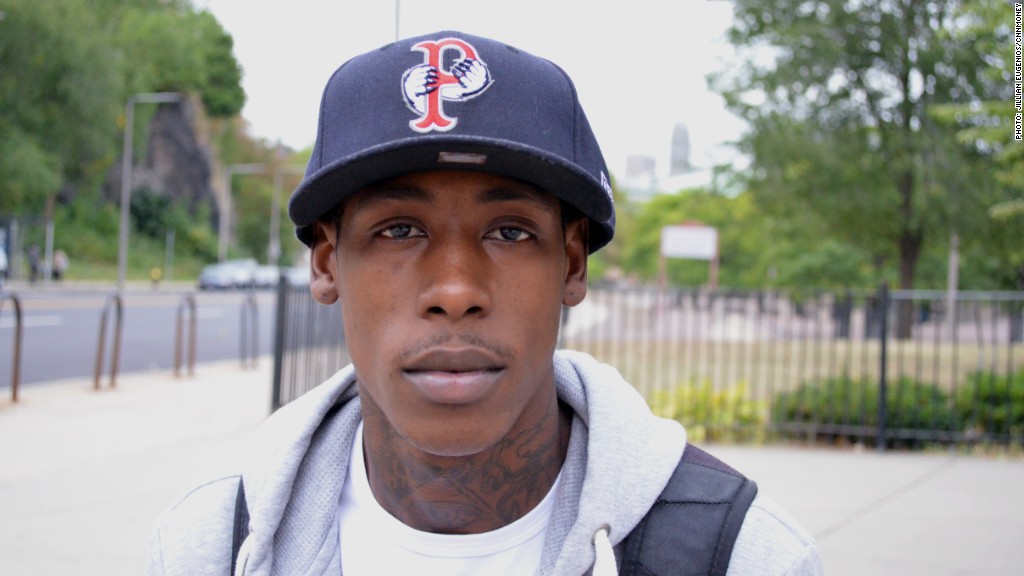

Hundreds of students make their way through the re-engagement center every year. Two years ago, Eugene Johnson, 22, was one of them. Like many kids, he was brought to the center by a friend.

He grew up across the street from Northeastern University, but never thought college was an option. He had a son at 16, dropped out of high school at 17 and spent the next several years homeless or incarcerated.

Then he made a decision to go back to school. "I just needed to complete some steps in my life," he said.

The center assigned him an academic counselor and matched his skill level with online classes. He spent two years at the center, going every day and even through the summers. He graduated a few months ago and has a home, a steady job and is studying to be a nursing assistant at a local community college.

"I'm not living for me," he said, and spoke of his son, now four years old. "I'm going to school for nursing for him. I can't have him going through what I just went through."

While Johnson's success is a win for Boston's school system, Skipper said the dropout rate still isn't low enough.

"Until it's at 0%, we as a district will not be satisfied," she said. "That is a Boston mentality."