"Put out the best, most honest newspaper you can today, and put out a better one the next day."

Every journalist can relate to those words, written by Ben Bradlee toward the end of his 1995 memoir "A Good Life."

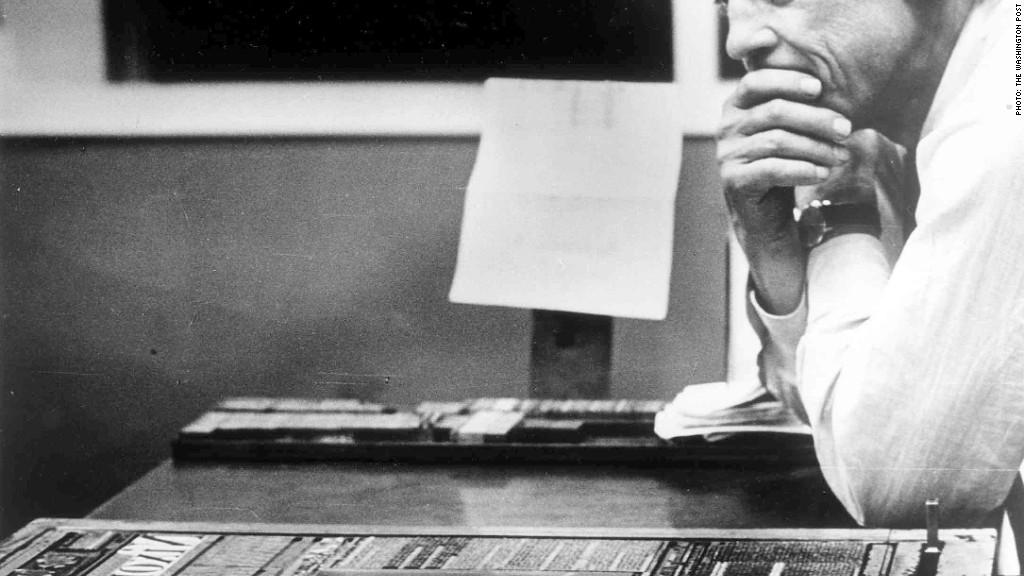

Bradlee, who died Tuesday at age 93, was the longest-serving top editor in the history of The Washington Post. He ran the newspaper with verve and determination from 1965 until 1991 and stayed closely associated with it for the rest of his life.

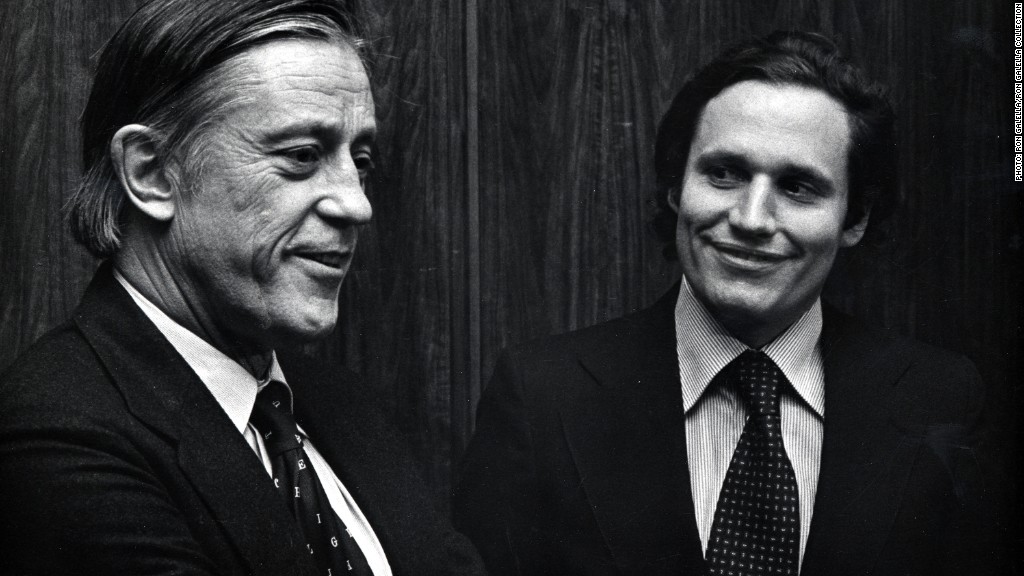

"He was the best," said Donald Graham, The Post's publisher during the latter half of Bradlee's tenure. "He pushed as hard as an editor can push to print the story of the Pentagon Papers; he led the team that broke the Watergate story. And he did much more."

In the outpouring of remembrances of the man, there's a sense that with his passing, an idea has died too, an idea about print journalism and impact and government accountability.

I think that's a premise that Bradlee would have ripped up.

As Graham said in a statement on Tuesday, Bradlee's "drive to make the paper better still breathes in every corner of today's Post newsroom."

Last year The Post was among the newspapers and web sites that turned Edward Snowden's cache of NSA documents into compelling stories about mass surveillance -- a clear example of "impact."

Still, it is worthwhile to reflect on what's changed, now that the notion of publishing "the best, most honest newspaper you can today" feels like it belongs to a prior generation.

David Remnick, once a young reporter for The Post and now the editor of The New Yorker, wrote that Bradlee ruled the newsroom "at a time before Craigslist, before newsroom cutbacks, before Politico, before the sullen loss of confidence," and before the Graham family sold The Post to Amazon (AMZN) CEO Jeff Bezos for an underwhelming $250 million.

Bradlee was on top when newspapers were on top.

"It is tough to imagine a newspaperman ever playing the kind of outsize role that he once did in Washington," wrote David Carr of The New York Times. "Newspapers, and people's regard for them, have shrunk since he ran The Post."

"What was great about Ben," wrote "This Town" author Mark Leibovich, "was that he embodied a much more confident time in American journalism -- before everyone was so terrified of offending readers, not giving them what they wanted, being accused of bias, not being sufficiently solicitous of the staff's feelings or constituency complaints or whatever grievance was trending on 'social media.'"

"Confidence" came up repeatedly in The Post's front-page obituary of Bradlee. Robert G. Kaiser, a 50-year veteran of The Post, started to write the obit 15 years ago.

Last week, coincidentally, Kaiser published "Bad News About The News," an essay for the Brookings Institution warning that "news as we know it is at risk" due to eroding business models in the digital age.

Some are more optimistic. There's a sense, as of late, that The Post is a revived force in reporting -- much attention has been paid to its recent scoops and to the fact that about 100 new employees have come aboard since Bezos bought the newspaper last year.

Amid all the tributes, a comment from Bob Woodward stood out. Woodward and Carl Bernstein led The Post's Watergate reporting while Bradlee led the editing, inspiring legions of young people to seek jobs in journalism in the 1970s and '80s.

Bradlee "was the editor of the 20th century," Woodward said. "His passing, in a way, marks the end of the 20th century."

Woodward said that to Politico, The Post's chief rival in Washington, a digital news operation created by two former Post reporters.

Bernstein, on CNN's "New Day" on Wednesday morning, said Bradlee "viewed the world like the young reporter he started as."

What might that young reporter say today?

"Put out the best, most honest home page you can this minute, and put out a better one the next."