Japan is suffering from an acute baby shortage.

Just slightly more than 1 million babies were born last year in Japan, according to new government figures. The tally is the lowest figure on record, and the latest sign that little progress is being made in the country's battle against unfavorable demographic trends.

Japan's health ministry also estimated that 1,269,000 people died in 2014, indicating a natural population decline of 268,000.

The country's shrinking population has raised alarm bells at the highest levels of government.

The trend threatens to severely limit economic growth as workers struggle to pay for the booming number of elderly.

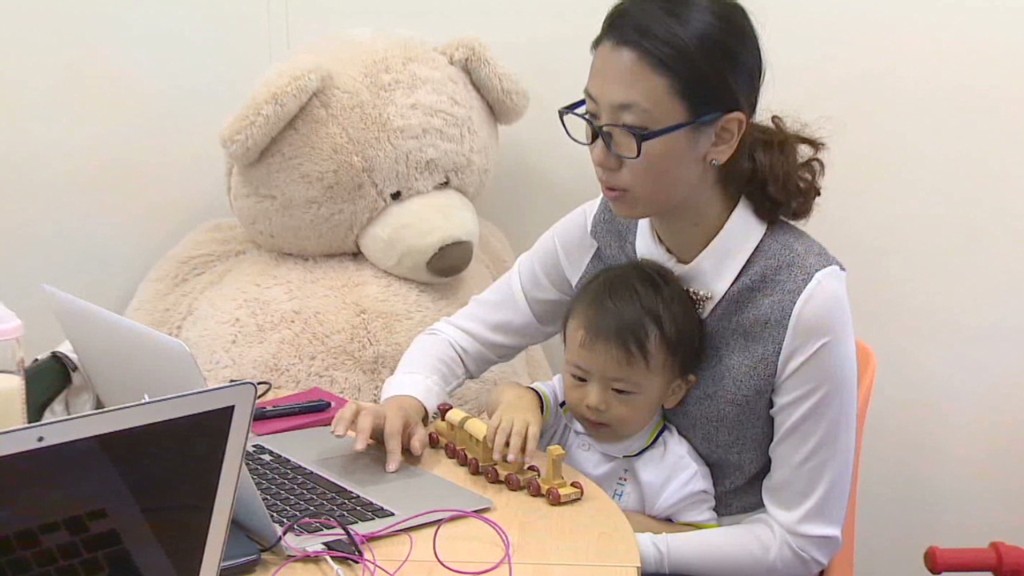

A trio of factors are to blame: The number of marriages has declined, corporate culture penalizes mothers, and Japan is notoriously adverse to immigration.

The most alarmist prediction suggests Japan's population could decline by a third over the next five decades.

The government has sought to boost births with reforms including more child care options for working mothers. The goal is to boost the number of births per woman to nearly 2.1 from the current 1.4 rate, but Tokyo has little to show for these efforts.

Related: Women hold key to fixing Japan's economy

The more obvious solution -- immigration -- remains the third rail of Japanese politics. Less than 2% of the country's population is foreign-born, and opinion polls indicate little support for more immigration.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has been walking a fine line on the issue, expressing support for broadening select immigration programs while failing to endorse more ambitious proposals.

If he were to advocate a stronger position on immigration, Abe would likely face stiff political resistance, especially in Japan's rural provinces.

Yet the timing could be right for Abe -- who recently secured a fresh electoral mandate -- to press the issue.

Jun Saito, a senior fellow at the Japan Center for Economic Research, has written that Japan is overdue for an honest conversation about immigration.

"We are ... being confronted with a choice between becoming a former economic power inhibited by mostly aged people, and becoming an active economic power where Japanese and foreigners live and work as partners," he said.

-- CNN's Junko Ogura contributed reporting from Tokyo.