In Europe, the new year is starting where the old year left off -- the euro is on the skids.

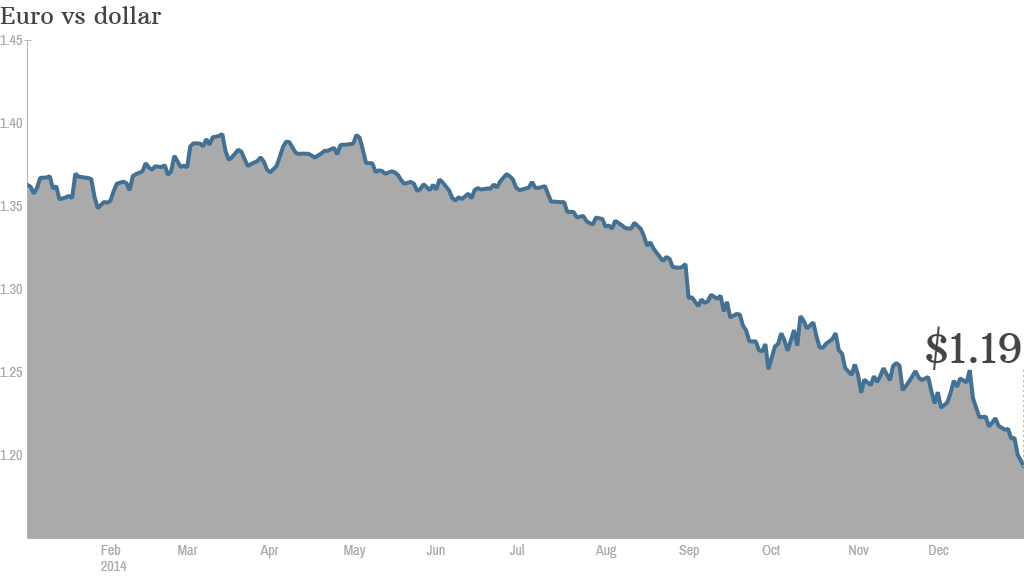

The currency briefly hit its lowest level against the U.S. dollar in nine years Monday, before steadying to trade around $1.19.

That leaves the euro down 20 cents, or about 14%, since May 2014. So why has it fallen out of favor so spectacularly?

1. The mighty dollar

Much of the recent decline in the euro has been about the strength of the greenback. During the second half of 2014, the U.S. dollar made significant gains against all other major global currencies, such as the British pound, Swiss franc and Japanese yen.

The U.S. economy is motoring, growing by 5% in the third quarter, and creating jobs at a rapid pace. That has allowed the Federal Reserve to end its emergency stimulus -- or quantitative easing -- and begin talking about when to raise interest rates from their record lows.

Compare that with the eurozone, where unemployment is stuck near record highs, the economy is stagnating and the risk of deflation looms large. Or Japan, where officials are going all in with stimulus.

2. European QE coming

Just as the Fed begins to tighten monetary policy, the European Central Bank looks poised to launch its own version of quantitative easing -- possibly as early as its next meeting on January 22 -- to head off the risk of deflation.

ECB President Mario Draghi passed up the chance of using the last big bazooka in the central bank's arsenal in December, saying he needed more time to assess the impact of the oil price slump on inflation, growth and wages.

The picture has darkened further since then, and ECB officials have been busy working on ways to launch a program of government bond purchases -- in effect printing euros in huge quantities.

The first estimate of December inflation in the eurozone, due Wednesday, could show a negative number -- recording regional deflation for the first time since the depths of the financial crisis.

Expectations of ECB action were heightened further Monday after Germany said inflation slumped to just 0.1% last month, a weaker number than analysts were expecting.

3. Greek fears grow

Adding to pressure on the euro is the risk that Greek elections on January 25 could revive the eurozone debt crisis.

Leading in the opinion polls is Syriza, an opposition party that wants to renegotiate the terms of Greece's 240 billion euro bailout by the EU and IMF -- including canceling part of its huge debt -- and reversing some painful austerity measures.

Germany, and others, will resist those demands. Giving ground to Athens could encourage other deeply indebted eurozone countries to insist on similar treatment.

Media reports suggest the German government could live with a Greek exit from the eurozone if it has to.

And there's been little sign of contagion so far. Yields on Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and Irish government bonds have held steady, while Greece's borrowing costs have spiked.

The most likely outcome is a messy compromise that is unlikely to enthuse investors.