The majority of children in America's public schools now are low-income. And that has major implications for the future of the nation's workforce.

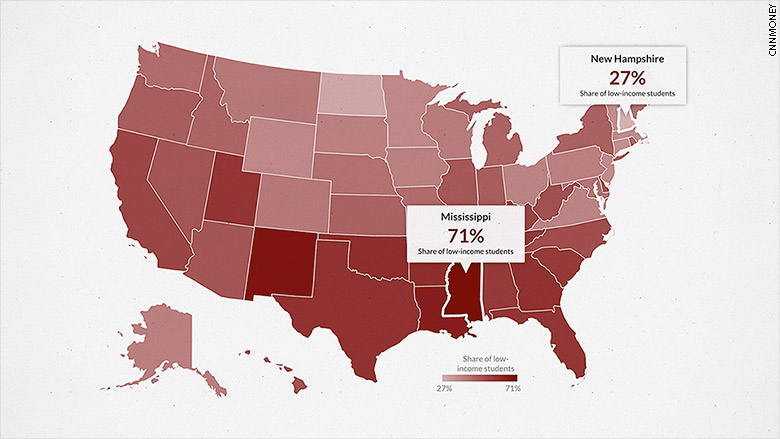

The share of schoolkids who qualify for free or reduced lunches crossed the 50% threshold in 2013, according to a recent Southern Education Foundation report. That compares to fewer than 32% back in 1989.

Students eligible for subsidized school lunches come from families who are in poverty or just above it. A child living with a single parent would qualify if the family's income was less than $28,000. A family of four would receive free or reduced lunches if their income was less than $42,600.

There are three main reasons behind the increase, said Steve Suitts, the report's author.

- Though the economy is recovering, it's not producing enough good-paying jobs to lift families into better financial situations.

- The growth in immigration is bringing more low-income children into the school system.

- Higher-income families are having fewer kids.

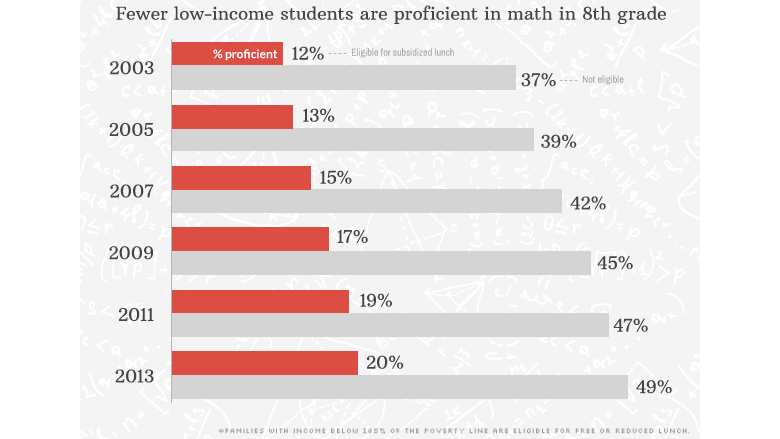

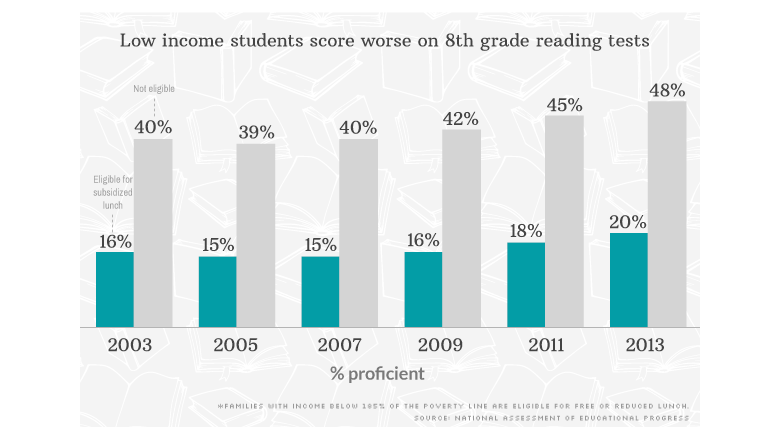

About 90% of America's children go to public school. Test scores clearly show that low-income students are far less proficient in math and reading than their better-off peers.

The gap hasn't really budged in a decade, Suitts said.

The divide is also clear in international educational measures.

American children who go to schools with fewer than 10% of students eligible for subsidized lunch score close to the top in math tests given to 15-year-olds, just behind China, Singapore and Taiwan. But kids in schools with 25% to 50% of peers in subsidized lunch fall about 16 rungs to the lower third of developed countries.

Related: States where taxes hit the poor hardest

That doesn't bode well for America's future, especially when these kids enter the job market.

"The nation's performance as a whole will decline until we assist low-income students to perform at higher levels," Suitts said. "These poorly educated adults are going into the workforce and the economy."

While employers increasingly look for more educated workers, students are increasingly leaving school with fewer qualifications. That skills gap will deepen the shortage of qualified job candidates, and keep the next generation from finding good positions, said Anthony Carnevale, director, Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

"It's a downward spiral of economic opportunity," he said.