In certain countries, Facebook is faced with a draconian dilemma: censor your posts or the company gets banned.

Consistently, it decides to censor.

This isn't about your photos or public messages violating Facebook's own rules, like posting pornography. This is Facebook (FB) acting as a government censor on that country's behalf.

It's worst in India, Turkey and Pakistan, where thousands of pages and photos get pulled down every year for "blasphemy," criticizing the government or posting something that's religiously offensive.

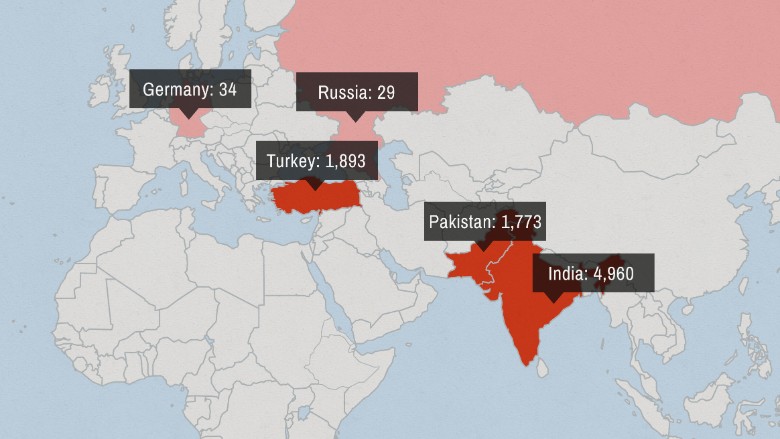

In the first half of last year, Facebook blocked nearly 5,000 "pieces of content" in India. There were nearly 2,000 taken down in Turkey and close to the same number in Pakistan.

You can still see those photos and comments outside of those countries. But they're nonexistent back home. It's selective blocking.

This information comes from Facebook itself, which keeps a running record on its public "Government Requests Report" website.

A recent incident in Turkey serves as an example of how this works. Following court orders in Turkey last week, Facebook blocked pages depicting the Muslim religious figure Mohammed.

It's not just developing nations that request Facebook to block access to posts. The list of places in which Facebook engages in this type of censorship includes nations typically viewed as more progressive: France, Germany and the United Kingdom.

Facebook generally portrays itself as a company that defends a user's ability to speak freely. In 2012, CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote to investors that the social media platform will help people's voices "increase in number and volume" and pressure political leaders to side with free speech.

And he specifically addressed the topic of Facebook playing government censor at a public question-and-answer session in Bogotá, Colombia last month.

"We want to give as many people as possible the ability to express as much as possible," Zuckerberg asserted -- but its free speech crusade only goes so far.

Zuckerberg said that when Facebook faces an ultimatum, it usually decides to abide by laws, even if they're oppressive. But it doesn't bow easily. Facebook's lawyers will fight and review every government demand carefully -- dragging their feet, and only narrowly abiding by a government's specific order.

For example, take the Russian government's arrest of Kremlin critic Alexey Navalny. The government demanded that Facebook take down an event page for a massive rally for Navalny. Facebook pushed back and eventually took it down -- but it kept up all the other copycat rally event pages.

"It becomes a very tricky calculus," Zuckerberg said. "I can't think of many examples in history where a company not operating or shutting down in a country in protest of a law like that who's actually changed the law."

Instead, Facebook wants to play the long game. The way Zuckerberg framed it: If it has to censor a little, but Facebook still increases communication over all, there's a net win. It's the same argument that's made when people say more liberal nations -- like the United States -- should do business with Cuba and China rather than shun them. Sure, more trade supports an oppressive regime, but there's hope that democracy and capitalism will spill over and help them in the long run.

But is Facebook just choosing money over morals?

In Bogotá, Zuckerberg asserted that "this is really about our mission and our philosophy, not... some short-term business decision."

But the company's message to investors says otherwise. In company filings with the Security and Exchange Commission last year, Facebook notes that it abides by local laws because the alternative -- getting banned outright -- "could substantially harm our business and financial results." If Facebook disappears in that country, a competitor will just swoop in and take its place.

And the pressure is on. In quarterly reports, India is repeatedly referred to as one of the "key sources of mobile growth." Facebook is only used by 10% of that country's 1.2 billion people. The space to grow is equivalent to three whole United States of America.

Why not take a stand? If you look at the number of Facebook users by country, nearly half of Turkey's 81 million people use it. Does Facebook really think the Turkish government can ban a service used by 38 million people and get away with it?

Actually, yes. Facebook pointed out to CNNMoney that Turkey already blocked Twitter and YouTube earlier this year. The threat is real.

So, until something changes, at a government's request Facebook will continue to silence Turks if they make fun of the nation's founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. And if Pakistanis point out the cozy relationship between the politicians and militant Islamist groups. And if Indians criticize a religion or the government.