Brazil looked like the next great economic growth story a few years ago, right after China. So how did things there get so bad, so fast?

Five years ago its economy grew three times faster than the United States. In 2011 its economic size surpassed Great Britain's. Millions of Brazilians moved from poverty to the middle class, and the president at the time, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, had an 83% approval rating.

Eike Batista, once Brazil's richest person, told "60 Minutes" that his nation was realizing its potential.

"Brazil has put its act together," Batista told 60 minutes in 2010. "We're walking into a phase of almost full employment...It's unbelievable."

It certainly was unbelievable.

Brazil's economy has had a dramatic fall from grace. The nation has been embroiled in a massive political scandal, it's seen a historic bankruptcy and is being led by an unpopular president, Dilma Rousseff, who is trying to preserve Brazil's economy.

Related: The 2015 bargain: emerging market stocks

"Brazil was in a better place five years ago." It missed the moment to improve its economy, says Paulo Sotero, director of the Brazil Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington. D.C.

The corruption case involving Brazilian oil and politicians has engulfed its economy in pessimism, experts say.

Brazilian investigators are unraveling a huge money laundering and bribery case centered around Petrobras (PBR), Brazil's state-owned oil company. Dozens of politicians, some in Rousseff's party, are accused of accepting millions in payments.

Related: Petrobras chief resigns amid corruption scandal

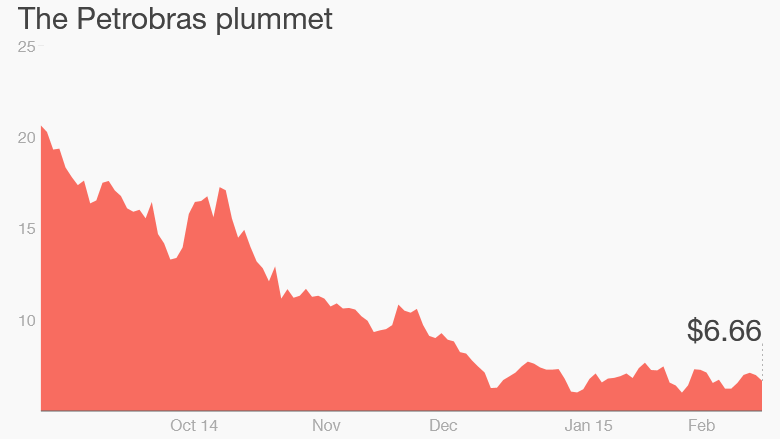

Petrobras has lost 60% of its market value since September. At the same time, Brazil's stock index, Bovespa, has plummeted too.

Government officials visiting New York on Wednesday tried to inject some positivity into the mess.

Joaquim Levy, Brazil's new finance minister, said that Petrobras is a transparent company.

"I'm very confident that they're going to overcome all the hurdles about their [bank] accounts," Levy said.

Brazil's political scandal is only the beginning of the nation's melodrama.

Batista, the billionaire who spoke to "60 Minutes," is bankrupt now.

Batista's oil company, OGX, filed for bankruptcy in October 2013, making it the largest corporate bankruptcy in Latin American history.

"Eike Batista sold that dream that there was this new gold rush there," says Fernando Lara, chair of the Brazil Center at the University of Texas--Austin. "The story of OGX and Batista represents the fictional side of the [economic] boom."

Related: Brazilian stocks take beating after election

Batista now owes over a billion dollars, giving him the rare title of "negative billionaire." He's in court on insider trading charges and police raided his home last week and seized all his assets.

Batista once had ties with President Rousseff, who is fighting her own uphill battle: reviving the economy.

President Dilma Rousseff has barely held on to power.

Rousseff narrowly won re-election and promised economic reforms. But reform won't be easy.

Her approval rating is 23%, according to Datafolha, a Brazilian poll.

The troubles have shaken the public's confidence in the government and in the economy.

Related: Rio 2016 organizers slammed over Olympic preparations

"There is a pessimism in general, and that pessimism surely has had a big impact on the stock market," says Fernando Lara, chair of the Brazil Center at the University of Texas--Austin. "Petrobras is a part of that pessimism."

A boom for commodities had propelled Brazil's economy. Now the price for many of Brazil's key exports, like oil and soybeans, has fallen due to declining demand from China, Brazil's biggest trade partner.

Brazil's currency, the Real, is losing value too. One U.S. dollar was worth about 1.55 Brazilian Reals shortly after Rousseff took office in 2011. Now one dollar equals 2.80 Reals, a concerning sign for a country plagued by hyperinflation during the 1980s and 1990s.

Many experts see Brazil eventually emerging from its current economic turmoil but they say the next few years will be rocky for Rousseff and Brazil.

"It means a couple of years that might be a little bit unpleasant," says Harold Trinkunas, a Latin American expert at the Brookings Institution. The government, "can see the slowdown coming at them."