When Tom Hanks and Sam Shepard need to get their typewriters fixed, they know exactly where to go: Gramercy Typewriter, a third-generation, family-run shop that's still click-clacking away after 83 years.

Yes, the typewriter is an anachronism. But no, it has not gone extinct. Nor have the typewriter repairmen of Manhattan, who labor endlessly to keep all those Smith-Coronas and IBM electrics running.

"I'm one of the last of the Mohicans," said Paul Schweitzer, who owns Gramercy Typewriter with his son Justin and has been repairing the machines for 55 years. "It's nice being needed by customers and I enjoy what I do."

Yes, needed. Because during a recent visit to the Schweitzers' shop -- which has been located in the shadow of the Flatiron Building for 47 years -- the phone was ringing off the hook.

That's because there are still many offices in New York City that continue to use dozens of typewriters and also a devoted group of fans like Tom Hanks, who use the typewriter on a regular basis.

But there are only two or three repair shops left in New York to fix those clunkers when a key stops working or a ribbon needs changing.

Like the rows of typewriters in their shop, the Schweitzers represent a different era -- donning suits and ties to work every day and filing out work orders in handwriting. There's no email or credit cards in the store. Customers have to pay by cash or check.

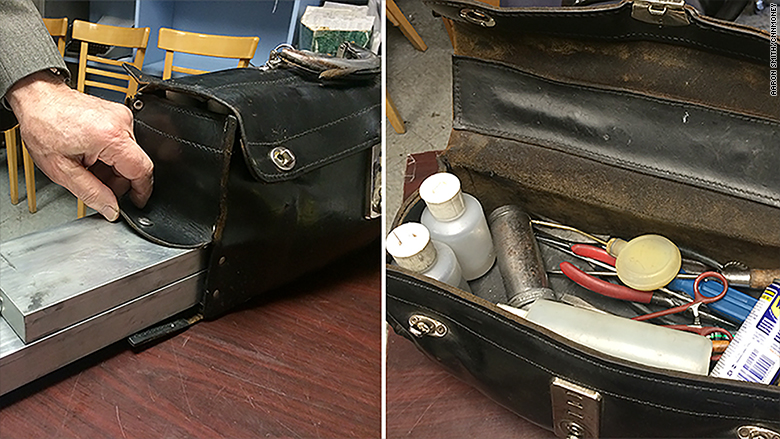

And the duo are accompanied on office calls by an old fashioned doctor's black bag outfitted with metal drawers that contain all sorts of spare parts, screwdrivers and pliers.

There's always a lot to do. The Schweitzers find it inconceivable that they'll ever run out of jobs in this antiquated line of work that has become all but obsolete with the advent of the computer.

"There's plenty of work every day," says Justin Schweitzer, the grandson of the founder who works six or seven days a week to whittle away the backlog. "We never catch up."

The Schweitzers cater to venerable writers like Gay Talese and Nat Hentoff, and companies like Barnes and Noble (BKS), PricewaterhouseCoopers and the law firm Vedder Price. Some offices still use typewriters because they're handy for filling out printed forms and continue to employ a group of trusty hands that refuse to give them up.

Some professional scribes prefer typewriters over computers to get rid of distractions like the Internet. Some writers, like Hanks, prefer the sound and cadence of the old writing machines.

The Schweitzers also sell supplies like ribbon, which is manufactured by a small business in New York City. Over the years, they've amassed typewriters in their office and Long Island homes which they "cannibalize" for parts when needed.

They also sell refurbished models and their shop is piled high with them.

Their oldest models are a Corona from 1917 and an Underwood, circa 1918 to 1920. The bulk of their machines are from the period between the 1940s and the 1960s. Their newest typewriters are electric models from the 1970s.

There was a period when business was down and the Schweitzers supplemented their typewriter repair business by selling and repairing H (HPQ)Laser Jet printers in the early 1990s. That became the bulk of what they did until a few years ago when they started inheriting the business of other retiring repairmen, like Bino Gan of Typewriters 'N Things, who used to repair typewriters for Woody Allen and Francis Ford Coppola before retiring last year.

Now the Schweitzers' work is again dominated by typewriter repair. The repair costs vary widely, where refurbishing one with hard-to-find parts can cost as much as $500.

Paul Schweitzer said the bulk of his work is making office calls, were he cleans, maintains and repairs the machines.

His father, Abraham, started the business in the Gramercy neighborhood in 1932, when the country was gripped by the Great Depression. He made office calls and found plenty of work because "every desk in every office had a typewriter," said Paul. The patriarch stuck with it until 1974, when Paul took over the business.

Paul, who is now 76 years old, started working with his father in 1959 after a three-year stint in the Navy. He said he was back home in Brooklyn for only two days when his father said, "'Well, what are you doing? Get to work.' I said, 'I'll give it a try until I figure out what I'm going to do.'"

Paul told this story on a recent weekday morning, as he prepped for an office call by suiting up and grabbing his black leather bag of spare parts and tools.

"Well, here I am, 55 years later, still trying to figure out what I'm going to do!" he laughed.