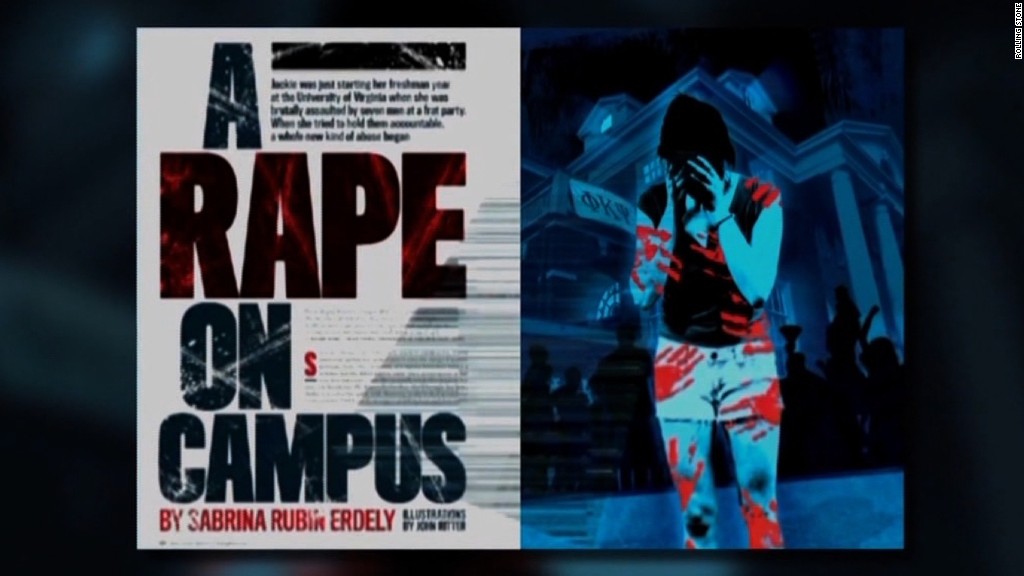

An institutional failure at Rolling Stone resulted in a deeply flawed article about a purported gang rape at the University of Virginia, according to an outside review by Columbia Journalism School professors.

The review, published Sunday night, says the failures were sweeping and "may have spread the idea that many women invent rape allegations."

At the same time the review came out, Rolling Stone officially retracted the story and said sorry. But the publisher, Jann Wenner, has decided not to fire anyone on staff. He believes the missteps were unintentional, not purposefully deceitful.

One thing is clear: All of this could have been avoided if the writer, Sabrina Rubin Erdely, had made more phone calls.

"The editors invested Rolling Stone's reputation in a single source," Columbia's 12,866-word report concludes.

The source was Jackie, a student who leveled allegations of a violent gang rape against a group of fraternity students. None of her allegations have been corroborated.

Columbia's report says "if Jackie was attacked and, if so, by whom, cannot be established definitively from the evidence available."

Charlottesville police recently announced they could find no evidence that a rape occurred. But they stressed that their findings did not mean that she hadn't been raped and that they were keeping the investigation open.

Jackie did not cooperate with either the police investigation or Columbia's. Her lawyer told Columbia that it is "in her best interest to remain silent at this time."

Related: How the Rolling Stone article became a national issue

Columbia's behind-the-scenes account is embarrassing for all involved. Rolling Stone failed several lessons from Journalism 101.

Sean Woods, the primary editor, "did not do enough" to press Erdely to "close the gaps in her reporting," the report says. And Will Dana, the magazine's top editor, "might have looked more deeply into the story drafts he read, spotted the reporting gaps and insisted that they be fixed. He did not."

Erdely, a freelance writer, issued a formal apology on Sunday night. So did Dana.

Magazine commits to Columbia's recommendations

"We are officially retracting 'A Rape on Campus,'" Dana said in an editor's letter. "We are also committing ourselves to a series of recommendations about journalistic practices that are spelled out in the report."

Those recommendations included little or no future use of pseudonyms and greater efforts to check "derogatory information."

Dana also said "we would like to apologize to our readers and to all of those who were damaged by our story and the ensuing fallout, including members of the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity and UVA administrators and students."

Teresa Sullivan, the president of UVA, issued a statement Sunday evening that described the magazine's story as "irresponsible," saying it "did nothing to combat sexual violence, and it damaged serious efforts to address the issue."

The fraternity is considering suing Rolling Stone; a spokesman said the frat may have more to say on Monday.

Related: Reactions at UVA: 'Rolling Stone didn't do its job'

The specter of legal action may explain why Columbia says "Erdely and the editors involved declined to answer questions about the specifics of the legal review" of the story, "citing instructions from the magazine's outside counsel."

Rolling Stone had asked Columbia University's Graduate School of Journalism in December to conduct the external review.

Columbia embraced the challenge. Its review identifies three main failures, with the "most consequential" one being that Erdely did not interview the three friends who were with Jackie the night she says she was raped.

The "Rape on Campus" story did quote them, but those quotes were based on Jackie's recollection of conversations they shared, not based on any other interviews.

"That was the reporting path, if taken, that would have almost certainly led the magazine's editors to change plans," Columbia's investigators say.

When other news organizations, including CNN, spoke to the trio, it became clear that there were many inconsistencies in Jackie's story. For instance, the friends said Jackie did not appear bloody or beaten after the alleged attack.

The friends told Columbia that they would have talked to Rolling Stone if they'd been contacted. But they weren't.

Students say writer had an agenda

"It just goes to show that she likely operated with some kind of agenda," said one of the three, Alex Stock, "because she was looking for a story and it didn't matter if it was true or not."

After the report was published on Sunday night, he said, "At first I didn't know, but now I think it's devastatingly clear she didn't do her research at all."

Another one of the three friends, Ryan Duffin, said Erdely "thought Jackie had contacted us and we had said no to an interview." Duffin told CNN he agreed with Columbia's conclusion that more thorough reporting by Erdely would have changed the outcome.

"Had she gotten in direct contact with us, it probably wouldn't have been printed, at least in that way," he said. "A lot of the article was still based in truth, but the focal point would have been different."

Erdely told Columbia that "in retrospect, I wish somebody had pushed me harder" about reaching out to the three friends.

But her editor, Woods, told Columbia that he did push: "I did repeatedly ask, 'Can we reach these people? Can we?' And I was told no."

Beyond the three friends, the report faults Erdely with not sharing more information with the accused fraternity ahead of time. If she had, the frat would have probably alerted her to factual discrepancies, and that "might have led Erdely and her editors to try to verify Jackie's account more thoroughly."

The report also faults Erdely and Woods with not trying harder to track down the alleged ringleader of the gang rape. Jackie gave Erdely the silent treatment while Erdely tried, so the magazine eventually "capitulated," apparently fearing that their primary source would stop cooperating.

Fundamentally, Erdely and the editors were over-reliant on Jackie and insufficiently skeptical the whole way through.

Even Wenner, when he read a draft of the story, told Columbia that he found Jackie's case "extremely strong, powerful, provocative... I thought we had something really good there."

A spokesperson for Wenner told CNN that Erdely will continue to write for Rolling Stone.