A computer security expert was pulled from his United Airlines flight in Syracuse on Wednesday afternoon, after the FBI feared he had hacked the plane.

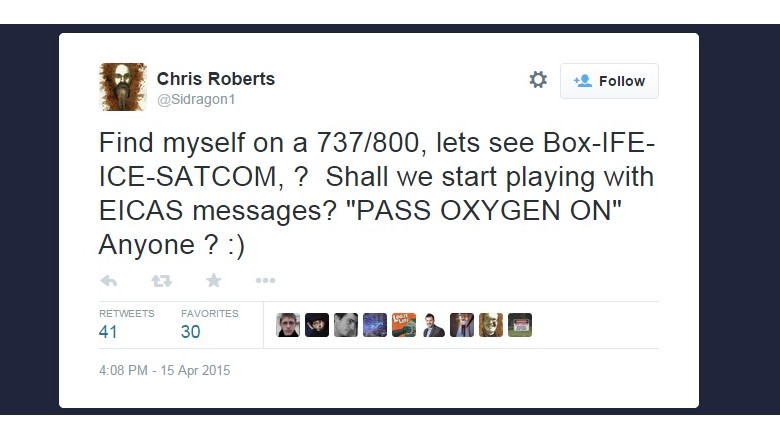

All it took was a tweet to raise the FBI's suspicion.

It sounded like Chris Roberts, a cybersecurity professional from Denver, was about to use his laptop to force the plane to deploy the emergency oxygen masks.

In a tweet, Roberts referenced the plane's satellite communications and the aircraft's engine-indicating and crew-alerting system.

Federal law enforcement didn't find that funny and immediately kicked into action. Roberts said FBI agents detained and questioned him for four hours. They also seized his laptop, iPad, hard drives, and other computer gear.

A day and a half later, it's clear that Roberts meant no harm. The plane is fine. No one was hurt. The computer gear should soon be on its way back to Denver. And Roberts learned to be more careful on Twitter.

But this ordeal also reveals a potentially dangerous flaw in airplanes. Roberts said he took to Twitter out of frustration that Airbus and Boeing (BA) - the world's two largest plane manufacturers -- aren't listening to warnings he's made for years.

Anyone can plug a laptop into the box underneath his or her seat and reach key controls in the plane, such as engines and cabin lighting. That's the claim made by Roberts and the cybersecurity firm he co-founded, One World Labs.

"I was probably a little more blunt than I should have been," Roberts told CNNMoney. "I'm just so frustrated that nothing is getting fixed."

United (UAL) deferred all questions to the FBI. The agency has not yet provided comment on the matter.

He hacks planes?

Roberts' job is to find weaknesses in computer systems -- especially airplanes. For years, he explored whether a malicious hacker could take over a pilot's controls -- and how they'd do it.

He found that a hacker could theoretically do it from a passenger seat. Every chair has a tiny computer and screen, and those are plugged into the airplane's CAN bus. Every vehicle has one. Think of it like a spine. It's how the brain communicates with the limbs. It's how your car accelerator talks to your engine's fuel injector.

But -- if it's not built just right -- it also means your plane passenger seat is ultimately connected to the pilot's cockpit.

Roberts said he eventually tested out the theory himself 15 to 20 times on actual flights. He'd pull out his laptop, connect it to the box underneath his seat, and view sensitive data from the avionics control systems.

"I could see the fuel rebalancing, thrust control system, flight management system, the state of controllers," he said.

If a fellow passenger ever asked what he was doing, Roberts would simply say, "We're enhancing your experience by putting in new systems."

Roberts is adamant that he never tried to take control of these things. But he grew increasingly worried that this flaw existed.

One World Labs said it repeatedly warned AirBus and Boeing in recent years about the danger in connected computer networks. Roberts said their response to him has been the same: "We'll deal with it later. We don't have time. We have other projects."

Airbus and Boeing did not return CNNMoney's calls for comment. But they have released relevant statements about the subject following a recent report by the Government Accountability Office that says newer aircraft are vulnerable to hacking.

Both companies said there are security measures in place (such as firewalls that restrict access). Airbus said it "constantly assesses and revisits the system architecture" to make sure planes are safe. Boeing also noted that pilots rely on more than one navigation system -- so even if a hacker disrupts one of them, pilots can still rely on others make safe decisions overall.

One World Labs tried a different approach earlier this year, when it instead disclosed these flaws to the FBI and a U.S. intelligence agency. Mark Turnage, the firm's CEO, said they met with two FBI agents in Denver on several occasions -- and was told to never hook up his laptop to a plane again.

Hence, why his message on Twitter -- which referenced toying with the planet's satellite communication link -- didn't go over so well.

Was he too aggressive?

"Yeah," Roberts said. "Do I occasionally nudge the rules? Damn right I do. If not, I wouldn't do the research I do."