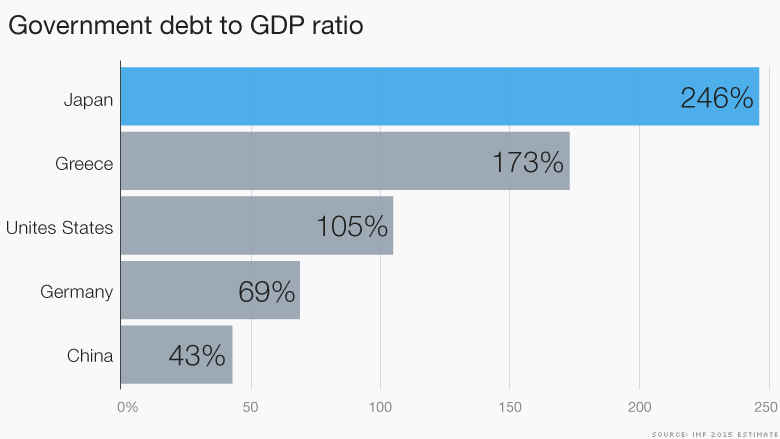

The crisis in Greece is coming to a head.

A self-imposed deadline for the Greek government to strike a deal with its creditors passed Sunday, and it faces several big payments this month.

Here is how the crisis could play out, and lead to a Greek exit (Grexit) from the euro:

Crunch time

Greecec can't borrow from international bond markets and urgently needs the last tranche of its 240 billion euro ($262 billion) bailout so it can pay its bills. Europe and the International Monetary Fund will only release the final 7.2 billion euros if the anti-austerity government agrees to economic reforms.

The clock is ticking -- the bailout expires at the end of June, after which Greece would be on its own financially. A last minute deal is always possible, despite the apparent gulf between the two sides, but economists say the risk of failure is rising.

Athens only managed to stay afloat last month by raiding its emergency reserves, and forcing local government and other public bodies to hand over cash.

Related: These investors are getting killed in Greece

Payments loom

Greece needs to pay the IMF nearly 1.6 billion euros ($1.75 billion) in June -- starting with 300 million on Friday. It may be allowed to delay this week's payment until later in the month.

But state pensions and salaries worth about 1.7 billion euros also fall due towards the end of June. The Greek government has said that it would prioritize pensions over payments to the IMF.

The IMF is the world's lender of last resort. If Greece doesn't meet its IMF commitments, it won't be able to borrow money anywhere else. No developed economy has ever missed an IMF payment.

Banks

Failure to pay the IMF would likely trigger a run on Greek banks by depositors worried that their cash may lose value if Greece is forced to leave the euro. The banks have already seen hefty withdrawals this year due to the continuing standoff between Athens and its creditors.

Emergency financial assistance from the European Central Bank is the only thing keeping the banks afloat. In the absence of a bailout agreement, the ECB will not throw more money into the system.

Greece would then be forced to consider shutting its banks for an extended period -- as Cyprus did two years ago -- to limit the damage. That could buy time for new crisis talks, or for the government to set limits on how much cash Greeks could withdraw from their accounts or take out of the country.

7 reasons Grexit wouldn't be a total disaster

Parallel currency

Greece might be able to cling on to the euro even amid this horror scenario. It could issue IOUs -- effectively a parallel currency to the euro -- to pay wages and other domestic commitments, allowing the government to use scarce euros to meets its international interest payments.

These "I Owe You" notes have been used in the past to help governments get over a temporary shortage of cash, for example by California in 2009.

No more euros

But at some point, those notes would need to be converted to cash -- and that's when Athens may have to abandon the euro and print its own money.

Analysts at Moody's say Greece would only drop the euro and issue its own currency if there was absolutely no other alternative.

It is likely the new currency would quickly lose its value. While that would be painful at first, it could eventually help Greece back on its feet. A cheaper currency would make Greece more competitive and attractive for investors and tourists.