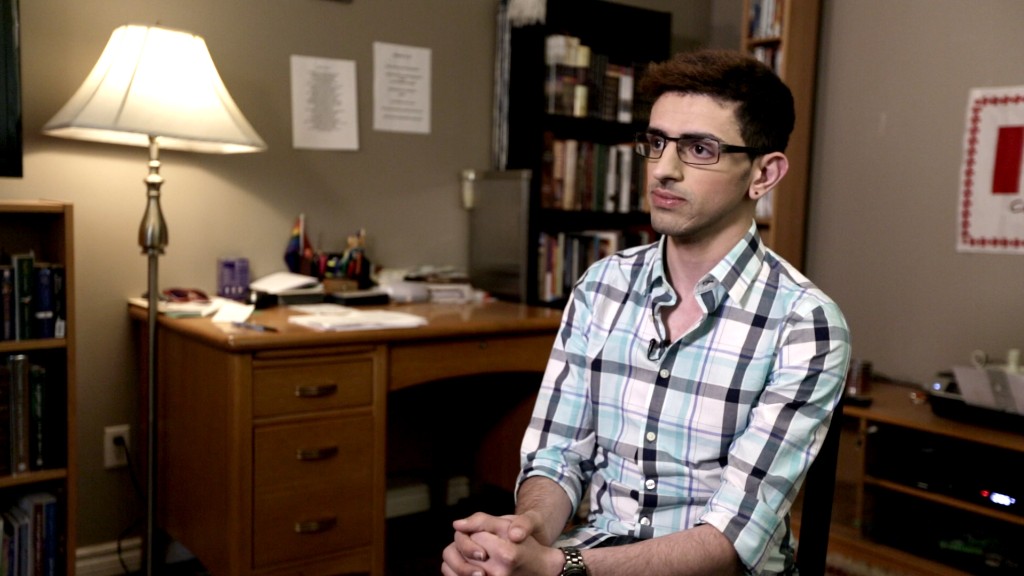

John Calvin is a seemingly normal 24-year-old. He poses in selfies on Facebook and chats with his friends over Snapchat. He lives in Edmonton, Canada, and attends church regularly.

But here's what makes him different: Calvin, who is also gay, comes from a family with ties to Hamas and is facing deportation on Nov. 4 -- what he says will be a "certain death."

Calvin, who changed his name several years ago to protect his identity, identifies his grandfather as Said Bilal, one of the founding members of Hamas. His uncles have been linked to several suicide bombings, according to the Israeli authorities.

"Islam [and] Hamas were the two things that my family revolved around," Calvin said. "It was not part of my family's identity. It was the identity we had."

But growing up in the West Bank, Calvin says he was unlike other members of his family. He was fascinated by Dan Brown's "The Da Vinci Code" and began exploring Christianity. He liked men from an early age. And at 14, Calvin says he began questioning his upbringing.

He fled to Israel where he was imprisoned for illegally crossing the border. There, he says he was sexually assaulted by a man from his hometown.

Calvin says he'd been taught to hate Jews, but after the attack, Israeli prison guards showed him compassion.

"That was the moment when I started breaking off from my beliefs," he recalls.

When he returned home, Calvin says he faced violence after his family learned that he wanted to convert to Christianity.

"My father ... actually planned it so I was to be put to death," he told CNNMoney.

Calvin said his mother broke down and told him of the planned "honor killing," after which he fled to Canada, where he received a student visa and applied for refugee status in 2011.

He spent the next four years building a new life -- he met friends who became his new family. He studied Bible and theology, and became an active member of the Christian community in Edmonton. From the safety of Canada, he says he called home to tell his parents he was gay.

But on New Year's Eve, he learned he could lose his safe haven. His refugee application was denied. The notice from the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Board cited Calvin's links to Hamas. Just weeks ago, he received his deportation date: Nov. 4.

The notice found him to be a contributing member of Hamas, citing Calvin's immigration interview where he disclosed that his family had given him a gun as teenager, although he says it was never used. It also cited his disclosure that he had carried messages between family members

Calvin's attorney Nathan Whitling says he shouldn't be held accountable for his actions as teenager.

"He was just simply running errands for the senior members of his family," he told CNNMoney. "He certainly wasn't involved in any actual acts of terror."

But even so, the notice said he had been a member of Hamas. (It said he became a de facto member because he was born into the organization, but at 14, he had the mental capacity to understand his family's wrongdoings).

Calvin says if he's sent home, his life will be in jeopardy given his faith, his sexuality, and his family's ties to Hamas.

CNNMoney contacted Calvin's father, Jehad Salameh, who denied that he'd planned to kill his son in the past. When asked about his son being gay, Salameh said his son was sick, and if he returned to the West Bank, he'd take him to the doctor. He went on to say his son was schizophrenic.

"Islam never imposes punishment on a mentally ill person," he said when asked if Calvin would face harm upon returning.

But in another conversation, Salameh painted a different picture.

Salameh likened Calvin's possible return to the death of Saddam Hussein's son-in-law, Hussein Kamel, who defected and was eventually killed by people in the community.

"Our family is no less dignified than Saddam Hussein's family," Salameh told CNNMoney in a phone interview. "His fate may not be different than that traitor general Hussein Kamel."

"What he did is offensive to honor and to religion," Salameh added. "And the family has the right to retaliate against him."

The Canadian government would not comment specifically on Calvin's case but said the decision to remove someone from the country is not taken lightly.

Since Canada has designated him a former member of a terrorist organization, Calvin can't appeal the denial or claim refugee status in Canada, Whitling said.

So his options are limited.

His only recourse is to apply for a risk assessment, which determines whether his life will be in danger or he'll face punishment upon returning, said attorney Bjorn Harsanyi, who is working with Calvin.

Even if he's found to be a person in need of protection, Calvin will be in a form of "immigration limbo," Harsanyi said. "You're allowed to stay [in Canada], but it's not the same. ... He can't vote, it'd be difficult to travel, difficult to get a driver's license."

For Calvin, it's a waiting game. He's currently looking to seek asylum in Europe and the United States. To seek asylum in the U.S, his best bet is to find his way to a U.S. embassy (likely in Israel or Jordan) once he's sent back, a U.S. official told CNNMoney.

For now, Calvin is working on completing his risk assessment and applying for a ministerial exception that would allow him to seek permanent residence in Canada even though he's been determined a former member of a terrorist organization.

"The government has the power to lift the impediment by granting an exemption," Harsanyi says, adding very few have been granted.

Harsanyi says the case sends a message to anyone looking to follow in Calvin's footsteps.

"It will simply discourage other like-minded individuals from leaving these organizations because they will have nowhere to turn for safety," he said.