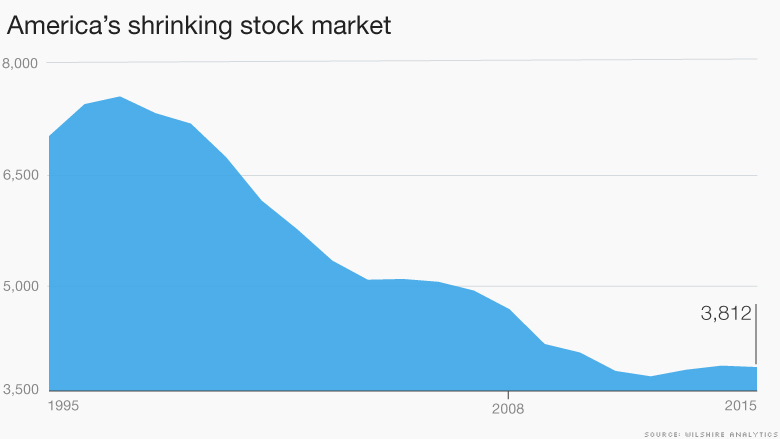

Believe it or not, the U.S. stock market had way more companies back when Mark McGwire was chasing homerun records.

The number of publicly listed U.S. stocks peaked at a record 7,562 during McGwire's record-setting summer of 1998, according to the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index. Today, there are just 3,812.

So what gives? Simply put, there are more companies disappearing than entering the stock market.

This isn't a trivial problem that only matters to bankers on Wall Street. Not only do investors have fewer options to invest in, but it directly impacts American jobs.

Related: The next domino to fall: Latin America

"We're shrinking the stock market. Unless we figure out how to create a lot more startups and a lot more IPOs, the economy is going to continue to generate jobs at lower rates than it should," said David Weild, former vice chairman at Nasdaq who has testified in Congress about capital markets.

How did we get here? It's important to note that the collective value -- known as market capitalization -- of the stock market has risen tremendously since the 1990s. However, the number of stocks in the market peaked in July 1998, just as companies were racing to go public in the Internet boom.

"There was this myth that if you could start a company and put dot-com in the name you would become instantly rich," said Bob Waid, managing director of Wilshire Analytics, which oversees the Wilshire 5000.

Obviously, they were wrong. Going out of business is one way companies get delisted from the market.

Related: IMF warns U.S.: Your financial system is (still) vulnerable

IPOs can't keep up with M&A: The other way is through mergers and acquisitions, which cause one stock to stop trading as it's absorbed by another company. The M&A market is booming: A record $1.1 trillion of U.S. deals were done during the first half of 2015, according to Dealogic.

In a perfect world, delistings are offset by the creation of new public companies through IPOs, or initial public offerings. Yet the IPO market hasn't rebounded to its dot-com era levels.

Back in 1996, an incredible 848 companies went public, raising a total of $78.6 billion, according to Dealogic. In 2014, the IPO market did $96 billion of deals last year, but only 292 companies went public.

One explanation for the IPO decline is the presence of other sources of capital, including venture capital and private-equity firms. Startups like Uber and Airbnb are raising gobs of money in the pre-IPO market, which some fear looks like a bubble.

Other startups may be discouraged from going public by regulation. Costly disclosure and other requirements in Sarbanes-Oxley have lessened the appeal of the IPO route.

Related: Who will get hurt if the startup bubble bursts?

Startup world is shrinking, too: The other explanation is that there are simply fewer young companies in the U.S. Startups made up almost 15% of all U.S. companies in 1978, compared with just 8% in 2011, according to Brookings Institute research.

"We've had a massive collapse in the number of startups. That's where job growth occurs," said Weild.

Weild blames major changes to market structure in the late 1990s and early 2000s that have disadvantaged small-cap stocks (like startups) against large-cap ones like IBM (IBM) and Microsoft (MSFT).

For example, Nasdaq's (NDAQ) decision to become a for-profit corporation has shifted its objectives. Weild said the exchange no longer advocates for the ecosystem of small investment banks that previously supported small-cap stocks.

Likewise, Regulation ATS in 1998 ushered in the widespread use of electronic markets in the U.S., making trading far more efficient and cheaper for everyday investors. However, Weild argues it also made it less profitable for the small investment banks, many of which no longer exist.

Related: NYSE suffers four-hour trading outage

Venture exchanges: So what's the solution? Weild and others have pushed Congress to create so-called "venture exchanges" that would cater to young companies. In theory, these exchanges would help the economy by giving startups access to capital that they aren't getting from the current market structure.

"We've created a market structure in the United States that's really undermined our future. If you shut down your ability to start small companies, you also inhibit your ability to create large ones," Weild said.