Greece avoided a catastrophic exit from the euro with this week's bailout deal, but there's still plenty more pain to come.

Shattered business confidence, a three-week bank shutdown and capital controls have already guaranteed another year of recession in 2015. That means the economy will have contracted for seven of the last eight years.

The European Commission says Greek GDP may shrink by as much as 4% this year, especially since banks have been limiting cash withdrawals during the country's vital tourist season. Some private forecasters are predicting an even bigger fall. And the economy may not see growth again until 2017.

Greece has begun implementing painful tax rises and spending cuts, which were conditions set by creditors to get a new bunch of bailout loans worth up to $96 billion. And that new bailout will add to the country's already enormous debt burden.

It all combines to form a bleak outlook for an economy that has shrunk by 26% since the start of the crisis. Here's how things could deteriorate further:

1. Cash controls hurt

The European Commission is now forecasting Greek GDP to fall by up to 4% in 2015, compared with growth of 0.5% it predicted earlier this year. Next year, the economy could shrink by as much as 1.75%, it said, and Greece won't see a return to growth until 2017.

The country's banking system is effectively paralyzed after the government introduced capital controls nearly three weeks ago.

The financial shutdown has hobbled the economy. Since June 28, Greeks have been able to withdraw only 60 euros per day, leaving businesses and consumers with very little cash to pay for goods and services during the crucial summer tourist season. Some public services have stopped charging customers.

Oxford Economics said Greek GDP could decline by as much as 5% over the next 12 months if capital controls aren't lifted soon.

"The combination of capital controls and austerity looks like being a particularly toxic mix that has the potential for an ugly negative feedback loop," said chief European economist James Nixon.

Related: Greek crisis a summer tourism killer

2. Austerity hits demand, jobs

Greece has endured years of austerity already, as it has tried to bring government borrowing under control, and restore competitiveness to its economy.

Tentative signs of recovery were in the cards in 2014 -- when Greece was actually growing -- but months of uncertainty this year, and the turmoil of recent weeks means it now finds itself in an even deeper financial hole.

This means more tax hikes and reforms that, at least in the short term, could further hit spending and trigger more job losses. Lawmakers have already approved hikes to sales tax on restaurant meals and other items, for example.

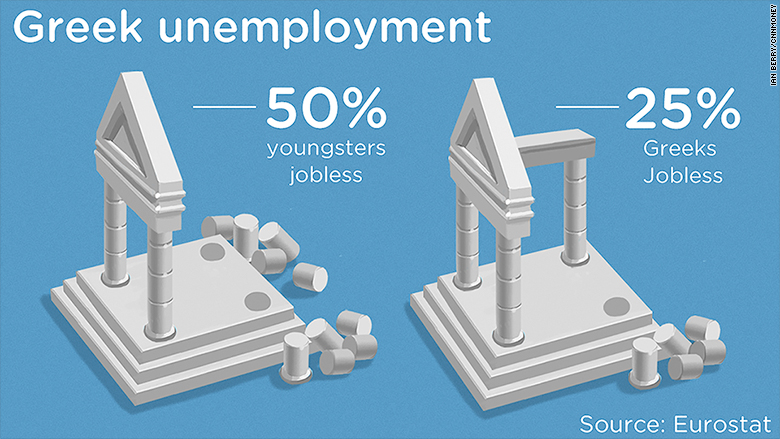

Unemployment stands at 25%, and almost double that for young people. If the impact of previous bailouts is anything to go by, unemployment is likely to rise further in the months to come.

Greece received its first bailout in 2010, when unemployment was about 15%. It shot up to 21% the following year. The second bailout was agreed in 2012, when unemployment stood at 26%. It rose to 28% in 2013.

3. An impossible goal?

Europe says the aim of the new three-year bailout, and its accompanying reforms, is to stabilize Greek finances while the country gets its house in order so that it can ultimately stand on its own feet again.

But the International Monetary Fund has already warned that the plan is unworkable, without a hefty dose of debt relief.

The IMF says Greece's debt has become "highly unsustainable" and forecasts it will peak at close to 200% of GDP in the next two years.

Right now, Greece's debt-to-GDP ratio is 172%. By contrast, the U.S. has a debt burden of about 88%, and Germany 53%.

"The IMF...makes clear that lending more money to a country that is already hopelessly in debt is never going to be a solution," Oxford Economics' Nixon said.

The risk is that Greece can't generate enough surplus cash from tax revenues or economic growth to service its debt. That could mean another crisis a few years down the road.