Puerto Rico will almost certainly be in default for the first time ever by Monday.

The commonwealth needs to make a $58 million debt payment by August 1, but top Puerto Rican government officials say that they don't have the money to pay.

"We believe the probability of a default is approaching 100%," says Ted Hampton, a senior analyst at Moody's who covers Puerto Rican bonds.

The August 1 payment is a very small part of the commonwealth's $70 billion in outstanding debt. That doesn't bode well for the rest of the debt.

Puerto Rican Governor Alejandro García Padilla claims the commonwealth can't pay all of its debts. He says the island's economy is in a "death spiral."

Related: Who owns Puerto Rican debt?

But will it be deja vu? Puerto Rico has been in this scenario before. There was a lot of speculation that the island would default on its July 1 debt payments, but it found enough money to make all of them.

This time may be different. The governor's chief of staff, Victor Suarez, said earlier this week that the island won't make all of its August 1 payments.

If Puerto Rico doesn't make this payment, it will short change its own people and credit unions, not Wall Street hedge funds. The $58 million is suppose to go to Puerto Rico's Public Finance Corporation -- where roughly 900,000 Puerto Ricans own a small slice of the debt via credit unions.

Puerto Rican officials are strategically choosing to default on this debt because there's a low risk that these creditors will have the legal willpower to sue the government, expert say. The commonwealth will probably make its other debt payments next week owed to creditors who have more legal power and could threaten to sue.

"The PFC debt: it's a small amount, it has very weak legal protection and it's owned by people who are unlikely, necessarily, to sue the government," says Cate Long, founder of Puerto Rico Clearinghouse, a research firm focused on Puerto Rican debt.

In the big picture, next week's payment (technically due by Monday, Aug. 3) is another chapter in Puerto Rico's economic tragedy.

Related: Why Puerto Rico's economy is in a 'death spiral'

Economy in collapse: The island's economy is in crisis mode after years of massive government spending, huge energy costs and mounting pension liabilities.

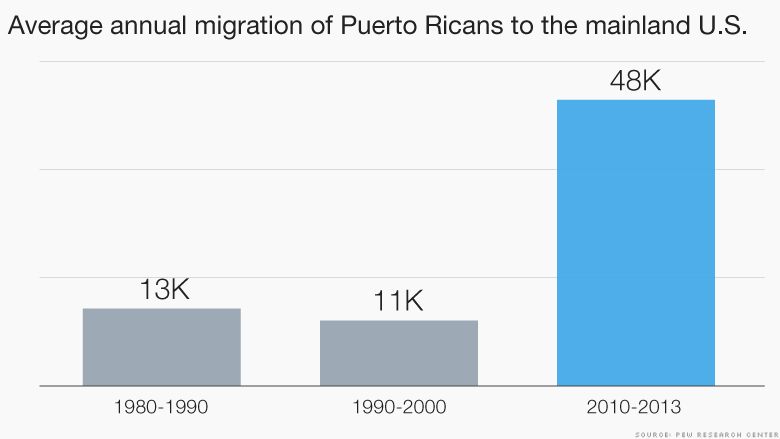

The population is shrinking by tens of thousands as Puerto Ricans flee to Florida and Texas in search of more stable work. The exodus is reaching levels last seen during the 1950s -- the "West Side Story" era, according to the Pew Research Center.

Puerto Rico's unemployment rate is 12.6%, more than twice the U.S. unemployment rate (5.3%), according to the Labor Department.

To help Puerto Rico elude some of its debt burden, Governor Alejandro Garcia Padilla has implored the U.S. Congress to give Puerto Rico something it badly needs: Chapter 9 bankruptcy rights.

Related: Puerto Rico's terrible economy is causing a population exodus

Chapter 9 for Puerto Rico looks unlikely: Puerto Rico wants the same thing all U.S. states have: Chapter 9 bankruptcy. It's a part of the bankruptcy code that gives states the right to allow towns, municipalities and local institutions in their state to declare bankruptcy. For example, Detroit was allowed to file for bankruptcy because Michigan has Chapter 9 rights.

Since it isn't technically a state, Puerto Rico was never given Chapter 9 bankruptcy rights. The island's government also can't appeal to an outside fund, like the International Monetary Fund, for help because it isn't a country. Puerto Rico's representative in Congress has gathered some support for a bill to give Puerto Rico chapter 9 bankruptcy rights, but it's unlikely to become law, experts say.

Even if Puerto Rico got Chapter 9 rights, much of Puerto Rico's current debt likely wouldn't be eligible for bankruptcy courts, according to a Moody's report. That's because the island itself couldn't declare bankruptcy, only municipalities within Puerto Rico.

Still, Puerto Rico needs a way out. The governor has put together a task force to come up with a work out plan by the end of the summer.

"They need some type of mechanism to restructure their debt," says Mark Heppenstall, portfolio manager at Penn Mutual Asset Management. Heppenstall would not comment on whether his firm owns Puerto Rican debt.