Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have a seemingly simple way to lower the high cost of drugs in the U.S.: Let Medicare flex its gigantic muscles and negotiate lower prices with drug manufacturers.

When Congress overhauled Medicare in 2003 to pay for prescription drugs, lawmakers banned the agency from negotiating with drug companies as a concession to the pharmaceutical industry. Instead, the insurers who cover the roughly 42 million enrollees in Medicare's Part D drug program obtain their own discounts.

But many experts argue that the federal government could do a better job than the insurers -- pointing to the deeper discounts obtained by Medicaid and the Veterans Health Administration, which can bargain directly.

Medicare pays 83% of a brand-name drug's official price, on average, according to a recent study by Carleton University and Public Citizen, an advocacy group. Medicaid pays 48% and the Veteran Health Administration 46%.

We're not talking chump change. Medicare shelled out nearly $70 billion on prescription drugs in 2013. Allowing the federal government -- instead of insurers -- to negotiate prices could lower Medicare's drug tab by up to $16 billion a year, the study's authors estimated.

"The more the fragmentation, the less rebates you can get," said Marc-Andre Gagnon, associate professor of public policy at Carleton University in Canada. "The U.S. and Canada have the most fragmented systems and the highest prices you'll find."

In many European and other advanced countries, where public healthcare is the norm, the governments often determine what drugs they will cover and at what price. Countries sometimes refuse to cover medications they believe are priced too high. Any private insurers in those countries then follow the government negotiated rate.

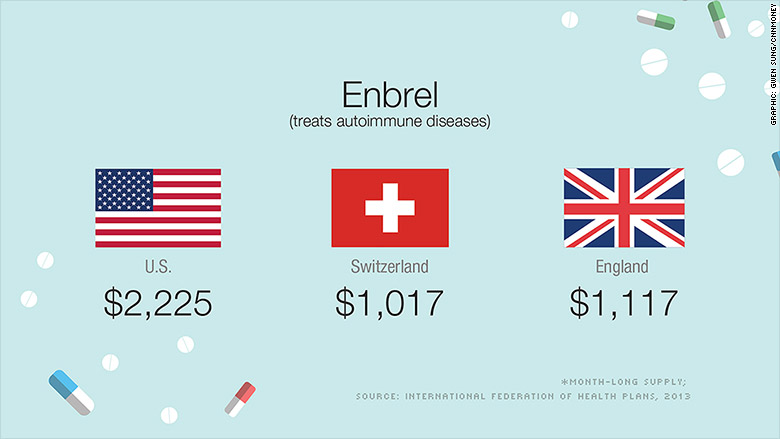

As a result, medications can be half the price across the pond. For instance, insurers' average negotiated price for a month's supply of Enbrel, which treats autoimmune diseases, was $2,225 in the U.S. but only $1,017 in Switzerland and $1,117 in England, according to a 2013 International Federation of Health Plans report. The price of the acid reflex medicine Nexium (now available in generic version) was $215 in the U.S., but only $23 in the Netherlands and $58 in Spain.

The high cost of drugs in the U.S. takes a toll on patients' wallets and health. Some 16% of diabetes patients in Medicare fail to fill at least one prescription a year because of the cost, according to the study. Americans in general have a much higher rate of skipping meds because of cost than other advanced countries.

The American pharmaceutical industry argues that giving the government bargaining power would upset the competitive nature of the Part D program. Insurers currently use the savings they negotiate to reduce premiums and deductibles.

Medicare stepping in would result in higher costs and fewer coverage options for enrollees, said the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, a trade group.

"The program is working incredibly well for seniors and for taxpayers," said Robert Zirkelbach, the group's spokesman, noting total Part D program costs are 45% -- or $349 billion -- lower than the Congressional Budget Office's initial 10-year projections.

The Democratic presidential candidates, however, have the backing of the vast majority of the Americans on both sides of the political aisle: Some 83% said they support allowing the government to negotiate with drug companies, according to an August poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation. This includes 93% of Democrats and 74% of Republicans.

However, the pharmaceutical group conducted its own poll this week, asking whether Americans would prefer to have insurers or the federal government negotiate prices. The response was two-to-one in favor of insurers, Zirkelbach said.