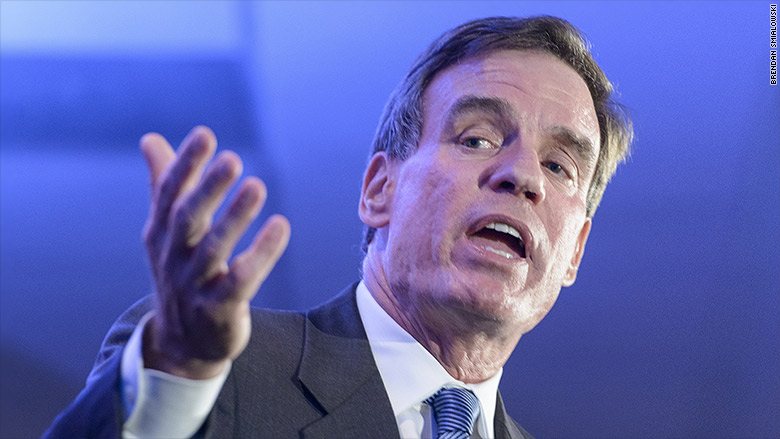

On-demand firms need a regulatory timeout -- a breather from legal battles while they figure out a new way to classify their workers, according to Virginia Senator Mark Warner.

Warner sang the praises of the on-demand workforce during a keynote presentation delivered via livestream at the TAP Conference on Thursday. But he also warned that policy has a lot of catching up to do.

Companies like Uber, Handy, and Alfred are giving Americans unprecedented flexibility, he said.

"People can suddenly monetize their time, their apartment, their car, their bike, their parking space, their personal services in ways that never before have taken place," said Warner, who added that he's been a venture capitalist and businessman for longer than he's been a politician. "This opens up a whole new series of opportunities."

But with new opportunities comes a need for new policies.

Many companies, like Uber, rely on contract workers to perform services. While it allows workers flexibility, there's a lot of downside. Independent workers aren't entitled to minimum wage, overtime compensation, unemployment insurance or protection from workplace discrimination. They also aren't entitled to benefits and don't have the right to join a union.

Other companies like Managed by Q and Alfred hire workers as part time W-2 employees. They say this allows them to offer flexibility, but there are still limitations.

Warner says there needs to be a third option.

"Quite honestly, what I found is that neither one of those two classifications are going to work in the 21st century," he said. "We have to think more creatively."

However, current regulatory constraints are deterring companies from testing out what those might look like. And Warner emphasized that experimentation was vital, since "we don't know what would really work."

But he did have a couple ideas of where to start. He discussed a model similar to the healthcare exchange where people could shop an electronic marketplace with various benefit programs, or possibly a benefit pool that let workers bank contributions from various employers.

Mostly importantly, Warner said there will needs to be a short-term regulatory timeout so firms can experiment without the fear of being sued.

"It may not be New York or California -- but certain states who are willing to give a little bit of regulatory forbearance to allow some of these enterprises to actually try social insurance models," he said. "If we're going to get it right, we have to be more nimble with this."

After all, on-demand workers are a sizable piece of the U.S. workforce -- and it's not just millennials. Baby Boomers and even senior citizens are taking advantage of the flexibility and supplemental income that this type of work offers.

"No longer do you ask somebody where do you work, it's, 'What are you working on?'" he said. "What I hope I can be is your partner in getting [a new social policy] right."