Wall Street's hedge funds can't wait for Argentina's next president.

They've been battling with the current president, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, and her predecessor and late husband, Nestor, for 12 years over huge debt payments. That could soon change.

Argentines will elect a new president on Sunday, and a major issue is whether the new leader will finally end the country's fight against New York hedge funds.

After defaulting on $95 billion of debt in 2001, the country has been in a decade-long fight in courts with the hedge funds, also known as "vultures" in Argentina, South America's second-largest economy.

The unresolved debt debacle has shut out Argentina from much of the global economy while it has suffered from massive inflation, declining cash reserves and meager economic growth.

There are three candidates running for president: Daniel Scioli, Mauricio Macri and Sergio Massa. Scioli is most similar to the current president and he's leading in the polls.

But many experts say Macri, second in the polls, is Wall Street's favorite and most likely to negotiate with the hedge funds. That's because Macri has proposed economic and financial reforms that would undo Kirchner's policies, which investors strongly dislike.

"Argentina's debt problem has to be fixed quickly so that we can return to having credit," Rogelio Frigerio, the leader of Macri's political party, PRO, recently told CNN's Diego Laje in Buenos Aires. "We need to finance these [economic] development policies."

Related: No deal: Argentina in default as talks fail

Argentina's record-breaking default and the 'vultures'

The hedge funds, led by billionaire Paul Singer, want about $1.5 billion from Argentina.

Argentina broke the record books when it defaulted on $95 billion of debt.

Singer's fund, NML Capital, and others scooped up the nearly-worthless debt soon after the default, then waited while the debt gained value and now they want full repayment.

Over the years, the Kirchners renegotiated terms with 92% of its creditors so that they would accept a huge discount, or "haircut," on debt payments.

These hedge funds are called vultures for picking up cheap, worthless debt of developing countries, then suing them afterward for much more money.

Argentina has offered to pay creditors 30% of the face value of the debt. Singer doesn't want that, even though his fund already stands to profit from the rising value of the debt.

Singer wants full repayment. And a New York judge, Thomas Griesa, agrees with him.

In fact, Argentina tried to pay the creditors that agreed to the lower amount, but Griesa blocked the payment last year. The judge said that Argentina has to pay the holdouts and other creditors at the same time. Negotiations between Argentina and NML last year failed to reach an agreement.

Until Argentina settles with the holdouts, its economy essentially can't grow much because it can't get access to foreign investment.

Another problem is that Argentina, under Kirchner, has manipulated its currency, started massive spending programs and lost the trust of many independent economists inside and outside the country.

Related: America's 'smart money' getting burned in Brazil

Peso problems

For years, ordinary Argentines couldn't buy dollars from local banks because of government restrictions. Now they can, but there's still major limits on how much they can exchange.

So many Argentines exchange pesos for dollars on the black market because they don't want to deal with government restrictions.

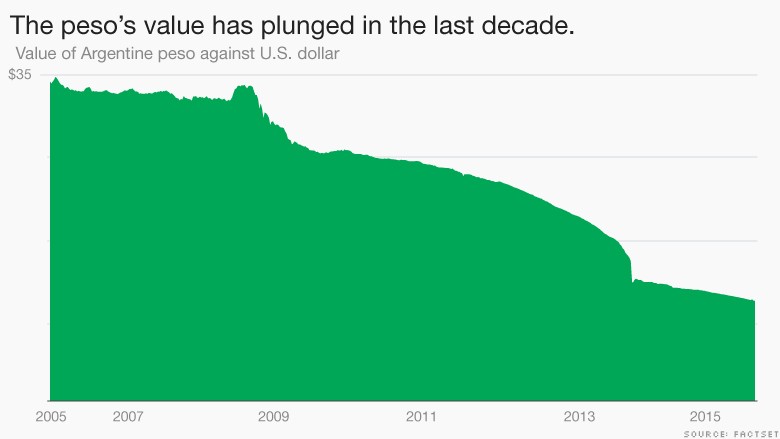

Three years ago, one dollar equaled about 6 pesos on the black market. Now one dollar gets you 16 pesos. The official exchange rate is 9.50 pesos to the dollar.

"We think the Argentine currency is significantly overvalued," Sebastian Rondeau, a Bank of America economist, wrote in a research note. He says the real value is closer to the black market exchange rate.

Related: Colombia could profit from its peace deal to end civil war

Change of tune: we could negotiate

For years, presidential candidates have said they would never negotiate with the hedge funds. But each of the current candidates, or their advisers, have hinted that they would consider negotiating with the holdouts.

But settling with funds would be a deeply unpopular decision. In a politically-divided nation, Argentines unite over their hatred of the hedge funds.

"The problem is -- how do you package it, how do you sell it after saying you would never negotiate with them," says Eugenio Aleman, an Argentine and senior economist at Wells Fargo (WFC). "They have to figure out how to pay."

Investors can't wait for a new president. Argentina's stock index, Merval, is up 27% so far this year, and experts say it's because of optimism that the next president will resolve the dispute and open up Argentina's economy to foreign investment.

NML Capital declined to comment for this article, but it has repeatedly offered to negotiate with Kirchner.

"Argentina is going to pay. The question is how much it's going to pay," Daniel Artana, senior economist at the Foundation for Latin American Economic Investigations, told CNN in a phone interview from Buenos Aires.