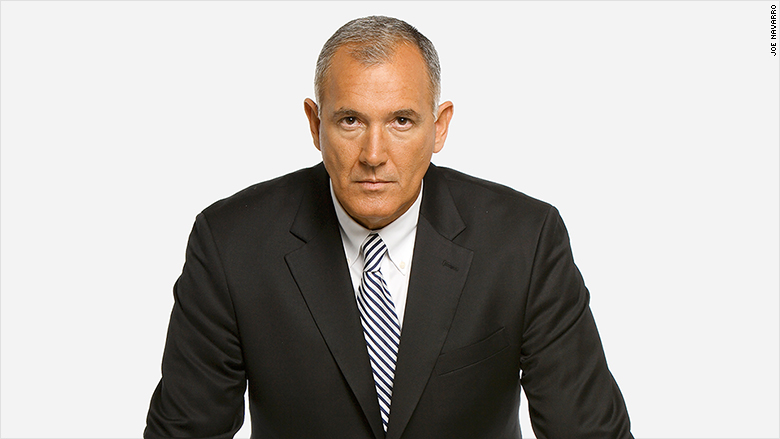

They say "you should never let them see you sweat." That goes double if you're face to face with Joe Navarro, who became an expert at reading body language while working for the FBI.

After 25 years of hunting spies, Navarro is now writing books (11 of them so far) -- and working on a film project with George Clooney based on his yet-to-be published novel "Three Minutes to Doomsday." The book, which Navarro and writer Howard Means are currently writing deals with Navarro's role in tracking down Clyde Lee Conrad, an Army officer who sold secrets to Hungary during the Cold War.

But it's Navarro's own story that may be the most intriguing.

Born in Cuba, Navarro witnessed the Bay of Pigs invasion. While escaping Cuba's repressive regime at the age of 9, he was separated from his family for months. Eventually, he was able to get on an airplane to Miami and reunite with his parents just before the Castro regime banned travel for Cubans heading for the United States.

Years later, as a teenager in Miami, he was stabbed and nearly died trying to stop a robbery at the department store where he worked. The event would change his life, and eventually lead him toward his career as an FBI agent, where he learned how to fly planes, storm buildings and track down international spies.

Here is Navarro's American Success Story:

What was life like growing up?

Like the Syrian refugees fleeing to Europe, or the kids coming here from Latin America, I came to the U.S. in the 1960's as a nine-year-old refugee from Cuba.

I came when the Miami school system was overwhelmed by Spanish speaking kids. I remember the hysterical fear that spread in Miami when we arrived.

My parents understood the value of an education but they worked two or three shifts a day as waiters. They had little time to work with me on my studies but they encouraged me to learn and explore and to check out books from the library.

I started working when I was 11. I did odd jobs in the neighborhood from dog sitting to cleaning. I worked as pool boy handing out towels at the Deauville and Carillon Hotels and at night at a nearby putt putt golf course, keeping the place clean. Back then no one asked how old you were.

The first thing I bought myself was a watch so I could always be on time.

In my final year of high school, I was looking forward to playing football in college. I had 18 offers to play from as far away as New York to Georgia.

One day, there was a robbery at the department store where I worked. The manager yells over to me to stop two guys who had just robbed us. But he didn't tell me they had weapons!

I was stabbed. Before help arrived, I was bleeding out. I almost lost my life. The robber cut the artery under my arm. I had to get 180 stitches and was in the hospital for 21 days.

Because of my injury I ended up losing all my football scholarships but one: Brigham Young University. BYU had a scout in Miami who had come to see me play. He came to the hospital and told me that coach LaVell Edwards would like for me to try out once I healed.

I tried out, but I simply was not ready. I was not going to be an athlete. But because my family was poor, BYU worked with me. I studied criminology instead.

There were FBI and CIA scouts on campus. One day, two FBI agents knocked on my door and said, "we want you to fill this application." I was 23 at the time, so I applied.

How did your family fit into your neighborhood?

It was very tough because we had to move around a lot. We were constantly moving to another rental because it was cheaper or closer to work for my dad. By the time I was 18, we had moved nine times.

In Cuba, my dad was a bookkeeper at the local electric company and my mother worked there as a secretary. These were good paying jobs -- good enough to vacation in Miami every once in awhile.

But when he came to the U.S., the only jobs my dad could find were menial labor. He did construction, picked citrus, cleaned floors, drove a truck and worked as a busboy and later as a waiter. But he never complained. He did what he had to do. I learned a lot from him.

For the first ten years in this country he never took a day off. He would often walk to work rather than ride the bus.

My parents really wanted to fit in. They wanted to contribute to their new country, but there were people who saw us as a threat.

I had a strong accent. I remember how we were made fun of because of the way that we pronounced certain words. I thought, "I have to lose my accent."

In a way, that triggered my interest in body language. You could really tell what someone was saying, not only by what they said but by how they said it and what they were doing when they said it.

I could tell, for example, when people were being polite with their face but not being polite with their feet. If you're engaging someone in a conversation, glance at their feet. If they want to get into a conversation they'll turn their feet towards yours, otherwise they won't. That's "the inclusiveness factor."

It helped me to understand if people were genuine.

What's the biggest hurdle you've had to overcome

The first one: I was in Cienfuegos, Cuba, on the day of the Bay of Pigs invasion. I can still remember the gunfire and how everything went dark in town. I remember fearing the "Barbudos." Those were the "Fidelistas." They did awful things.

Then there was my family's separation. The government of Cuba intentionally split us up. My mother had to leave first with my younger sister. She had to choose between leaving to save herself and her [youngest] daughter without knowing if she'd ever see the rest of her family again, or staying in Cuba and maybe being killed. Even if she stayed, she could have been separated from the rest of her family forever.

I really didn't understand what was going on. All I knew was that the bearded men in their filthy green uniforms with guns ruled. They made life miserable for all of us. They would stop people thought to be opposed to the revolution, stand them up against the wall and shoot them dead.

My father left through the Venezuelan embassy. He jumped the fence and requested political asylum. He left Cuba under the protection of the ambassador.

My older sister and I stayed with distant relatives until we were allowed to leave.

We left just before Cuba closed its doors. We were all reunited in Miami, but it was so stressful and we had no money. Everything had been taken from us.

I have not been back to Cuba. Our house in Cienfuegos still stands. It's occupied by the government that took it over in 1962. I would love to go back, but I think it is too early yet.

The embargo was a complete waste of time. I think Fidel could have been marginalized if there had been trade with Cuba and the infusion of millions of tourists. I have always been against the embargo even though my father who lost so much was for it.

Although there have been these challenges, I've always been looking ahead, asking myself, "What do I do now? How do I make this experience better?"

What was your big break?

My first big break was being accepted to study at Brigham Young University in Utah. My other big break was being hired by the FBI. Someone at the agency saw me and said, "this guy looks like he would make a good FBI agent." I know of no other FBI agent who was recruited.

I did a lot of things for the FBI. I got to fly airplanes, I got to be in the SWAT program and in the behavioral program.

Do you feel that you've had to work harder than your peers to get ahead?

I knew things were more difficult because I was living in a country with different social norms and a different language.

I was playing catch-up on so many things; learning about the founding fathers of America, American history, all those things we learn early on.

I always felt I had to prove myself, if not academically, then as an athlete. Certainly I had to disprove stereotypes about Latinos.

Even in the FBI I had to demonstrate, that I belonged there. I strived for excellence. In the back of my mind I told myself, "I have to prove myself worthy, I have to make my parents proud -- always, but also I need to thank this country on behalf of my family for allowing us as refugees to be exiled here."

When I hear the rhetoric nowadays against refugees, I cringe and wonder how much less welcomed I would be today.

What's the riskiest thing you've ever done to get ahead, and would you do it again?

You would think the riskiest thing I have ever done was work for the FBI.

But when I retired from the FBI after 25 years, I decided to go on my own and not work for anyone else again. That was the toughest decision and the best.

I didn't know what awaited me. That decision alone changed my life. Relying on my own skills was gratifying but also frightening. What if I fail? What if there is no work?

People began to hire me to talk. This led me to more and more speeches and conferences to the point where I do about 45 a year.

That led me to writing books, one which became an international bestseller in 29 languages, "What Every BODY is Saying" and later another bestseller, "Louder Than Words." That one accompanies my yearly lectures at the Harvard Business School.

I would not have achieved those things if I had not taken a chance.

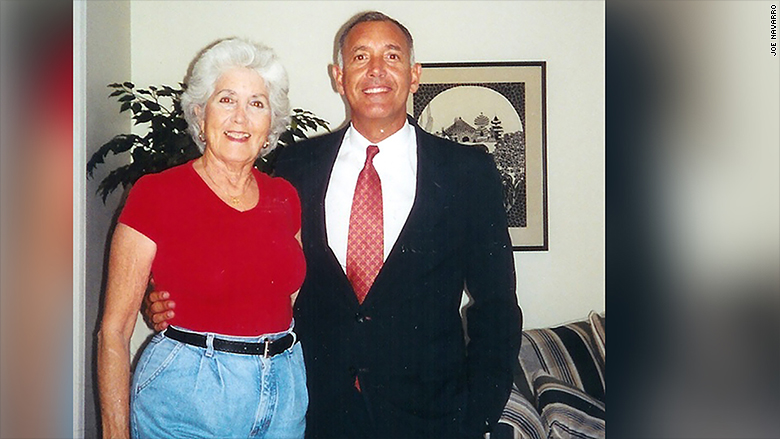

Who's the one person who got you to where you are today?

I would have to say it's my mother because she set the example of no matter what you're handed, you have to make the best of it.

She went from having a very good life in Cuba, to cleaning tables and working in a butcher shop. She taught me stewardship. She never complained and she made it better. That's the best example of everything.

Some would say it's a coach or teacher but she was the best example of everything. Don't complain, contribute.

What's the one thing you do every day that helps you to achieve your goals?

I write every day. I'm very disciplined.

I'm writing what, in essence, will be my twelfth book.

What is your quirkiest habit?

Reading people's body language. My wife will tell you that every now and then she has to tell me to "knock it off."

She'll be compressing her lips or touching her neck and I'll ask if she's OK. And she'll say, "Knock it off! No. I'm not having a good day, but there's nothing you can do and it's not your fault."

People ask me 'Do you ever turn it off [reading body language]?' And no, I never do.

It's something of a curse. I can see when children don't get along with a parent. Or when someone is about to break up.

I was on a cruise one time, and one of the professors who was on it with us said, 'we should do this again next year!'

When he said that I noticed his wife grabbed her necklace and made a fist in her throat area. We humans protect our throat area in times of stress or when we feel threatened. I immediately knew that there was something wrong. Something had just happened that made her feel uncomfortable. About six weeks later she filed for divorce.

Nina Vaca: Daughter of immigrants now runs a $650 million firm

Daymond John on hip-hop, his mom and making it big

From food stamps to leveraging a $24 billion powerhouse for good