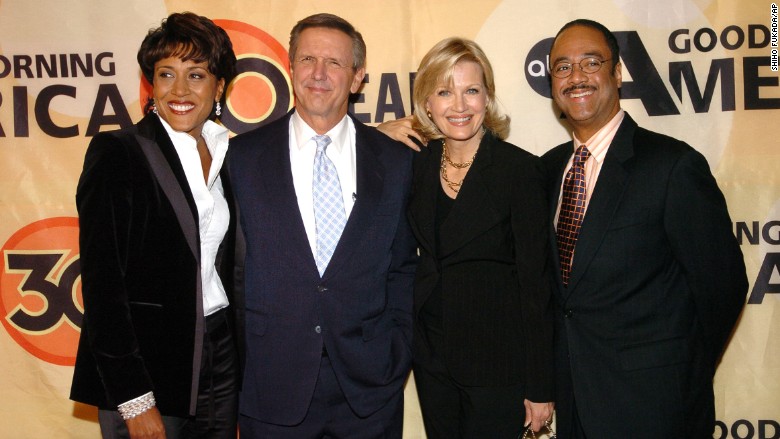

ABC's "Good Morning America" celebrated its 40th anniversary Thursday by bringing back virtually all of its past hosts and contributors -- David Hartman, Joan Lunden, Diane Sawyer, Charlie Gibson and many more. To mark the occasion, I dug up a draft of my 2013 book "Top of The Morning," recounting how the show was created in 1975. This "lost chapter" didn't make the final cut for the book, but it demonstrates some of the vital lessons of morning TV.

ABC's "Good Morning America" was born in 1975 -- as so many television shows are -- out of desperation.

NBC had invented morning TV with the "Today" show two decades earlier. It had no true competition. The morning news on CBS was forgettable at best, unwatchable at worst. And ABC had nothing.

In fact, some ABC-affiliated stations were talking about switching to NBC or CBS if the network could not provide a credible 7 a.m. show to start the broadcast day. This was a crisis for ABC. At least that's what Bob Shanks, a network vice president, told David Hartman, the man who would soon solve ABC's problem.

There was tremendous pressure "to get on the air ASAP," Hartman recalled, because some affiliates "had threatened to jump ship."

'GMA' born of the ruins of 'A.M. America'

When a new president of ABC, Fred Silverman, took over the network in the summer of 1975, he put Shanks and another ABC vice president, Ed Vane, in charge of coming up with a true challenger to "Today." The two men combed through lists of names of possible hosts -- 150 or 200 by Vane's recollection. One name was David Hartman.

Shanks called Hartman in early October and asked if he'd be interested in hosting the new morning program that ABC was making. Hartman said yes. Just thirty days later, on November 3, "Good Morning America" debuted, and it's been on the air ever since, dueling with "Today" for first place in the notorious TV morning show war.

ABC had tried a morning show earlier in the year, to disastrous effect, which had heightened the pressure on Silverman to produce a new show worth watching.

The disaster, titled "A.M. America," premiered on January 6, with co-hosts Bill Beutel and Stephanie Edwards and news reader Peter Jennings. "It was the guinea pig on which everything that could go wrong, did," Edwards told an interviewer a decade later. The media overhyped "A.M. America" as ABC's attempt to dethrone "Today" show co-host Barbara Walters.

But the show itself was under-developed. "Thirty seconds before we hit the air, they told me my outfit -- a gray suit -- was too bland and could kill the first day's show," Edwards recalled. (The producer wanted red or orange or green.) "What a confidence booster! I should have known then what I'd gotten myself into."

Four months and three days later, ABC announced that Edwards was off the show. She was allowed out of her contract, she said, under the condition that she not talk about how bad the experience had been. Beutel and Jennings headed for the exits soon thereafter.

What went wrong? "We were doing the 'Today' show, but without the 25-year head start," ABC producer George Merlis said.

So from the ruins of "A.M. America" came "GMA." Instead of an imitation of "Today," it would be a more entertaining, more appealing alternative.

Enter David Hartman: The actor turned host

Hartman himself was an alternative: He was a famous actor, not a reporter like the co-host of "Today" at the time, Jim Hartz. Hartman played a ranch hand on the Western series "The Virginian," then a doctor on "The Bold Ones: The New Doctors" and an English teacher on "Lucas Tanner," all on NBC.

In the early 1970s, an executive at NBC "asked if I'd be interested in switching over to working at NBC News," Hartman said in an interview. "There were logistical challenges we could not solve, but the seeds were being sown." Hartman subsequently created a production company and made a documentary that showed the birth of a child for the first time on American television.

NBC also lined Hartman up to co-host one day of the "Today" show. As part of its celebration of the United States Bicentennial, "Today" was going to take itself to a different state every Friday in 1976, and Hartman was going to co-host from his native Rhode Island. And then came Shanks' phone call. Hartman had to cancel on "Today" -- because he'd be hosting "GMA."

"I thought it an extremely bizarre choice," Merlis said. Given Hartman's acting background, "the journalists among us were anguished."

"The first week looked like it would prove us right," Merlis continued. "And then David, who was the single hardest-working man in the history of television, began to prove himself. He would ask questions that caused the news guys to groan and wince. But he was asking the questions the viewers would have asked, not the questions TV newsmen ask to show off how much they know." This was Hartman's instinct.

And after "it started working for the show," the news guys "began to ask those questions, too," Merlis added.

But we're getting ahead of ourselves here. Let's go back to the very beginning. The first episode of "GMA" was rushed onto the air with only a few weeks notice, which meant recruiting staff, leasing a studio and designing a set with unusual haste. Rehearsals with Hartman did not start until just a few days before the Monday premiere date, much later than they should have. In fact, after seeing the first rehearsal, Silverman feared that the staff wasn't ready to do it live and insisted that the premiere be taped -- so they all came in on Sunday morning and taped it from 7 to 9 a.m. as if it were live. The producers left holes for the live newscasts by ABC News.

"Looking back," Merlis said, "I'm not sure how we did it."

The tape was broadcast the next day by only half of ABC's affiliates. There were, according to Hartman, no paid commercials, just "make goods," an industry term for free commercial time given to advertisers to make up for an earlier ratings shortfall. ABC clearly still had some convincing to do.

But "research determined that younger viewers and women weren't watching 'Today.' So we sought to build an audience in that demographic," Merlis explained. That meant fewer interviews with politicians and more conversations about child-rearing. (Although the producers had to fight ABC's standards and practices department from time to time: The first time "GMA" tried a segment on breast feeding, the censors didn't want the word "breast" said aloud. "They relented when I suggested a whole range of saltier substitutes," Merlis said.)

When the show debuted, Hartman had to teach himself to look directly into the television cameras, reversing years of actor training that had taught him to do the opposite. But there were advantages to having an actor as host: Hartman had lots of friends in Hollywood, and he wrangled many of them onto the show. And, randomly enough, "Lucas Tanner" became a big hit on Israeli television, giving Hartman great access to Israeli political leaders.

Hartman's first on-air partner was Nancy Dussault, a musical theater star who was sorely miscast and was fired in a matter of months. She was replaced by Sandy Hill, an anchor at KABC in Los Angeles. Silverman told staffers that Hill had been his first choice, anyway. But "Sandy started off with a couple of strikes against her," Merlis recalled. "The staff loved, loved, loved Nancy, so they were indisposed to like her replacement." (A similar attitude among the staff would hurt Deborah Norville at the "Today" show more than a decade later.) They eventually came around; by the end of the decade, Time magazine said she was "much admired by the GMA staff." But, the magazine reported, there was another problem: Hill "got along with Hartman so poorly that she hardly talked to him on camera."

The folksy, charming Hartman, not Hill, was the obvious star -- and pointedly the only person called the "host" of the show.

Within a few years "GMA" was on the "Today" show's heels; audience research commissioned by NBC in 1978 showed that Hartman was more relatable and approachable than the "Today" show co-host who replaced Hartz, Tom Brokaw. "The audience rated the two shows equally in terms of content and style, but was in love with David Hartman," said Steve Friedman, who was in charge of "Today" back then. "He was 'everyman,' and he was the difference."

NBC officials were flustered. By then Silverman, who'd been the president of ABC, had become the president of NBC. He chaired a meeting to discuss the audience research -- and more importantly what to do about it. Friedman, a friend of Brokaw's, mused that perhaps the money spent on all the research should have been spent to hire a hit man to kill Hartman instead. Silverman... didn't laugh. The room fell silent for a moment.

'GMA' was entertainment, 'Today' was news

There was another important difference between "GMA" and "Today."

"GMA" was a product of ABC's entertainment division, not ABC News. It was, as TV critics were quick to point out, "softer" than the "Today" show. While Hartman might dispute the s-word, he said it "had a different look and feel from a traditional news program," including a more conversational style (the writers would substitute "a lot" for the more formal "many," for instance) and a set that was supposed to look like a suburban home (with a living room, a kitchen, etcetera).

ABC News produced the newscasts that were shown within "GMA" every half hour. And the anchor of the newscasts, Steve Bell, joined Hartman for most of the show's hard news interviews in the first few years, blunting some of the critics' complaints from about turning an actor into a morning show host.

Hartman felt that because "GMA" was not produced by the news division, "it was incumbent on us to prove that we could present a fine news and information program." And as the show progressed, he felt satisfied that it did. In 1976, when Jimmy Carter was elected president and gathered his entire cabinet for a retreat in Sea Island, Georgia, "GMA" went along for a two-hour live show, completely breaking the show's usual format. "That one day put 'GMA' on the map as a serious contender," said Merlis, who recalled that Ferber's replacement as executive producer, Woody Fraser, had "knock-down, drag-out fights" with his network bosses to make it happen.

The Carter interview was led by Bell, the news anchor, not Hartman. But in 1980, when Ronald Reagan (a fellow actor) was elected president, it was Hartman who scored the post-election interview. "ABC News was furious and wanted to have a representative there -- but David was brilliant, really," said Susan Winston, who produced the interview. "He brought humanity to his interviews. He was the best prepared anchor ever."

The "Today" show's standing ties to authors, actors and Broadway stars "made 'GMA' far more enterprising in finding stories and guests," Merlis recalled. The upstart was especially hungry for "real people." Rather than having a reporter stand in front of a coal mine for a story about a strike, the theory went, why not talk directly to a striking miner and his family? This strategy continued into the 1980s; as Winston put it, "'Today' was busy booking the head of the auto union and I was booking the out-of work auto workers."

The strategy reminded Merlis of a class lecture from his days at Columbia University. The professor, the New York Times photographer Bill Eckenberg, showed the class a picture of Babe Ruth on the day in 1948 that the Yankee player's No. 3 was retired. Most of the photographers on the field of Yankee Stadium that day stood in front of Ruth and used flashbulbs -- the easy way to get the shot. But one photographer, Nat Fein, stood behind the Bambino and used the available light. Fein won the Pulitzer Prize for his now-iconic photo, "The Babe Bows Out." Eckenberg's lesson to the class was this: "Walk around the job before you take a picture."

Applied to morning television: think unconventionally. Out-think the opponent, in this case the "Today" show.

"ABC decided that 'Today' was very New York-centric," said Phyllis McGrady, who arrived at "GMA" in 1977 and went on to be a senior vice president at ABC News. "So ABC created what I would consider a much more populist, relatable morning program. They thought, 'Let's make it more about America' -- thus the name 'Good Morning America.' "

After 4 years, 'GMA' catches up with 'Today'

By the end of the decade, four years after "GMA" had launched, the two morning shows were effectively tied -- a position that neither show particularly liked. "GMA" had the momentum, but "Today" was still No. 1.

Brokaw vented in a November 1979 conversation with The Associated Press: "I've been reading for two years now that ABC and 'Good Morning America are on the move, but damn it, we're still winning. Maybe they will get us at some point. But we're still winning."

Motivational words for the staff of "GMA," perhaps. By January 1980 "GMA" started to beat "Today" some mornings. In February ABC placed No. 1 for three weeks in a row. In March reporters used words like "surrender" to describe NBC's response. Decades of monopolistic dominance by NBC, dating back to the dawn of television, were no more. The morning show war was on.

---

And the war continues to this day. "GMA" has been No. 1 in the ratings for the past three years, but in the past few months "Today" has retaken the lead in the key advertiser demographic of 25- to 54-year-olds. "Today" is on the verge of winning among total viewers, as well. Both shows have lost ground this year as morning viewers seek out other options for news and entertainment, both on TV and on smart phones. But "Today" and "GMA" remain profit centers for their respective networks. It was visible again Thursday as "GMA" spared no expense to commemorate its first 40 years. The studio halls were packed to capacity with former hosts, producers and friends of the show -- even Kathie Lee Gifford, who's now on "Today." Hartman, the very first host, had a grandfatherly air. Amidst all the fun, he made a serious point: "Doing this work is a gigantic privilege."