For Debra Henderson, love has come with a hefty price tag.

Her ex-husband was incarcerated multiple times, her boyfriend was recently released after serving seven months for a felony and her son has had a few brushes with the law. In all, Henderson, who is 40 and makes $60,000 a year working at an insurance company, has spent more than $32,000 on everything from bail bonds to lawyers to phone calls trying to maintain relationships with the men in her life.

Henderson is one of thousands of women who are shouldering the financial burden of incarceration of a loved one, particularly in black communities.

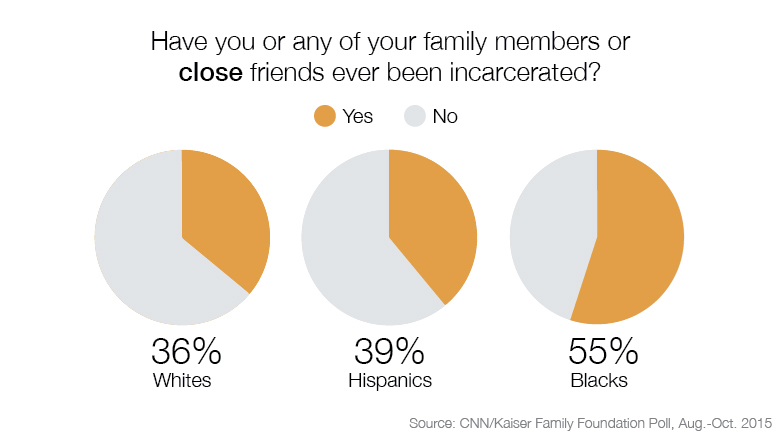

According to data from a CNN/Kaiser Family Foundation poll on race in America, 55% of black Americans said they either had been incarcerated themselves or had a close friend or family member who had been incarcerated compared to 36% of whites and 39% of Hispanics. Among these black Americans, nearly two-thirds said they earned less than $50,000 a year and only 21% said they had earned a college degree.

The financial costs of incarceration are steep. Inmates can be assessed fees for their daily stay in jail, probation and phone calls. In some cases, inmates accrued thousands of dollars in prison-related debt. Once released, many former inmates find that employers are reluctant to hire people with criminal records. As a result, it's often female relatives who are left footing a large percentage of the bills.

"Women of color are carrying the burden," said Gale Muhammad, the founder and president of the prison advocacy group Women Who Never Give Up. "It's all on us, the mothers, the wives, the sisters, the girlfriends."

Indeed, research on the financial costs of incarceration by the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights in 2014 showed that 83% of family members responsible for court-related costs were women. Families surveyed in the report also said they had trouble meeting basic needs like food, housing, utilities and transportation after a loved one was incarcerated.

The economic costs of loving someone in prison "has broken the black family," Muhammad said. "You've got women working two or three jobs to keep it together."

Henderson's troubles began with her ex-husband, who she met when she was 16. During their 15-year relationship they had three children and he was in and out of prison. Once she gave him $5,000 to help pay for a lawyer. Then she helped pay for phone calls and sent him money for his commissary account and visited him in jail, spending money on gas, tolls and vending machine food. In 2007, she had just refinanced the house they lived in when her husband was arrested again. The $10,000 she received from the refinancing went to a bail bondsman instead. "That money was supposed to be used to fix my home," Henderson said.

It was the last straw and the couple separated shortly thereafter. She never received child support from her ex-husband, who is currently incarcerated, and now that two of her children are above the age of 18 and the youngest is 14, she doesn't expect she will.

In March 2012, Henderson declared bankruptcy.

But Henderson's financial woes didn't stop there. In August 2014, Henderson's current boyfriend landed in jail. Henderson said she spent $2,450 on phone calls with her boyfriend during his seven-month stint. In October, the Federal Communications Commission ruled to cap the cost of phone calls made between prisoners and their families, which had become prohibitively expensive. But for Henderson, the ruling came too late.

Henderson said she also paid fees ranging from $3.95 to $10.95 per transaction for putting money into his commissary account. After her boyfriend was released, he was placed on an intensive probation program that cost a total of $3,000. She helped him pay for half of it. Of the $4,000 in monthly expenses the family incurs, including a mortgage of $1,850, food, gas and utilities, Henderson pays $3,000 a month. Her boyfriend contributes about $1,000, earning money from odd jobs like landscaping and working at a gym.

"Where I'm standing at 40 years old, I should have better credit from helping everybody else that's taken from me," she said.

And now Henderson's son has had a few brushes with the law and the costs of bail and lawyers' fees are already hovering around $6,000.

Experiences like the one Henderson has had "reveal how profoundly gendered the whole incarceration story is," said Bruce Western, a sociology professor at Harvard University who focuses on criminal justice. Male relatives "come to rely on these small points of social and financial stability occupied by these women who have steady jobs" or Social Security and disability benefits or housing vouchers, Western said.

The incarceration of men also reduces the family income by about 20% to 30%, Western said.

Race is also a critical part of the equation, he said. Since the majority of the prison population are men of color, "the women in those families are doing most of the caring work for their loved ones who are incarcerated or recently released from prison or jail," Western said.

Just ask Belinda, whose two brothers were incarcerated 28 years ago. "We had to dig deep, get clothes for school, make sure Christmas was happy," Belinda, who asked that her last name not be used, said. "The whole family pulled together to make ends meet."

Her mother took on various minimum wage jobs, including working as a hotel maid and frying chicken at a fast food restaurant. The financial stress of having two sons in prison ultimately took a physical toll on Belinda's mother, who ended up struggling with cancer, hypertension and blindness in one of her eyes.

Often the emotional and financial challenges continue once the man is released from prison, said Muhammad.

"We're the ones with the credit, we're the ones with the job, we're the ones putting everything in our name," said Muhammad, whose husband died in prison halfway through a 24-year sentence. "They need a ride, they need a suit, they have to go job hunting? You're putting them up. You're their sponsor."

After her husband died, Muhammad met another inmate while doing advocacy work for prisoners. They fell for each other, but the relationship didn't last. Now, both widowed and in their fifties, the couple has reunited. But Muhammad said she still notices the financial strain. While her boyfriend has also become a prison advocate and has a job as a barber, Muhammad makes more money than he does. So occasionally she pays for dinner and makes other contributions to their relationship.

His contribution? "He cooks dinner for me, I get my feet rubbed and I get the companionship of a guy that I care about that I couldn't be with for nine years."

The CNN/Kaiser Family Foundation poll was conducted August 25 through October 3, 2015, among a random national sample of 1,951 adults, including 501 Black and 500 Hispanic respondents. Results for all groups have been adjusted to reflect their actual national distribution. Interviews were conducted on conventional telephones and cellphones, in English and Spanish, by SSRS of Media, Pennsylvania. This poll was jointly developed and analyzed by CNN and staff at the Kaiser Family Foundation. Results for the full sample have a margin of sampling error of plus or minus 3 percentage points; for results based on African Americans or Hispanics it is plus or minus 6 percentage points. Read more about the poll.

More Race & Reality in America

The black-white economic divide in 5 charts

Who will you blame once Obama is gone?