China dumped billions of America's debt in December.

The largest owner of U.S. debt, China sold $18 billion of U.S. Treasury debt in December.

And it's not alone. Japan sold even more: $22 billion. In the past year, Mexico, Turkey and Belgium have also lowered their holdings of U.S. debt, all of which have led to a record annual dump by central banks.

Many countries are suffering from the global economic slowdown, forcing central banks to pull out all the stops to help buttress their economies.

Central banks in Japan and Sweden have resorted to negative interest rates to spur banks to lend more; the European Central Bank is buying bonds issued by its member countries; the People's Bank of China is injecting cash into its financial system.

For many central banks, selling U.S. Treasuries gives them the cash to prop up their collapsing currencies.

"These interventions are trying to add some air to the parachute," says Win Thin, head of emerging market currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman.

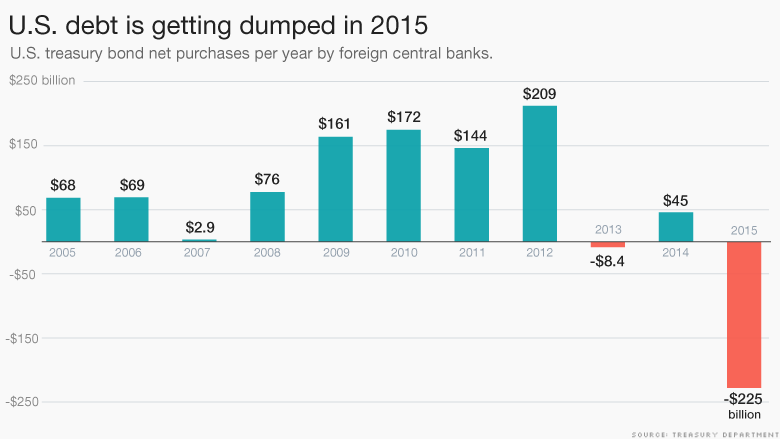

In total, central banks sold off a net $225 billion in U.S. Treasury debt last year, the most since at least 1978, the last year of available data. In 2014, there was a net increase of $45 billion, according to CNNMoney's analysis of Treasury data published Tuesday.

Foreign governments sold more U.S. Treasuries than they bought in 11 out of 12 months last year, according to Treasury data.

The U.S. debt dump is a sign of two things:

1. How aggressive central banks are acting to keep their economy afloat amid global weakness.

2. After years of building up savings -- the so-called "global savings glut" -- countries are starting to sell off their reserves.

Related: Global currency collapse: winners and losers

Currency collapse: central banks to the rescue?

A weak currency often reflects a slowing or shrinking economy. For instance, Russia and Brazil are both in recession and their currencies have collapsed in value.

Both these countries along with many developing countries depend on commodities like oil, metals and food, to power their growth. Commodity prices -- especially oil prices -- tanked last year and have continued to do so in 2016.

When commodities plunge, currencies tend to follow suit. And when currencies rapidly decline, cash tends to flow out of a country and into safer havens. So central banks have tried to prevent massive capital outflows by easing their currency collapse.

China spent $500 billion last year just to prop up its currency, the yuan. Despite all its spending, China's total holdings -- by public institutions and private investors -- of U.S. Treasury debt is up a bit from a year ago.

That's also true for the majority of countries: total foreign holdings increased in December compared to a year ago. So even though central banks are dumping U.S. debt, there's plenty of demand for it from private investors.

Related: Central banks are running 'out of ammo'

End of the 'global savings glut'

Commodity prices boomed between 2003 and 2013 fueled by seemingly insatiable demand by China as it built up its cities and its economy. Many commodity-rich countries like Brazil also grew in tandem.

These countries seized the boom as a chance to ramp up their foreign reserves by buying hundreds of billions of debt issued by the U.S. Treasury. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke in 2005 called it the "global savings glut."

After beefing up foreign reserves for a decade, central banks finally started to sell last year. Total foreign reserves hit $12 trillion in 2014 and last year fell to about $11.5 billion, according to IMF data.

Last year, China posted the worst growth in 25 years. Its appetite for commodities softened, causing prices to plummet and leading to a ripple effect on economies and currencies globally.

Central banks are scrambling to prevent their currencies from plummeting even further. The U.S. debt selloff could be a trend for some time, expert say.

"I would expect that we would see this trend continue this year and perhaps into 2017," says Gus Faucher, senior economist at PNC Financial.