If the FBI manages to break into a San Bernardino terrorist's iPhone, there's a tiny possibility it might be forced to tell Apple how it pulled off the hack.

The Obama administration adopted a little-known cybersecurity rule in 2010 called the "vulnerabilities equities process."

The rule kicks in when the government discovers a powerful, never-before-seen hack. Some of the government's top technical minds at the NSA, Secret Service and other agencies must meet with the president's National Security Council to discuss whether or not to share flaws so they can be fixed.

The logic of the rule is simple. The American government tries to spot holes in technology, such as glitches that makes iPhones hackable. Although the government could exploit those bugs to solve crimes and conduct espionage, that same hole can be used by others against the American people.

Keeping those "zero-day" hacks secret is the equivalent of stockpiling weapons that can be used against the U.S. government, companies and individuals. That's why the government considers disclosing zero-days publicly, so tech companies can fix their software holes and make Americans safer. It's a matter of national defense.

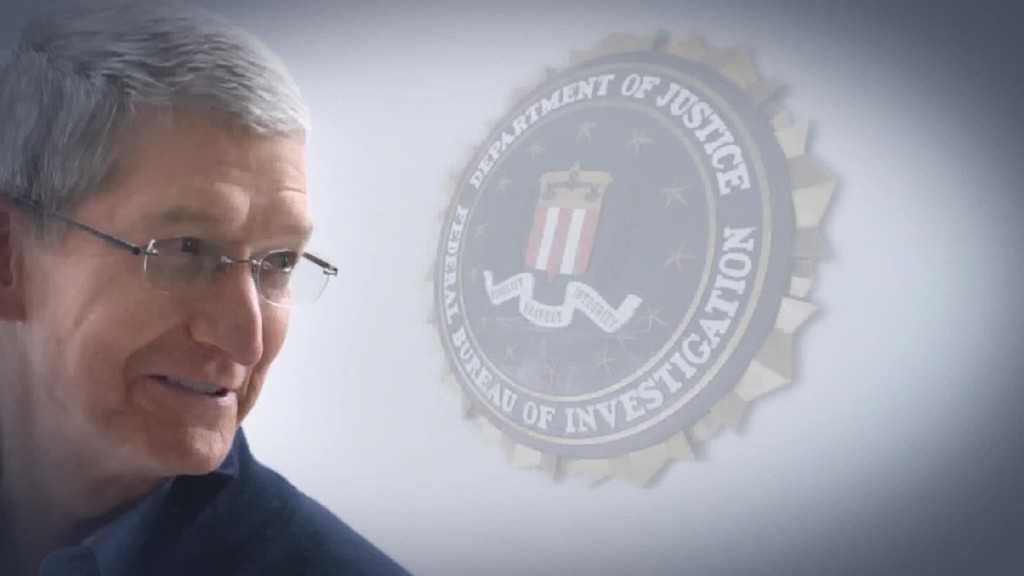

In the San Bernardino case, the FBI says its agents got help from a third-party that might have discovered a way to break into the terrorist's iPhone 5C. If this break-in technique actually works, it means iPhones have a weak point.

According to the vulnerabilities equities process, there needs to be a White House meeting to discuss the pros and cons of tipping off Apple.

There's no exception. Every single vulnerability acquired by the government must be reviewed this way, a senior Obama administration official told CNNMoney.

But it's unlikely that the FBI will actually tell Apple. Skeptics say the government officials typically in attendance at this meeting are at agencies that would rather keep this secret.

"A lot of people think this process is stacked with groups that are predisposed to not releasing a vulnerability, such as the Department of Justice and the NSA," said Ross Schulman. He's a senior policy counsel at the Open Technology Institute, a think tank, and has knowledge of the way these government meetings work.

There's no telling when, if ever, the FBI will disclose how it'll hack Syed Farook's iPhone 5C.

Nearly every other detail of this White House meeting is kept under wraps. So, we don't know how many glitches they find, when they find them, or how many they actually share.

What little we do know about the vulnerabilities equities policy is because the Electronic Frontier Foundation, seeking transparency, sued the NSA and Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

After a legal battle more than a year long, the EFF got a redacted document that vaguely describes the policy.

"We need more transparency over how the policy works. It took a lot for us to know anything about it," said Andrew Crocker, the EFF staff attorney who led the fight.

Christopher Soghoian, a technologist at the American Civil Liberties Union, worries that few glitches are made public, because exceptions for national security "are so large you can drive a truck through them."

It's important to keep in mind that in 2013, a special team of presidential advisers recommended that the government should go public with vulnerabilities "in almost all instances."

But experts still don't expect the FBI to share this one.