All signs are pointing to Cellebrite, an Israeli company, as the mysterious "outside party" that helped agents unlock the iPhone used by the San Bernardino terrorist.

An elite group of engineers at Cellebrite -- led by a "brilliant" hacker in Seattle -- helped the FBI crack the iPhone 5C last week, according to two people with direct contact to the team.

Everyone at the company has since been forced to sign non-disclosure agreements to remain silent about the matter, one of them said.

Additionally, government records now show that Cellebrite landed its biggest contract ever with the FBI -- one worth $218,000 -- the very same day the FBI announced it successfully hacked Syed Farook's iPhone.

And last week, Tel Aviv newspaper Yediot Ahronot, citing anonymous sources, said Cellebrite was the outside party.

But on Friday, two law enforcement officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, told CNN the "outside party" was not Cellebrite.

Cellebrite has declined to comment. Yet the company has benefited from all the speculation. Just after the FBI announced success Monday evening, shares of the Sun Corporation, which owns Cellebrite, jumped 9.8% on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

So, what is Cellebrite exactly?

For years, it has been the go-to resource for FBI agents breaking into suspects' phones, according to security researchers familiar with the FBI's operations.

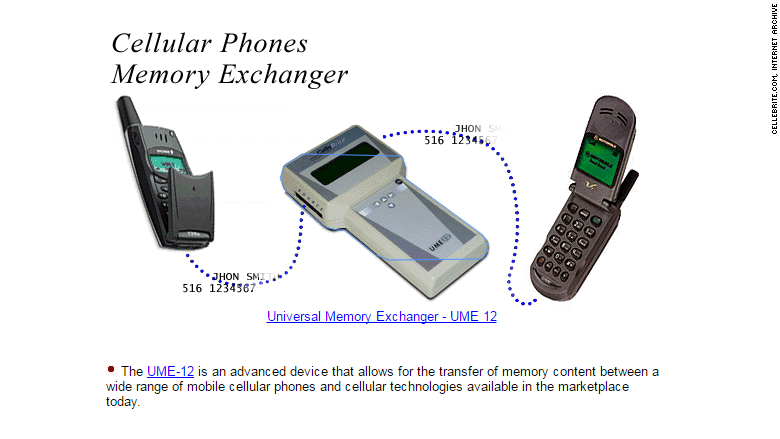

But it didn't start that way. Cellebrite began in 1999 making machines that would easily transfer data from one cell phone to another -- a useful tool for mobile retailers when customers were upgrading to new phones. Cingular, Motorola, MetroPCS, Nokia (NOK) and Verizon (VZ) used Cellebrite's "mobile phone synchronization" to pull out data from broken phones and upload it to new devices.

That expertise in extracting phone memory came in handy.

In early 2007, Cellebrite started marketing its tools for "forensics and law enforcement." At the time, it was able to grab data from "over 1,000 handset models" of mobile phones and PDAs, according to its website.

Its Universal Memory Exchanger -- like the UME-36Pro in 2008 -- could obtain "phone book contacts, SMS messages, pictures, videos, ring tones and audio files... regardless of mobile vendor, model, technology or carrier."

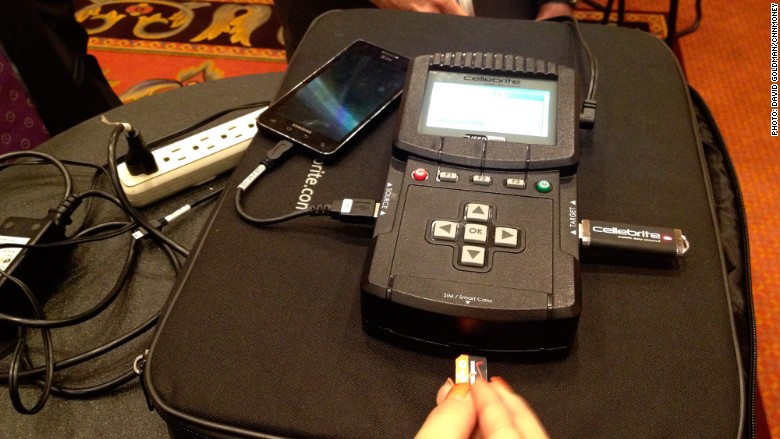

Eventually, law enforcement came to rely on Cellebrite's Universal Forensics Extraction Device, the UFED. It's a small, hand-held device that's easy to use. Police can simply plug in a phone and download the device's memory to a flash drive in a matter of seconds. That's how police can find your deleted text messages.

Now, Cellebrite positions itself as the solution for police when device makers, such as Apple, don't want to help with investigations -- or when the law holds back investigators.

"Uncooperative providers, lengthy legal processes ... make obtaining private and cloud-based data an ongoing challenge," says one Cellebrite brochure. "Our solution uncovers the deep insights needed to accelerate investigations."

Cellebrite advertises these examples: A police officer can pull over a person driving a stolen car, scan his phone and uncover "an even larger city-wide auto theft ring." Or a state trooper can use previously inaccessible data from a suspect's phone to identify a nationwide human trafficking operation.

The Cellebrite UFED Touch Ultimate, a portable version that police can keep in their cruisers, costs $10,000 and works with more than 8,000 electronic devices, according to a product review by SC Magazine.

The tool is so effective that the FBI has signed 187 contracts with Cellebrite over seven years averaging $10,883 a pop, according to government records. Police agencies across the United States have access to this technology as well.

"We allow law enforcement a very deep and detailed access to a lot of information that is on the mobile device," Yuval Ben Moshe, then Cellebrite's forensics technical director, told CNN in 2014.

Early on, passcode-locked phones weren't really a problem for detectives armed with Cellebrite machines. Police were able to bypass locks or crack codes relatively quickly, trying thousands of combinations in seconds.

And even in cases where a passcode presented a real challenge, law enforcement could simply obtain a warrant demanding that Apple or Google help them unlock the phone.

But that changed in 2014, when Apple improved the security of iPhones. Suddenly, there was a class of smartphones that were impervious to police hacking. By November 2015, officers on NYPD's intelligence team told CNNMoney they had indeed become limited in what phones they could access.

Sure, police could still get valuable data -- especially in terrorism cases. The NSA can closely monitor select phone call records. The FBI routinely gets data that customers backup to Apple and Google company servers with iCloud and Google Drive. Emails and app data are usually stored outside the phone at companies that can supply this information to law enforcement.

But police were unable to break into passcode-protected iPhones running iOS 8 or later versions of that software -- and Apple didn't have the keys either.

That's why so many eyes are now on Cellebrite. Many want to know if it figured out how to get past Apple's top-of-the-line security measures this week.

So far, Cellebrite has declined to say.

CNN's Pamela Brown contributed to this story.