America's central bank has two goals: get the country to full employment and keep the costs of goods stable.

The Federal Reserve can put a fat check mark next to those goals. So why is the central bank so hesitant to raise interest rates from almost near zero?

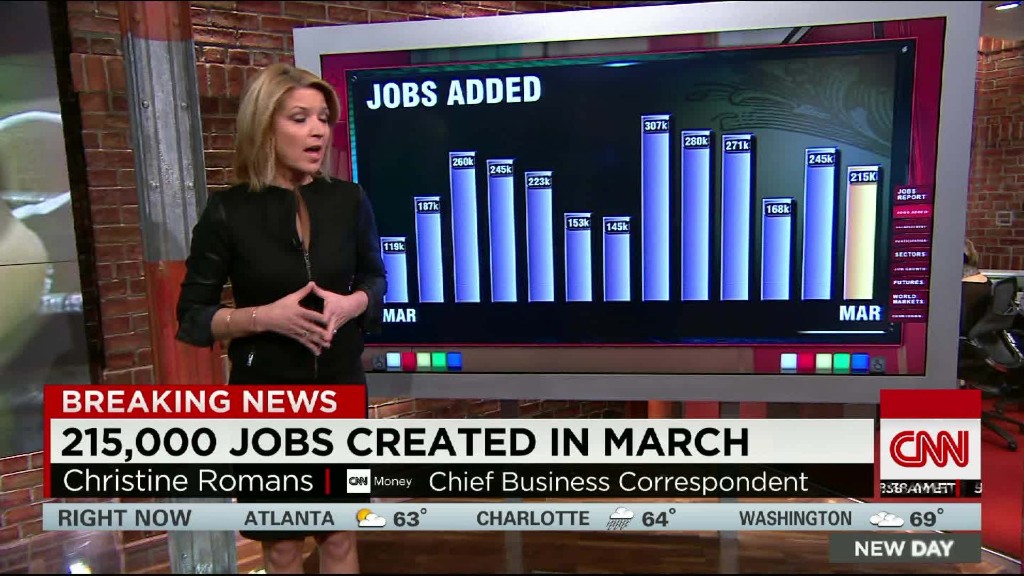

The U.S. is adding jobs at a pace that would leave the new Tesla Model 3 in the dust. March was yet another stellar month of hiring. Unemployment is at 5%, a level many economists consider full strength. Even workers who gave up hope are starting to look for jobs again. That's how positive the jobs picture is.

Inflation isn't quite a home run, but even that is getting close to the goal. The Fed's target for a healthy economy is 2% inflation. The central bank's favorite inflation gauge -- a statistic known as the core Personal Consumption Expenditure index -- is now 1.7%. The other typical measure of inflation (CPI) is also rising.

Still, the Fed hesitates.

Related: U.S. economy gains 215,000 jobs in March

The Fed's missed opportunity

"They're going slow because they missed their opportunity," says John LaVorgna, chief U.S. economist at Deutsche Bank. The Fed could have raised more last year or at the recent March meeting.

Instead, the central bank has become too focused on keeping the stock market happy. It has hesitated so much that even a small move upwards in interest rates has become a big deal.

"The minute the Fed hikes, they get a reaction in the global market that is very destabilizing," says LaVorgna.

That's not how it's supposed to work. A Fed rate hike is supposed to signal good news -- the U.S. economy is doing so well that the central bank feels the need to tap the brakes to ensure healthy growth. But the opposite has happened -- hitting the brakes, ever so lightly, has become a worry sign.

Businesses are on edge. Companies and investors fear the end of the "easy money" days. They don't want the training wheels that were put on during the Great Recession to come off.

Some say the Fed messed up.

The Fed's real worry is...

The Fed didn't raise rates in March. Chair Janet Yellen pretty much told the world this week that an April increase isn't happening either. And the Fed dramatically scaled back its forecast of rate hikes in 2016 from four to only two.

"What this shows is Janet Yellen is just very much a dove. She's just not going to move too quickly," says Joseph Lake, global economist at the Economic Intelligence Unit.

Yellen says she's worried about China (and the global economy) as well as the world markets. She openly admits to them, even though these items are NOT on the Fed's goal list.

Sure, there's some rationale to pay attention to the rest of the world. If China tanks, other parts of the world feel it. It was very apparent last summer when China's slowdown was one of the triggers for recessions in Canada and Brazil, among other nations.

Related: Why Americans are so angry in 2016

But Yellen's concern looks odd now. Fears of a global recession likely peaked in January when the market went into meltdown mode. U.S. stocks slid more than 10%.

But a lot has changed since then. The global economy and oil have mostly stabilized, which is why the U.S. stock market has come charging back and is now positive for 2016.

"It almost looks as if [the global economy] is a bit of an excuse for Yellen and the FOMC. Some of the uncertainty has fallen since January," says Lake.

Even Yellen said this week that the U.S. economy has "proven remarkably resilient" despite the global challenges.

Related: Yellen has killed the strong dollar rally

The Fed doesn't have much firepower left

What's become clear in the past year is that the "Yellen Fed" believes raising rates too soon is far riskier than raising rates too late. When in doubt, she'll opt for going slowly.

But increasingly, experts believe the Fed has created its own cage -- one that's too tied to the market.

On top of that, there's the psychological factor. If the Fed doesn't raise rates until September or December of this year, it's almost like starting at zero again. The angst will likely return about what a rate hike will do to emerging markets and even U.S. consumers if mortgage and credit card rates rise too.

"The longer the business cycle goes, the harder it is for the Fed to hike," says LaVorgna of Deutsche Bank.

Waiting too long could backfire on the Fed if inflation picks up quickly or another crisis hits. Rates are already low and the Fed's balance sheet is still big from all the securities it has already bought up. It doesn't have a lot of "ammo" left to boost the economy.