It began with an early morning phone call and instant fear for the technology director of Horry County, South Carolina's school district.

Computer servers were acting unusual, and Charles Hucks listened as his administrators described frozen computers and a cryptic message spreading across computer screens.

Hucks raced to shut down the system before the unidentified virus could spread, but in minutes, up to 60% of the school district's computers were frozen. Hackers had encrypted the school's data, and that cryptic message was a ransom note.

"They said, 'Hey you want to free your data? Pay us,'" Hucks told CNN.

The school district nestled in the far northeast corner of South Carolina's coast became the latest victim in a crime wave racing across the globe.

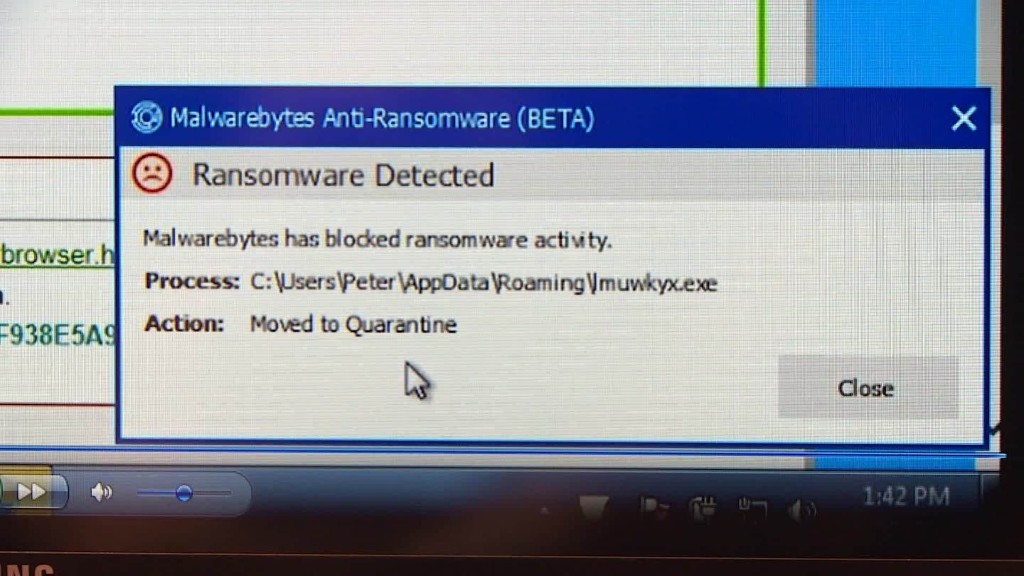

Experts call the crime "ransomware," where criminals lock digital files, like text documents and pictures, and demand a ransom before the system is unlocked.

The FBI says it received 2,453 complaints about ransomware hold-ups last year, costing the victims more than $24 million dollars.

Victims often pay because, so far, authorities like the FBI have been unable to stop it. That was the conclusion made by the Horry County School District.

"You get to the point of making the business decision: Do I make my end-users — in our case teachers and students — wait for weeks and weeks and weeks while we restore servers from backup? Or do we pay the ransom and get the data back online more quickly?"

The hackers demanded to be paid in Bitcoin (XBT), a digital currency that's difficult to trace back to actual people.

Hucks says the district followed the kidnappers directions, bought several bitcoins online, then carefully negotiated a "proof of life" type transaction to make sure the cyberkidnappers would deliver what they promised.

"We chose to send the payment for one machine, first, so that we could ensure that it would work." Hucks says the criminals sent a code for one computer. He entered the code, and the computer returned to operation.

Horry County then deposited the equivalent of $10,000 into the hackers' Bitcoin account and the school computer system was back up and running.

Cybercriminals, many originating in Eastern Europe or the Russian Federation, according to experts, target small- and middle-sized institutions.

Earlier this year, officials at Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital in Los Angeles said they paid the Bitcoin equivalent of $17,000 to cybercriminals after patient and doctor records were locked for almost two weeks. The hospital says it had to resort to handwriting to cope with the computer lockdown.

"It's a very bad trend that has been rising in the past few years," says Adam Kujowa, an expert for the software company Malwarebytes. "It's the one we see people asking for help about the most," he says. "And unfortunately, this isn't the kind of attack that you can get infected and you're done. There's no quick fix."

At a recent cybersecurity conference in San Francisco, dozens of software companies advertised solutions for ransomware but only a few acknowledged success.

That has left many small- to medium-sized companies unable to defend themselves against the attacks, which often enter into computer systems by unwitting employees, according to Paul Roberts, founder of the Internet newsletter Security Ledger.

The ransomware pops up in emails, photos, Internet links and "dozens" of other ways, Roberts says.

"Until we have a kind of global infrastructure to go after these groups making the attacks," he says, "it's going to be very difficult to make these problems go away."

Roberts says he believes the crime is actually much bigger than what the FBI is reporting. That's because companies often pay the ransom and free their data without reporting it.

"Most people aren't talking. Companies don't want their customers, or governments don't want their citizens, to think, they're not protecting their computer systems," Roberts told CNN. "And my guess is this is a much bigger problem than we know about and many of these instances go unreported."

Related: U.S. hospitals are getting hit by hackers

Hucks says the Horry County School District has made a deliberate decision not to hide anything.

"We know of several other districts, some other school districts, where this has happened, and they'd been able to keep it out of the news, which is great for them." But Hucks says it's time to start talking openly about ransomware to warn others and bring attention to a silent crime wave.

"We got hit, the hospital in California got hit. Virtually every day you hear of a virus such as this."