Saudi Arabia is pulling out all the stops to raise cash and fill the hole in its budget created by cheap oil.

It's a huge reversal of fortunes for the Saudis. For years, the kingdom relied on hauling in gobs of oil money to support generous perks to citizens and the kingdom's massive military.

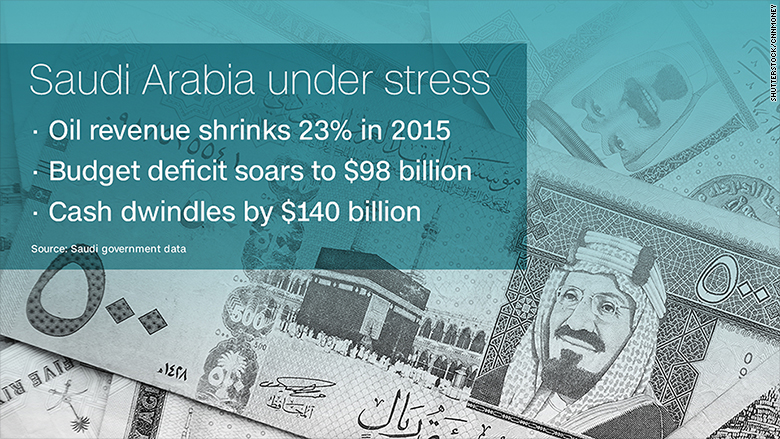

But all that oil money is quickly drying in a world where oil prices have plunged to $40 a barrel from $108 less than two years ago. Saudi oil revenue -- which makes up nearly three-quarters of its total -- plunged 23% last year. The Saudi budget deficit soared to $98 billion last year.

Now the Saudis are desperately trying to replace that oil money with methods that were unthinkable just years ago.

"Saudi Arabia is contending with major economic problems and financial pressure during this era of cheap oil," said Giorgio Cafiero, CEO of Gulf State Analytics.

Related: Saudi Arabia's money ties to the U.S. are massive...and murky

Saudis need a big loan: For the first time in 25 years, Saudi Arabia is in the market for a big foreign loan. The kingdom plans to raise $10 billion from a group of banks that include JPMorgan Chase (JPM) and HSBC (HSBC), according to the Financial Times.

The five-year loan could pave the way for the country to launch its first international bond sale. Last year the Saudis tapped the local bond market for the first time in eight years, raising at least $4 billion.

There is additional pressure on the Saudis given the failure last weekend to reach an agreement to "freeze" oil production at the big summit in Doha. Freezing production would have helped the global oil glut from worsening.

"With the Doha meeting ending in a bust, the pain is set to deepen for the vast majority of sovereign producers," Helima Croft, global head of commodity strategy at Royal Bank of Canada, wrote in a research report.

News of the Saudi loan comes just as President Obama is visiting Saudi Arabia amid rising tensions between the two countries. The Saudis recently threatened to sell off American assets if Congress passes a bill that would allow 9/11 victims to sue foreign governments.

Selling a piece of the crown jewel: Saudi Arabia is even willing to give up a slice of its crown jewel Saudi Aramco. The massive state-owned oil company produces 12% of the world's oil. Aramco is estimated to be worth trillions so even just a small stake sold through an IPO could raise a ton of cash.

Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman wants to list Aramco in Saudi Arabia, possibly as early as next year, in a bid to raise cash.

Related: Saudis to take control of largest U.S. refinery

Burning through cash: The vast treasure of cash amassed at the Saudi central bank during the boom years is fast dwindling. The Saudis burned through about $140 billion between the end of 2014 and February. The central bank is still sitting on $592 billion, but the IMF recently warned that even the Saudis could eventually run out of cash.

That's because the Saudi government, which supports a population of nearly 30 million, is still budgeting for far higher oil prices. The Saudi fiscal breakeven oil price is estimated at just over $100 a barrel, according to RBC. That's the second-highest among all OPEC nations, behind only Venezuela and Libya, two countries in deep turmoil.

By comparison, neighboring countries with far smaller populations like Qatar and Kuwait need oil prices in the $45 to $55 range, according to RBC.

"Saudi Arabia has the most at risk" compared with its Gulf peers, Croft wrote.

Related: Saudi Arabia faces 'economic bomb'

Painful spending cuts: Financial stress caused the Saudis to order a 14% spending cut for 2016. That included a 3.6% decline in military spending, a tough pill to swallow given the enormous security challenges in the Middle East.

The Saudis are also cutting back on some of the lavish government subsidies provided to citizens. That resulted in a 50% hike in gas prices and higher prices for water and electricity.

Croft said the Saudi government "increasingly stands alone" in its conviction that there won't be a public backlash to these austerity moves.

"Once the government starts rescinding benefits...the populace in turn may demand a greater say in how they are governed," she wrote.