Nigerian-born Chidiebere Akusobi has notched many impressive academic achievements in his short life.

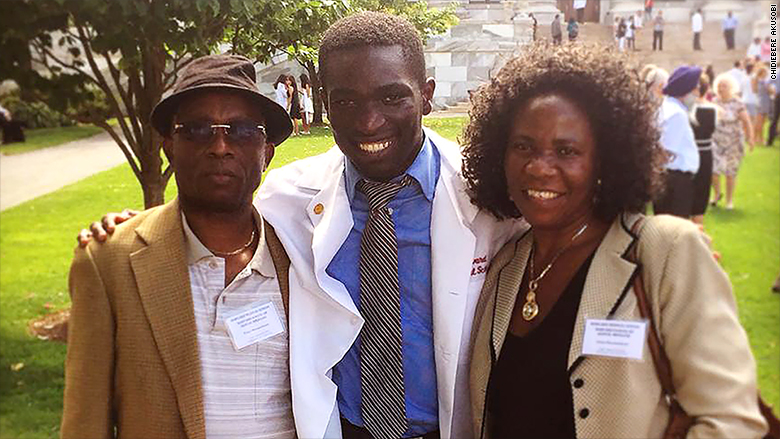

The 25-year old studied ecology and evolutionary biology as an undergraduate at Yale, then earned his master's in biochemistry from the University of Cambridge. Now he's three years into a joint PhD/MD program researching cures for infectious diseases at Harvard and MIT.

But if you ask him, he'll tell you that the biggest academic hurdle he ever had to overcome was in the fifth grade.

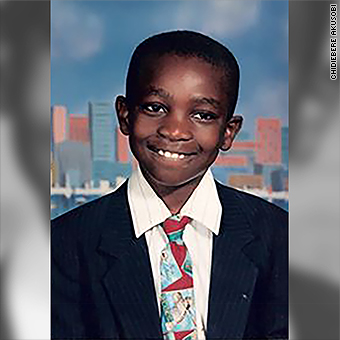

That's when Akusobi, who had moved from Nigeria to the impoverished New York City neighborhood of the South Bronx when he was two years old, was accepted into the rigorous New York City Prep for Prep program.

The program is an educational boot camp that selects roughly 225 promising students a year from the poorest New York City neighborhoods and grooms them for scholarships to attend the city's top private schools.

Related: My American Dream - Fighting for immigrant rights in the Deep South

For 14 months, students were assigned six hours of homework a day -- on top of their normal workload -- and they were expected to read one book a week, he said.

"I remember July 4th, 2001, everyone was outside and there were fireworks. I was inside and my mom was keeping me awake as I read," he said.

But Akusobi was determined to complete the program.

"I was taught that [education] was our shot of the American Dream," he said.

When he was done, he had won a full academic scholarship to Horace Mann, one of the most prestigious prep schools in New York City.

Once Akusobi enrolled, finding his place in the school's rarefied halls became his next big challenge.

Related: My American Dream - Offering legal help to other immigrants

He was only 12 and the stark contrast between he and the other mostly white, wealthy students was striking.

"I realized that there are people that go on vacations every summer or have summer houses or drivers," he said. "It's funny to go to a school where kids have trust funds and then to take the bus home to the South Bronx."

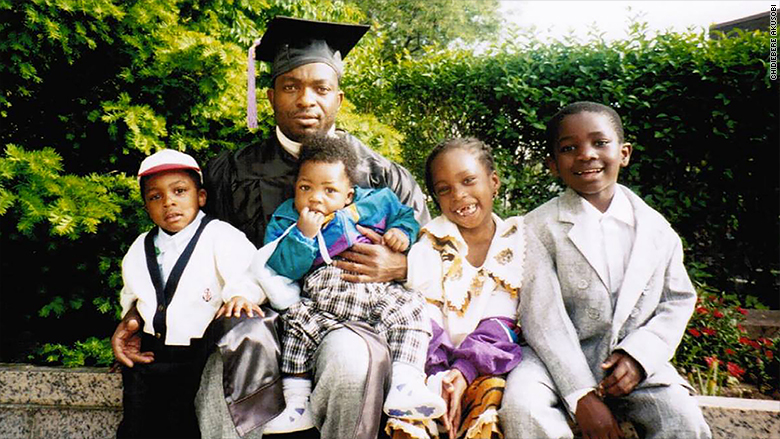

At the time, Akusobi's father was working three jobs while also studying to become a nurse. His mother, who was also pursuing a nursing degree, worked as a home health aide.

"They were working to support me and my three younger siblings. That's the reason they left Nigeria, to provide a better life," he said.

Akusobi took full advantage of what Horace Mann had to offer. He became head of the dance team and even wrote and acted in a one act show.

"I just took advantage of all the opportunities that I could and did well enough that I got into Yale," he said.

But his true passion was medicine.

Related: I want to bring health care to undocumented immigrants

Even though he had left Nigeria at a young age, Akusobi remained close to family members who still live in the country. "When I go to Nigeria there's a sense of being home because that's where my folks grew up," he said.

But the attachments have come with heartache each time he receives news of a family member or friend who has passed away from an infectious disease, like malaria or HIV.

"It's shocking the toll that infectious diseases have. I could work on fixing that. There's real impact that has to be made," he said.

And Akusobi is getting closer to that goal. Recently, he was granted one of the Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowships for New Americans, which will pay up to $90,000 for his joint PhD/MD program at Harvard and MIT.

Besides his research at Harvard/MIT, Akusobi has advocated on a variety of issues, especially those dealing with racial equality and diversity in medicine.

He helped organize the WhiteCoat4BlackLives movement on Harvard Medical School's campus to commemorate Eric Garner and Michael Brown, two black men whose deaths at the hands of the police spurred a national movement against police brutality and highlighted the issue of racism in America.

He has also taken a leadership role at the Student National Medical Association, which seeks to help get more minorities like Akusobi involved in the practice of medicine.

"From what I've seen there are so many students that have potential," he said. "But there is systemic injustice and institutionalized racism that doesn't allow people to get to where they need to be."

Related: Daughter of immigrants challenges the American Dream

While he believes in the American Dream, Akusobi says he realizes it isn't a reality for many people, especially those who didn't get the opportunities he did.

"The American Dream for a lot of people is a fantasy. I have experienced sub par schools with sub par teachers," he said. "An elementary school student attending those schools and living in a neighborhood without quality food or after-school opportunities and surrounded by people in that situation. For a kid in that situation it's easy to see how they might feel like the American Dream doesn't exist."