The green pastures of Dauntley Vale in the west of England offer an unlikely backdrop to a Brexit battle royale.

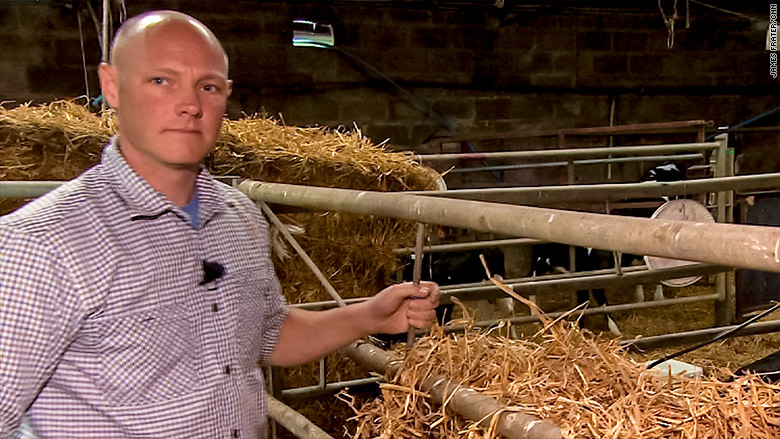

But mention Britain's referendum on whether to remain a member of the European Union in the Cryer household and things get heated.

"If we go out and things get tough, I'll be the one saying I told you so," Ceri warns her husband Chad.

"I still think we could go it alone," he replies, arguing in favor of a vote for Brexit, i.e. to leave the EU. "But I'm not vindictive."

After 10 years of marriage, and three children, the thirty-something couple are used to having to compromise.

But on one issue Chad is unyielding: European bureaucrats have spawned reams of red tape and sown the seeds of unfair competition, he says.

"It's not a level playing field," he says. "Europe isn't under any kind of control. It is expanding and we have no control over that expansion. The only way we will have a say is if we vote to leave."

Related: World leaders: Brexit is a 'serious risk to growth'

Yet Ceri believes that leaving the EU would make it harder for U.K. farmers to sell into a market of 500 million consumers that buys $13 billion of British produce. That could leave them worse off for years to come.

"I think it's an arrogant position to assume Europe will want us just because we are big, consumers will just want cheap food wherever it comes from," she says.

And there's more at stake than future trading relationships.

Brexit could have a big impact on the finances of businesses like the Cryer's family dairy because they could lose EU subsidies which make up half their income.

Farmers have had a love-hate relationship with the EU for more than 50 years since the nascent block introduced the Common Agricultural Policy -- a system which was designed to ensure there was enough food for all in the aftermath of World War Two.

But generous handouts and production quotas ended up distorting the market, creating gluts of some products such as butter, milk and wine.

The grants don't help much in the dairy business, where a collapse in milk prices means many farmers sell their output at a loss.

To make up the difference, Ceri and Chad have had to diversify into cheese, yogurt and ice cream, which command higher margins.

Related: Bloomberg is funding campaign to keep U.K. in Europe

But in a twist of fate, it was a trip to the European Parliament to collect an award for their cheese that caused Chad to go sour on the EU.

"We are all expected to stick to the rules and quotas and the reality is no one does. Italy didn't stick to their milk quota, for instance. None of it is fair," he says.

The farm has been in Ceri's family since 1910. Whichever way the U.K. votes, the impact of the decision will be felt by the next generation -- Ceri and Chad's sons, Bede, Abel and Eric, aged between seven years and six months old.

"I'd like my sons to have the opportunity to keep on farming for years to come," says Ceri. "Within Europe there is a more positive future for farming," she says.

"I think we could go it alone," says Chad, "and I would like the farm to still be here in a hundred years."

What does Bede think of that?

"I want whatever is best for farmers," says the seven year-old... diplomatically.

-- CNNMoney's James Frater contributed to this article.